It might seem impossible to think about exercising with arthritis, especially on days when you can barely think about getting out of bed. Plus, you may think that exercise will aggravate your arthritis and cause flare-ups of stiff, painful joints.

But it’s just the opposite. Staying active is a mainstay for managing most types of arthritis, whether you live with a wear-and-tear type like osteoarthritis or an inflammatory type like psoriatic or rheumatoid arthritis, or even a chronic pain condition like fibromyalgia. “Lack of exercise can cause arthritic joints to become more stiff and painful,” says Kelyssa Hall, CSCS, CES, an exercise physiologist at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. “People [with arthritis] who avoid exercise are setting themselves up for more discomfort and possible injury down the road.”

Luckily, there are ways to make exercising with arthritis easier, especially on days when your joints are a little stiffer and you’re a little more fatigued than usual. You don’t even have to spend hours at the gym; just make an effort to get up and move, says Alexis Ogdie, MD, Director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic in Philadelphia and Associate Professor of Medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. “It’s like climbing a fence,” she says. “It’s often hard to get started, and tends to get easier once you’re on the other side.”

Benefits of Exercising with Arthritis

Before you start working out, it may be motivating to know the benefits of exercising with arthritis — and there are plenty:

- Stronger bones: “Maintaining bone strength is important in preventing weaknesses in the body that can lead to falls and possible fractures,” says Hall.

- Stronger muscles: “When you’re exercising, you’re retraining the muscles and strengthening the muscles around the joints,” says Dr. Ogdie. “The stronger the muscles are around the joints, the less extra micromotion is going on, so the less pain there will be down the road.”

- Better posture: Exercise promotes good posture, which helps reduce the amount of strain on your spine.

- Less muscle imbalance: Having arthritis in one part your body can cause a muscle imbalance in another part of your body, which causes pain. “Exercise helps figure out where the deficits are and how to get the muscle strengthened and loosened again so there’s less discomfort,” says Dr. Ogdie.

- Cardiovascular improvements: People with inflammatory arthritis have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease because of the inflammation involved in the disease. Aerobic exercise can help rev up and strengthen your heart.

- Decreased fatigue: A 2018 study published in the journal Arthritis Care and Research found that exercise can help fight fatigue in a number of different ways, including reducing inflammation, increasing endorphins, preventing deconditioning, and improving sleep.

- Weight management: Exercise can make it easier to lose weight and reduce additional stress on your joints, but Dr. Ogdie emphasizes that it’s not the be-all and end-all maintaining your weight. A healthy diet is important, too.

- Improved mental health: Exercise has been linked to reduced anxiety and depression in patients with arthritis, says Dr. Ogdie. This has been especially beneficial during the pandemic. A November 2020 study published in the journal Rheumatology International found that people with rheumatoid arthritis who exercised regularly during the pandemic experienced fewer depressive symptoms than those who didn’t.

When and When Not to Exercise

A big part of figuring out how to exercise with arthritis is knowing when to get moving and when to take a rest. Although every person’s situation is different, here are some general recommendations to consider:

- Wake up and go. Dr. Ogdie says that her patients who are dog owners often say their morning stiffness is gone by the time they get back from their morning walk. “Exercise speeds up the resolution of the morning stiffness,” she says. “I know it’s hard if you’re having trouble rolling over or getting down the steps, but the more you get walking and moving, the better you’ll feel.”

- Listen to your body. There are circumstances when you should not exercise at all, says Hall. For example, if your pain persists for more than an hour or if you’re experiencing joint inflammation and unusual fatigue.

- Don’t overdo it. “It is very important to not over-exercise because too much repetitive stress on the joints and muscles can cause flare-ups of arthritis symptoms,” says Hall. “Over-exercising can cause the muscles to be overly fatigued and less supportive to the joints resulting in more wear and tear.” Following the tips below may help ensure you don’t over-exercise.

- Avoid late-night workouts. Try not to exercise too close to bedtime to avoid interrupting sleep patterns, says Hall.

Pre-Workout Tips

Before starting a workout program, it’s best to talk to your doctor about your capabilities and which types of physical activity are best for your body, preferences, and lifestyle. Here are a few more pre-workout tips to keep in mind:

Consult with an exercise physiologist or physical therapist to ensure appropriate programming and proper form of a new exercise routine. “A physical therapist can help you start an exercise program, even if you only go once,” says Dr. Ogdie, noting that many of her patients are concerned about steep copays.

Consider signing up for a personal training session. A small 2020 study published in the journal Clinical Rheumatology found that people who were provided with a safe, structured, and personalized exercise program were more likely to have decreased fatigue, lower levels of C-reactive protein (an inflammatory marker), less excess weight around the midsection, and greater cognitive function than those who were not.

