Giant cell arteritis (GCA), or temporal arteritis, is not a well-known disease. But it’s more common than you might think: GCA is the most common form of vasculitis (blood vessel inflammation) in adults, according to the Johns Hopkins Vaculitis Center. But it’s easy to mistake GCA for other conditions, such as headache, migraine, or even stroke, because its primary symptoms include severe headaches, tenderness around the temples or scalp, and vision problems.

“Most of my patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA) had never heard of GCA before they were diagnosed,” says Sarah Mackie, a rheumatologist in Leeds, UK, and a founding member of the UK TARGET Consortium, which promotes research and innovation in giant cell arteritis. She worries that patients who don’t know about GCA may put off visiting the doctor because they don’t understand how serious their symptoms could get. What’s more, “the lack of general awareness about GCA and its treatment means that patients can feel isolated, especially if their family and friends also have never heard of this condition.”

The good news is that once GCA is properly diagnosed, it is highly treatable and manageable. But without treatment, it can lead to serious complications, including permanent vision damage.

What Is Giant Cell Arteritis?

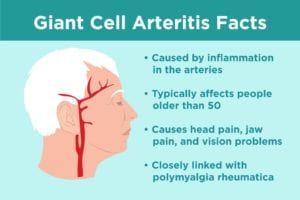

Giant cell arteritis — also called temporal arteritis or cranial arteritis — is a disorder in which the lining of the large blood vessels in your head, and sometimes other parts of the body, become inflamed, which can narrow or completely block the affected arteries, compromising blood flow.

Giant cell arteritis is so named because when you look at biopsies of inflamed temporal arteries (those on the side of your head in front of your ears) under a microscope, you can see large or “giant” cells.

GCA occurs in older adults, usually in people over the age of 50. It’s most common between the ages of 70 and 80 (74 is the average age of onset, according to the Vasculitis Foundation). GCA is more common in women than in men (though some research indicates men are more likely to experience serious eye involvement) and mostly affects people of Northern European ancestry.

The more you know about giant cell arteritis — including recognizing its symptoms and understanding how it is treated — the better position you’ll be in to get prompt medical help and manage your condition.

Symptoms of Giant Cell Arteritis

GCA is one of those conditions where — except in unusual cases — no single symptom is enough to make the diagnosis. As a result, this disease can elude patients and stump physicians, making the road to a GCA diagnosis a tricky one.

“Almost all the GCA symptoms by themselves are non-specific, which means they are also very common in other conditions, or even in the general population,” says Dr. Mackie. “Headache, for example, is extremely common, as most of us get headaches from time to time.”

Giant cell arteritis symptoms include:

Headache

In cases of GCA, the type of headache you might experience is severe and usually concentrated around the temples. It may come and go or get worse over time.

Tender scalp

In addition to headache, your scalp may feel tender. It may hurt to comb or style your hair.

Jaw pain

You may notice pain in your jaw or tongue when you chew. This is called jaw claudication.

Vision problems

GCA can also affect your eyes, causing you to experience double vision or temporary loss of vision. Some people may even permanently lose vision in one eye.

Pain in shoulders and hips

GCA is closely connected to another disease called polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), which is known for causing pain, particularly in the shoulders, neck, and hips. Up to 5 to 15 percent of people with polymyalgia rheumatica will also get GCA — and about 50 percent of GCA patients also have PMR, according to the American College of Rheumatology. PMR is a common reason for new-onset muscle and joint pain in older adults.

GCA can cause a number of other non-specific symptoms, including:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Problems with dizziness or balance

- More rarely, other odd symptoms like sore throat or chest pain

“It is the particular combination of symptoms or features that leads physicians to suspect the diagnosis and to order further tests in order to confirm the diagnosis,” Dr. Mackie says.

And this combination can take its toll on patients. “GCA presents patients with considerable ongoing physical and psychological symptoms that affect their everyday lives in a wide variety of ways,” concluded a 2017 paper in the journal BMJ Open that Dr. Mackie co-authored. The authors suggest that clinicians who understand how GCA impacts their patients’ lives will be able to design better treatment plans that promote a greater sense of independence and normality.

Causes of Giant Cell Arteritis

While there’s a great deal of guesswork regarding the causes of GCA, it is generally believed to be an inflammatory disorder that impacts blood vessels, such as the temporal arteries. When you take a sample of a temporal artery affected by GCA and look at it under a microscope, you see that the artery’s wall is filled with white blood cells, which indicates an immune response.

“Sometimes these white blood cells fuse together to make slightly bigger cells called ‘giant cells,’ hence the name of the condition,” Dr. Mackie says. Inflammation causes the blood vessel walls to become thick, restricting blood flow to certain areas of the head, which contributes to GCA symptoms, like pain, she explains.

As for risk factors, chief among them is age, with the condition most commonly being diagnosed among people in their 70’s. “Whether this is due to aging of the immune system or aging of the artery wall, or both, we do not know,” Dr. Mackie says.

In addition, GCA more commonly appears in people of white Northern European ancestry because this group is more likely to have a particular variant in the genetics that determine how the immune system works.

