My first diagnosis was rheumatoid arthritis in September 2011. What has happened since is a winding complicated path of autoimmune, neurological, and mental health diagnoses. I’m at a point now, where my specialists laugh when they ask me if I have been diagnosed with something new at each visit.

My health is anything but textbook — and the results of my autoimmune diseases have been unusual and complicated. After 10 years I have just come to accept this. And even when I discover something new and difficult, after I grieve and struggle through it, there is acceptance at the end. I face everything that comes my way regardless of how overwhelming or difficult it is.

There is one thing that I will do everything in my power to avoid at all costs: go to the ER. It creates trepidation, anxiety, a total lack of certainty. I am confident that I should have faced it at least once or twice more than I have in the last 10 years, but I did not.

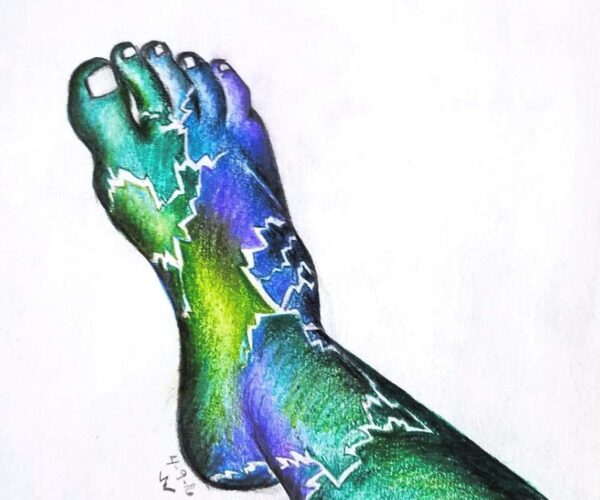

I have had several chronic migraine episodes that lasted a couple days, making it nearly impossible to see, keep food down, or function. I have had a rheumatoid arthritis flare that caused pain so bad I almost passed out. I could not walk, eat, dress or undress myself, sit up on the couch or follow a conversation. I have also had pain flares in the last couple of years from my small fiber polyneuropathy (SFPN) that hurt so badly my skin turned bright red, rashes appeared all over, and I could not tolerate my clothes touching my skin. I couldn’t get my clothes off fast enough before the pain was so bad. I was crying. This is significant because I have an extremely high tolerance for pain; my body just numbs the pain until it hits a certain threshold. I had a port-a-cath placed in my chest and zero pain during the recovery from the surgery.

What I should have done in all of these cases is go to the ER. I should have sought help to control the pain that was wracking my body, destroying my ability to communicate and function. But the ER is not a safe or welcoming space for patients like me.

An Unexpected Trip to the ER

Back in 2016 I went for a job interview. Afterward I was walked out by a person in the department — we were chatting and ended up walking all of the way to the front door so he could answer all of my questions. Outside, as I was stepping down the front steps to the parking lot, I missed a step and fell. My ankles are weak and always have been, probably because of a birth defect I have. My right ankle rolled right, so the sole of my foot faced left, and I landed directly on top. It took my breath away for a second. I was embarrassed and afraid I could not get up because of my limited movement. I also do not tell employers about my health issues during job interviews, so I did not want him to know and return with the information to the hiring manager.

I took a deep breath and got up as quickly as I was able, thanked him, and assured him with a smile that I was fine. I took directions from him on how to get out of the parking lot and walked away, trying not to limp. By the time I got back to my job, my foot and ankle (up to and including my knee) were swollen. The pain was intensifying by the minute. I tried putting ice on it, but that was absolutely no help. So, I called my ex (partner at the time) to take me to the ER because I knew this was really bad. He picked me up and took me. I was honest in filling out what I was diagnosed with, my meds, what was wrong, etc. Then we had to wait, all the while the pain was getting worse and worse. They finally called me back.

I laid on the bed with tears welling up in my eyes. I had pain medicine myself. I was prescribed it and was not actually looking for pain relief. All I wanted was my ankle and leg to be looked at by a doctor to be sure nothing was broken. I needed to be sure that surgery or anything similar was not in my future. If I needed surgery, I would have to go off my biologic, and the consequences would be dire for me. My immune system is a beast. Within two months I would not be able to function and within three months, I would not be able to work. Biologics have always either started showing promise within two weeks for me or I start going downhill quickly within two weeks. My care has to be aggressive because I have high anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-ccp) levels and I have moderate to severe seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. And, as I said, my immune system is a beast that takes no prisoners.

Then….