Purchase appropriate footwear that provides adequate arch and ankle support and shock absorption to minimize the forces on the joints. Keep in mind that feet tend to swell during the day, so try on shoes in the afternoon or evening when your feet are their largest.

Invest in comfortable workout wear that is not too restrictive and allows you to move through a comfortable range of motion in a variety of positions, says Hall.

Apply heat to your joints affected by arthritis before a workout to ease pain and stiffness and improve circulation to the muscles and joints.

Allow 10-15 minutes for an active warm-up to prepare the muscles for increased activity. “Pre-exercise stretching can be done after about five minutes into the warm-up and should include stretches that focus on several different muscles including the hamstrings, quadriceps, calves, glutes, torso, chest, and shoulders,” says Hall.

Consider investing in an activity tracker (like a pedometer, Fitbit, or Apple Watch), which can help motivate you to move more, says Dr. Ogdie. A 2018 study published in the journal Arthritis Care & Research found that people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases who used activity trackers took an average of 1,520 more steps per day than those who didn’t use the wearable devices.

Make it as easy as possible to commit to exercise. “Find something that you enjoy doing and something that you’re willing to commit to,” says Dr. Ogdie. “Write it down, lay out your clothes, set your alarm, and tell someone you’re going to exercise.”

Workout Tips

Cardio

A good cardio session has a wide range of both physical and mental health benefits, including less stiffness, fatigue, anxiety, and depression, and better range of motion, improved endurance, and more energy. Good low-impact options include walking, water exercise, swimming, and bicycling.

Take it slow and steady. Start with short bouts of cardio and gradually increase your time if you’re not experiencing any issues. For example, if you’re walking for five minutes and feel tired, try to stick with five minutes each day for a week — and then progress to 10 minutes the next week, 15 minutes the next, and slowly push yourself further, says Dr. Ogdie.

Wet your feet, literally. If you’re new to exercise, water exercise is likely your best bet, especially if you’re starting in a therapy pool with warm water. According to a 2017 study published in the American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, women with RA who did water-based exercises saw significant improvements in disease activity, pain, and functional capacity compared to those who did land-based exercises.

Think variety. “If you exercise three times per week, you might think about walking one day, biking another day, and walking with a little bit of yoga on the next day,” says Dr. Ogdie. Switching things up can help prevent you from overtraining a particular area as well as help you decipher whether your joint pain is related to your exercise or your arthritis, she adds.

Pay attention to your set-up. Biking, for example, is a great cardio workout and relatively easy on the knees, but you need to set up the equipment correctly. Make sure that your knees aren’t over-flexing on your bike, says Dr. Ogdie.

Talk to your doctor about HIIT. HITT, or high-intensity interval training, has been found to improve fatigue in patients with psoriatic arthritis, axSpA, and RA, says Dr. Ogdie. One small study published in Arthritis Research & Therapy found that 10 weeks of a HITT walking program resulted in a 38 percent decline in disease activity for patients with RA, including tender, swollen joints. HITT won’t be right for everyone, of course. This kind of workout is likely a better fit for people with arthritis who are already physically active and aware of their limitations.

Strength Training

Strength training is crucial for increasing muscle mass to help support the joints. A few arthritis-friendly options include bodyweight exercises, weight machines, small free weights, and resistance bands.

Choose the right weights, and build gradually. Hall recommends choosing a load that allows you to perform three sets of eight to 15 repetitions with proper form at a slow controlled pace, and with a rest in between sets.

Make it challenging, but not too challenging. Aim for a seven or eight on an intensity scale of one to 10 (with one being minimal effort). “This is as long as you are not experiencing pain or discomfort with the effort,” says Hall.

Choose movements that involve more than one joint. Hall suggests squats or sit-to-stands, rows, steps-ups, side stepping with a band, presses, and marching. Multi-joint exercises significantly reduce your risk of injury by engaging various muscle groups at once to create a balanced, safe workout.

