Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a type of inflammatory arthritis that causes swelling, stiffness, redness, pain, and damage to the skin, nails, joints, and more. PsA occurs because your immune system is overactive, causing inflammation that can affect your joints, skin, and other parts of your body.

It is a chronic, lifelong condition that, if left untreated, can lead to permanent joint damage and deformities. It is important to diagnose psoriatic arthritis early, begin treatment immediately, and work with your rheumatologist and dermatologist to monitor your disease activity along the way and adjust your treatment plan if necessary.

Is psoriatic arthritis progressive? Meaning: Does it get worse over time (particularly without adequate treatment)? For many patients, the answer can be yes, but the course of disease is not always straightforward. Psoriatic arthritis presents differently for different people, making it hard to establish clear-cut stages.

“Psoriatic arthritis is unpredictable,” says Zhanna Mikulik, MD, a rheumatologist and immunologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Some people will have mild disease for many years and go into remission, some will have severe disease early on and require aggressive treatment, she explains.

“The course of the disease seems mostly genetic, but we haven’t yet figured out which factors contribute to worse disease,” says Rebecca Haberman, MD, Clinical Instructor of Rheumatology at NYU Langone Health in New York City

By understanding the signs of psoriatic arthritis and the ways that it can progress, you can make sure that you’re working with your dermatologist, rheumatologist, or other health care providers to get the best treatment to control inflammation, minimize pain, and prevent permanent damage.

Understanding PsA Domains

One of the challenges of psoriatic arthritis is that there are six domains — or general categories of symptoms and areas of the body affected — that may need to be addressed, says Vinicius Domingues, MD, a rheumatologist in Daytona Beach, Florida. These psoriatic arthritis domains include:

- Axial (spine) disease

- Dactylitis (inflammation of a full finger or toe, often called sausage fingers)

- Enthesitis (inflammation of the entheses, where ligaments and tendons connect to bones — a common site is the Achilles tendon in the heel)

- Nail lesions

- Peripheral arthritis (inflammation, pain, and swelling of joints in the hands, arms, feet, legs)

- Skin psoriasis

Not everyone with psoriatic arthritis will experience all domains; they can have unique combinations with different degrees of severity. It’s also impossible to predict who will or will not progress to other domains, says Dr. Haberman.

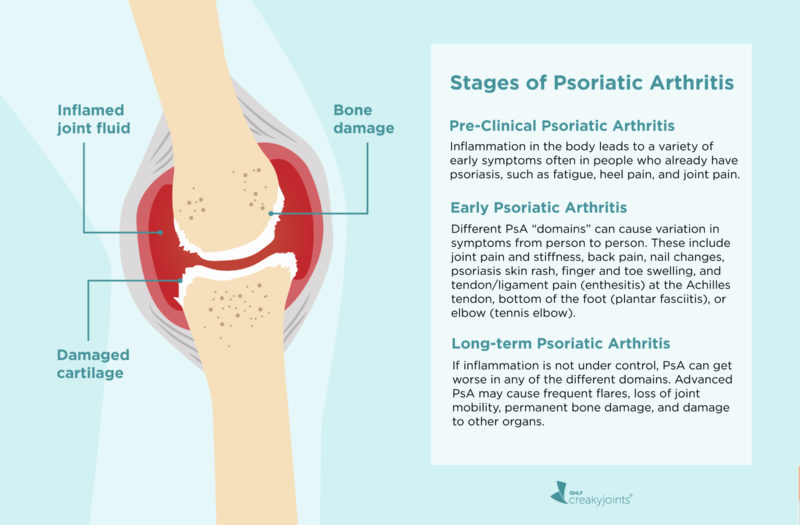

Here is a look at three general phases of psoriatic arthritis and what each one is like.

Pre-clinical Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis doesn’t arrive completely out of nowhere. People who are ultimately diagnosed with PsA can look back and identify symptoms that occurred for months and years beforehand. Much of the time, these symptoms are subtle, mistaken for other health issues, or don’t seem connected to each other — all of which can delay getting a diagnosis.

Doctors and researchers are actively researching what constitutes pre-clinical PsA, or the very earliest symptoms. There is not yet official consensus on what pre-clinical PsA is, says Dr. Haberman, but analyzing people with psoriasis — and observing who goes on to develop PsA and who doesn’t — is starting to provide some clues.

Focusing on People with Psoriasis

Most people with psoriatic arthritis (around three-quarters) have psoriasis first. For a small percentage of patients, psoriatic arthritis occurs before psoriasis, although most often they will have a first-degree relative [sibling or parent] with skin psoriasis, notes Dr. Haberman. Still, others have no skin psoriasis or don’t notice the psoriasis hidden in areas like the scalp, umbilicus, and gluteal fold.

Read more about the connection between psoriasis and PsA.

“Up to 30 percent of patients with psoriasis will go on to develop psoriatic arthritis,” says Dr. Haberman. The majority of cases begin with the skin condition and then progress to joint pain within seven to 10 years. “Recent studies have found that patients with psoriasis who develop severe fatigue, heel pain, and joint pain without overt swelling are more likely to develop PsA.”