While I was laying there worrying that I might have to go off my biologic, what the future of my job might be, that I had to leave work, how bad my ankle might actually be because I have a high tolerance for pain, etc., this male nurse comes in briskly with his clipboard and reads over my chart. He sighs. He looks me up and down —head to toe. He reads my chart again. Then he speaks.

“You know, we don’t have any pain meds that are stronger than what you are already taking. So, I am not sure what we can do for you.”

I stared at him in shock for a second, absorbing the distaste and the accusation that just hung in the air like cigarette smoke staining the walls. He didn’t move to come over or even try to examine me. No care. No kindness. No help. Nothing.

I responded: “I don’t care about that. I fell and I need to make sure I didn’t break anything. Or be sure I didn’t tear anything. If I need to have surgery, I have to go off my medication and I need to talk to my doctor about it.”

He visibly relaxed, his shoulders dropping to a normal level. He then changed his tune and looked at my ankle. He told me I would get X-rays and then the doctor would be in. I ultimately did get a morphine shot to help take the edge off my leg. But it certainly didn’t take the pain away. And the nurse was the one who pushed me to take it because he could now suddenly see how much pain I was in. So, despite being honest and just seeking X-rays and emergency care, I was treated like a drug seeker based on my medical history and medication on my list.

Another Visit, Another Roadblock

The other pivotal ER visit for me was when I had a panic attack one month after I was first diagnosed. I was absolutely overwhelmed with the decisions about medicine, what was happening to my body, dealing with the loss of functionality, how bad I really was, worry about keeping my job. My ex thought I was having a stroke at the time because I started stuttering and I couldn’t get out whole sentences. I couldn’t focus. I almost passed out.

We were at the ER, and I was back in a room hooked up to all these monitors, including heart monitors. They had drawn some blood and done some preliminary testing. Once I calmed down, I was able to write out my medication list for them. A bit later the doctor came into my room with a gaggle of nurses behind him. Some were called out for different emergencies, but he still had several of them staring at me while he talked to me. It was unsettling.

He started talking to me about rheumatoid arthritis and admitted that he had not studied or dealt with RA very much. Then we began to talk about my medication list, and how he had no idea what I was taking or the types of medication they were. It was so frightening to talk to a doctor who knew so little about my disease or how to handle it.

Because he was not confident with understanding the medicine, he did not give me certain meds they would normally give someone in my situation. He just did not want to risk it. So, I laid there frightened — afraid of what would happen with this inexperienced doctor who had no idea how to treat me and who wanted me out the door.

My only saving grace was one nurse. After the doctor left, she came back by herself. She sat next to my bed and started talking to me. She had been a nurse in a rheumatology office almost her entire career and had just left to work in the ER. She held my hand, listened to me, let me cry, and encouraged me. She is the only reason I did not have another panic attack in the hospital that day. She gave me hope and the courage to know I could handle what was happening to me.

Prepping for the ER

These experiences taught me some important lessons that could help me if I need to go to the ER again. And even though I still have intense trepidation about the ER, having these in place will make the process more solid and make me feel safer. SoI want to share them with you, and I hope you will share any of yours that you may have. Dealing with the ER is a treacherous experience for complex patients and anything helpful is most appreciated.

If possible, bring a an easily accessible folder, with current paper lists of the following. You can prepare now by making several sets of these lists and just keeping them on hand:

- All medications you’re taking — include frequency/dosage

- Your doctors — include contact info

- Emergency contacts — immediate contact info

- Your diagnoses, including short explanation of your diagnoses — most life-threatening ones

- Sensory overload triggers related to the hospital — a sticker for front of folder

- Copy of your vaccination status — if you have been able to be vaccinated/or not and why

In addition, consider doing the following:

- Bring sensory/safe kit that relieves anxiety — squishies, snoopies, weighted blanket, etc.

- Research hospitals and know what is close (you can ask ambulance for a different hospital)

- Ask your specialist if they are associated with a certain hospital — record keeping is easier

- Say no to a test or exam if you don’t want it

- Make it clear to your emergency contacts what you want in an emergency

- N95 mask for yourself, with several backups — for whomever might accompany you as well

Of course, there are also additional important elements depending on your individual needs. For example, an interpreter for a person who is deaf or heard of hearing or only speaks Spanish, or noise canceling headphones or a sensory kit for a person who is autistic.

The importance of all of this is that when an emergency happens — all this information will ensure you get the best care and as smoothly as possible. Feel free to add what works best for you. And please share with us.

Be a More Proactive Patient with ArthritisPower

Join CreakyJoints’ patient-centered research registry to track your symptoms, disease activity, and medications — and share with your doctor. Sign up.