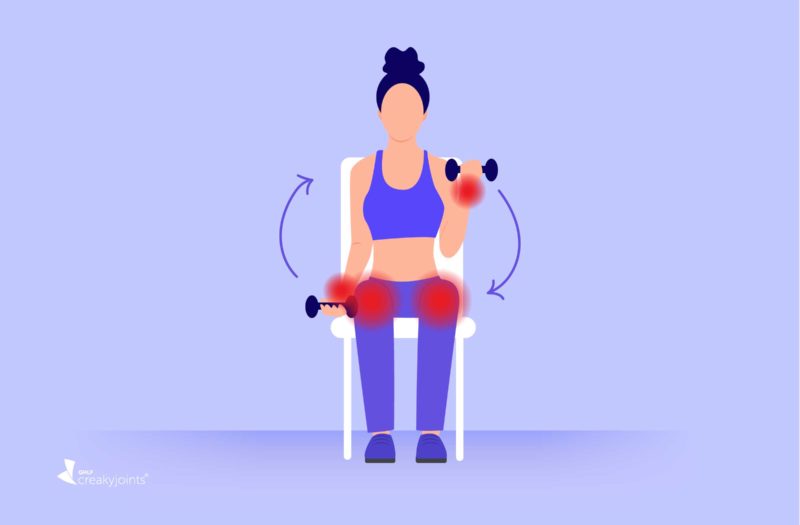

Stay seated. Sitting in a chair when doing arm or shoulder exercises can help to keep pressure off the leg muscles and joints.

Pick arthritis-friendly equipment. Wrist weights can be helpful in minimizing stress on arthritic hands, but make sure you fit them properly. “You don’t want them to be loose and flopping around, and you don’t want them to be too tight either,” says Hall. Exercise bands are also a good choice for upper body exercises, and can also be placed around the ankles or knees “to help make a low-impact exercise more challenging without overstressing the joints,” Hall says.

Flexibility Training

Flexibility training can help you manage your arthritis pain and improve your range of motion. A few arthritis-friendly options include foam rolling, static stretching, yoga, and tai chi.

Never force a stretch or movement pattern. You may feel some mild tension, but there shouldn’t be any pain. “Always move through a comfortable and pain-free range of motion during all exercises and mobility work,” says Hall.

Double-up your yoga mat, or place folded towels or blankets on the floor or under your body for a softer surface when kneeling or doing floor exercises.

Stay seated. You can try chair yoga, or other stretches from the floor so you don’t have to get up and down. For example, Hall says you can do a seated hamstring stretch by sitting in a chair and extending one leg out in front with the knee straight and with the heel on the floor. Next, gently lean forward until you feel a gentle stretch in the back of the knee and thigh area. Make sure you keep your back straight while bending through the hips.

Set yourself up for safety. If you decide to do floor exercises, make sure there is a chair or ottoman nearby to help support you as you get up, Hall says.

Post-Workout Tips

Taking steps to cool down and care for your joints after a workout can prevent inflammation, decrease next-day soreness, and minimize the risk of injury.

Apply cold packs to help prevent inflammation and sooth joints after a workout, says Hall.

Allow time to stretch at the end of your workout. “The more walking you do, the more pressure you put on one particular area like the IT band and the outside of the hip (trochanteric bursa),” says Dr. Ogdie. “This can lead to hip pain, which can be prevented by stretching after walking.”

Have patience. Don’t expect results overnight; it can take six to eight weeks to feel the effects, says Dr. Ogdie.

Want to Contribute to Arthritis Research? Here’s a Simple Way

If you are diagnosed with arthritis or another musculoskeletal condition, we encourage you to participate in future studies by joining CreakyJoints’ patient research registry, ArthritisPower. ArthritisPower is the first-ever patient-led, patient-centered research registry for joint, bone, and inflammatory skin conditions. Learn more and sign up here.

Azeez M, et al. Benefits of exercise in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial of a patient-specific exercise programme. Clininical Rheumatology. February 8, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-04937-4.

Bartlett DB, et al. Ten weeks of high-intensity interval walk training is associated with reduced disease activity and improved innate immune function in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Arthritis Research and Therapy. June 14, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1624-x.

Brady SM, et al. Different types of physical activity are positively associated with indicators of mental health and psychological wellbeing in rheumatoid arthritis during COVID-19. Rheumatology International. November 30, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04751-w.

Davergne T, et al. Use of wearable activity trackers to improve physical activity behavior in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arthritis Care and Research. September 17, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23752.

Interview with Alexis Ogdie-Beatty, MD, MSCE, Director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic in Philadelphia and Associate Professor of Medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Interview with Kelyssa Hall, CSCS, CES, an exercise physiologist at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City

Kelley GA, et al. Aerobic exercise and fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis participants: a meta‐analysis using the minimal important difference approach. Arthritis Care and Research. April 2, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23570.

Siqueira US, et al. Effectiveness of Aquatic Exercises in Women With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized, Controlled, 16-Week Intervention-The HydRA Trial. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. March 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000564.

Thomsen RS, et al. Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Disease Activity and Disease in Patients With Psoriatic Arthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care and Research. June 8, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23614.