While we don’t yet know which individual patients with psoriasis will go onto develop PsA, researchers have identified a few potential risk factors for the progression of PsA, including:

- Family history of psoriatic arthritis

- Psoriasis that affects the scalp and groin

- Nail involvement in psoriasis, such as nail pitting

- Being overweight or obese. “PsA is worse in patients who are overweight and often biologics may not work as effectively in people who are overweight,” says Dr. Haberman.

- Smoking

- Age (between 30 to 50)

- Exposure to certain infections (streptococcal infection, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Physical trauma

If you have psoriasis and any of these factors, it’s important to be aware of the possibility of progressing to PsA and to discuss what signs to watch for with your dermatologist and/or your rheumatologist. Read more here about psoriatic arthritis risk factors.

Early Stages of Psoriatic Arthritis

Recognizing the signs of psoriatic arthritis can be tricky since symptoms differ from patient to patient. For example, one person can experience psoriasis skin involvement and peripheral arthritis, another may experience axial disease (back pain), and someone else could have a combination of all three.

What’s more, especially during early disease, you may confuse your symptoms with other conditions. People can mistake enthesitis, inflammation of the entheses (where a tendon or ligament attaches to the bone) for tennis elbow or dactylitis (“sausage fingers”) for an infection, explains Dr. Mikulik.

“If you have psoriasis and are having pain in your tendon and musculature and you think ‘maybe I’ve been too active lately,’ that may be the first sign of PsA,” says Dr. Haberman. Doctors commonly hear people chalk up their symptoms to overuse, such as getting more exercise than usual or doing work around the house.

If you experience any of the following signs of early psoriatic arthritis (especially if you have the risk factors mentioned above) it’s important to see your doctor as soon as possible:

- Back pain (along the sacroiliac joints, which is where the spine connects with your pelvis)

- Changes in your fingernails or toenails, including holes, pitting, discoloration, or softness

- Eye inflammation (uveitis)

- Fatigue

- Joint redness and swelling

- Morning joint pain that improves with activity

- Psoriatic flares (“When you’re in early disease, however, you may not know the difference between a flare and non-flare; you just feel bad,” says Dr. Domingues.)

- Reduced range of motion

- Sausage-like swelling of an entire finger or toe (dactylitis)

- Scalp psoriasis

- Skin rash (psoriasis plaques on the elbows, knees, and around the ears, scalp)

- Tendon or ligament pain (enthesitis) at the Achilles tendon, bottom of the foot (plantar fasciitis), or elbow (tennis elbow)

Long-Term/Active Psoriatic Arthritis

While PsA may progress differently for each person, worsening of one or more domains likely means the disease has progressed and more aggressive treatment is needed, says Dr. Domingues. For instance, “if a patient is doing well from a skin and peripheral joint perspective, but you have significant back pain and an MRI shows inflammation in the low back, then that indicates the disease has progressed.”

Other signs of disease progression include:

More constant flares

“A one-off flare is never meaningless but in the context of being in remission, it is acceptable,” says Dr. Domingues. “But if you’re having flares every couple of months, and needing steroids, then [your PsA is active] and you likely need a switch in your baseline therapy.” Flares can happen at any point of the disease, adds Dr. Haberman, but it does mean that you are actively inflamed and there is a possibility that you will develop joint damage.

Loss of significant joint mobility

For example, you were able to flex your wrist 60 degrees, and two years later, you lost 50 percent of that range of motion. “It’s possible to feel okay and still experience loss of range of motion, says Dr. Domingues. “But the idea is to prevent joint damage and to make you have less pain. If you have less pain and are still progressing, that means your treatment could be working better.”

Permanent bone damage

Bone erosion, or loss of bone, which occurs from extended periods of inflammation, and new bone formations (enthesophytes), which occur where tendons attach to bones, are both signs of psoriatic arthritis progression. They can typically be observed on an X-ray. “Once you get to this point, you can experience limited mobility and pain related to this damage that can’t be treated with medications,” says Dr. Haberman, although future damage could be prevented.

Other inflammatory diseases

In addition to joint damage, the inflammation of PsA can cause damage to other organs of the body, including your heart (cardiovascular disease), eyes (uveitis), and the inner ear (hearing loss).

Understanding Remission and Minimal Disease Activity

Psoriatic arthritis disease progression is not inevitable. When your PsA is treated with medications that reduce immune system overactivity, you can reduce your disease activity to a point that it’s no longer causing significant symptoms or increasing the risk of long-term health issues.

In general, going into remission means that you are no longer showing signs of active disease. Decades ago, remission wasn’t conceivable for most people with psoriatic arthritis, but thanks to a proliferation in medication treatment options, getting to remission is a possibility for PsA patients today.

However, going into remission does not mean that you will stay there indefinitely. It is common for PsA symptoms to wax and wane. “Even if you’ve been in remission for a long time and your pain starts coming back and you start flaring more, you may need to change your medication for better control,” says Dr. Haberman.