How Giant Cell Arteritis Is Diagnosed

You doctor will start by asking you to describe your symptoms, and will listen for red flags like headache, tenderness in the scalp, and aching in the jaw or tongue when chewing. Your doctor will also do a physical exam, during which they’ll be on the lookout for swelling or tenderness of the temporal artery, which may sometimes appear lumpy.

If the signs point to a GCA diagnosis, the next step is a biopsy of the temporal artery. You will be given a local anesthetic, and a small sample of the blood vessel will be removed to be examined under a microscope by a pathologist, who will look for white blood cells in the artery wall. Your doctor may also order an ultrasound of the temporal artery to help confirm the diagnosis.

But not every case of GCA is easily diagnosed. “There may be none of these features; some patients present with weight loss, anemia, or a fever,” Dr. Mackie says, adding that such patients are sometimes sent for tests to look for cancer, at which point features of GCA may show up unexpectedly on a PET scan. “No medical test is perfect, and this can lead to further uncertainty,” she says.

Indeed, a 2017 study in BMC Medicine found that, “On average, patients experience a nine-week delay between the onset of their symptoms and receiving a diagnosis of GCA. Even when the patient has a ‘classical’ cranial presentation, delay remains considerable.”

But there is one certainty when it comes to diagnosing GCA: It’s always better to catch it early. For one thing, the sooner you’re diagnosed, the sooner treatment can provide relief of painful symptoms.

For another, GCA could lead to worsening problems if not managed promptly. “Unless it is treated, GCA can sometimes cause loss of vision in one eye, or occasionally both eyes,” says Dr. Mackie. “Although most patients with GCA will never lose their vision, the potential consequences of possible GCA-related visual loss are so profound that often the treatment may be started even before all the tests have been completed.”

Treatments for Giant Cell Arteritis

Corticosteroids

The good news is GCA symptoms typically respond very quickly to treatment with a high dose of corticosteroids (such as prednisone). “This can feel quite miraculous for a patient who has not been able to sleep properly or even comb their hair or chew their food for several weeks or more,” Dr. Mackie says.

Steroids are most often given as tablets, but in cases where the treatment needs to be given rapidly, the first doses may be intravenous. Over time, the steroid dosage is slowly tapered, but if a lowered dose allows symptoms to return, the dosage may have to be increased again. “Ultimately most patients with GCA are able to stop their steroids,” Dr. Mackie says. “The total duration of treatment may be anything between less than a year to five years or more.”

The steroids themselves may have an impact on patients — both positive and negative. “High-dose steroids can cause a burst of energy and euphoria in the first week or two. For other people, being on high-dose steroids is not such a good experience, as the medication can interfere with sleep,” Dr. Mackie says.

While steroids have been used for decades as the primary GCA treatment, they have a number of drawbacks, including side effects that may come with long-term use, such as weight gain, mood swings, susceptibility to infection, and increased risk of osteoporosis and diabetes. Steroids when used long-term should not be stopped suddenly as this can be dangerous.

Steroids suppress the inflammation that GCA causes, but they don’t address treating the underlying condition itself.

Methotrexate

Sometimes low-dose methotrexate — given as tablets or injections — is added alongside steroid treatment for GCA. At these low doses, methotrexate is a safe drug as long as it is prescribed properly and monitored with regular blood tests. (Read more about monitoring methotrexate here.) Methotrexate works in a different way from steroids to suppress inflammation; according to latest thinking, methotrexate seems to boost the action of adenosine, a messenger-molecule the body produces naturally to help calm inflammation.

Used as a first-line disease-modifying drug for rheumatoid arthritis and some other kinds of inflammatory arthritis, methotrexate is intended to reduce steroid dependency in GCA patients. However due to lack of large-scale trials, and doctors still do not know which GCA patients will benefit most from adding this drug.

“There seems to be both hope and uncertainty regarding the use of weekly methotrexate in giant cell arteritis (GCA) patients who need to limit their glucocorticoid use,” according to rheumatologist Jack Cush, MD, in an article on MedPage Today. “While well done clinical trials have shown no certain efficacy, data suggesting methotrexate benefits come from small trials, anecdotal experience, and clinical experience.”

Biologic drugs

Another newer treatment approach for GCA has been the addition of biologic drugs, many of which are already in widespread clinical use for other inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis. “Biologic” means that the drug is made in the laboratory to mimic large proteins made by the body, such as antibodies that are capable of recognizing very specific immune system targets. Some biologics, like TNF inhibitors, did not seem to work well for GCA in preliminary clinical trials.

However, following an international clinical trial published in The Lancet in 2016, tocilizumab (Actemra), a biologic drug that blocks an immune system protein called interleukin-6, is now FDA-approved for treating GCA, the first FDA-approved drug specifically for this type of vasculitis. Tocilizumab is given by injection and requires regular blood monitoring.

“It is a very exciting time for the development of new GCA therapies,” says Dr. Mackie, who notes that many clinical trials for GCA are currently in progress. “Researchers hope this new research will help develop better treatment options for patients with GCA so that they can be safely treated without the side-effects of long-term steroid use.”