You may also hear the phrase “minimal disease activity” in conjunction with psoriatic arthritis and remission.

Doctors don’t have a clear definition of what it means to be in remission in PsA, but they have defined something called minimal disease activity as a treatment “target.” This is what your doctor may use to determine whether your PsA disease activity is low enough that you have few symptoms and a low risk of long-term damage.

To determine whether you are in minimal disease activity, your rheumatologist or dermatologist will likely use the following tests and scores along with a physical exam to check for skin psoriasis and joint mobility:

- Number of tender joints

- Number of swollen joints

- A psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score

- Your own assessment of pain

- Your own assessment of disease activity

- Your own assessment of everyday function and disability

- Number of points of enthesitis

People are considered to be in minimal disease activity when their scores on five out of these seven criteria are low enough.

“A combination of all of these will determine minimal disease activity or remission and whether the patient is happy with how they are doing,” says Dr. Haberman. “We also have to take into consideration a patient’s health goals and priorities.”

Even if you are never able to reach minimal disease activity or remission, it is important to work with your health care team to manage your symptoms and lower disease activity so inflammation from PsA does not harm your joints or organs or impact your quality of life.

How Psoriatic Arthritis Treatment Prevents Disease Progression

The primary way to slow the progression of PsA is through medications that modify the immune system. It may take trial and error to find the treatment that works best for a given patient, notes Dr. Haberman. “While we have a lot of medication options for PsA, we don’t know which ones a patient will respond to, so sometimes we need to try more than one medication to find the one that’s right for that patient,” she says.

In addition, medications that have been effective for you can stop working over time. If this happens, your doctor may recommend a medication that works differently — say, targets a different part of the immune system — to control disease activity.

There are many drugs used to treat PsA. The ones that you will use will depend on the type and severity of symptoms as well as the most problematic areas (or domains).

Medications use to treat PsA include:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

These medications, such as ibuprofen or naproxen or prescription versions, are used to treat mild joint pain but not skin psoriasis or nail involvement; they don’t prevent disease progression.

Glucocorticoids

These medications, such as prednisone, help reduce inflammation quickly and tend to be prescribed during flares. They used sparingly and carefully in people with PsA because they can have a wide range of side effects.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

These medications address the underlying systemic inflammation in psoriatic arthritis. They are critical for slowing and stopping the course of inflammatory disease and can treat both skin and joint pain at the same time. They fall into three general categories.

- Conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which are often taken orally and include medication such as methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine

- Targeted disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which are oral pills that are more targeted than conventional DMARDs [ex: a JAK inhibitor like tofacitinib (Xeljanz) or a PDE4 inhibitor like apremilast (Otezla)]

- Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which are administered as injections or infusions and are more targeted than conventional DMARDs [ex: a TNF inhibitor like adalimumab (Humira) or etanercept (Enbrel), an IL-17 inhibitor like ixekizumab (Taltz), an IL-23 inhibitor like guselkumab (Tremfya) or a T-cell inhibitor like abatacept (Orencia)]

“Over the last 20 years we have completely revolutionized the field and have phenomenal treatment for psoriatic arthritis,” says Dr. Domingues. “Our expectations for results need to be very high because we can help people feel great.”

Audio Guide: Understanding Psoriatic Arthritis Treatment

Learn more about the medication treatment options available for psoriatic arthritis. For more audio guides and insights from PsA experts, check out the Psoriatic Arthritis Club podcast.

If you enjoyed reading this article, you’ll love what our video has to offer.

Behrens F, et al. Minimal disease activity is a stable measure of therapeutic response in psoriatic arthritis patients receiving treatment with adalimumab. Rheumatology. November 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key203.

Busse K, et al. Which Psoriasis Patients Develop Psoriatic Arthritis? Psoriasis Forum. Winter 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4206220.

Coates LC, et al. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. January 2010. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.2008.102053.

Haberman R, et al. A Delphi Consensus Study to Standardize Terminology for the Pre-clinical Phase of Psoriatic Arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis & Rheumatology. November 2020. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/a-delphi-consensus-study-to-standardize-terminology-for-the-pre-clinical-phase-of-psoriatic-arthritis.

Interview with Rebecca Haberman, MD, Clinical Instructor of Rheumatology at NYU Langone Health in New York City

Interview with Vinicius Domingues, MD, a rheumatologist in Daytona Beach, Florida

Interview with Zhanna Mikulik, MD, a rheumatologist and immunologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Ogdie A, et al. Comprehensive Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis: Managing Comorbidities and Extraarticular Manifestations. The Journal of Rheumatology. November 2014. doi: https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140882.

Patient Education: Psoriatic Arthritis (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/psoriatic-arthritis-beyond-the-basics.

Saber TP, et al. Is Remission a More Realistic Goal in Psoriatic Arthritis? Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. January 2011. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X10389847.

Wervers K, et al. Time to minimal disease activity in relation to quality of life, productivity, and radiographic damage 1 year after diagnosis in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. January 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1811-4.