This story includes mention of suicidal ideation, which may be disturbing to some readers. If you or someone you know need help, consider calling the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 800-273-8255 or the Trevor Project Hotline (for LGBTQ youth) at 866-488-7386.

In late 2011, I was a 16-year-old kid on an examination table, waiting for a doctor to take my invisible symptoms seriously, to provide answers that might provide solace from my debilitating chronic pain. That particular appointment, unlike the countless ones prior, gave me a conclusive diagnosis of bilateral sacroiliitisand ankylosing spondylitis (AS). At the time, I was oblivious to what those words meant for my body, mind, and future. Soon, my trajectory from adolescence to young adulthood became characterized by weekly self-administered biologic injections and an accumulation of more diagnoses.

I am now 26 years old, and this month marks the 10th anniversary of my AS diagnosis on November 11. That year became a turning point in recognizing that what I was going through was real and would eventually become a part of me. In the decade since my AS diagnosis, I have oscillated between flares, fear, and consistent suicidal ideation, all alongside loving community, patient advocacy, and a practice of artmaking.

I have learned to survive by loving and listening to my body for exactly what and where it is.

This year, I am celebrating and honoring my diagnosis anniversary by sharing my story through 10 things I have learned over the last decade of living with ankylosing spondylitis. Although this list is incomplete and continuously evolving, I hope it shines light on the multifaceted, complex, and often contradictory nature of chronic illness.

1. I am the narrator of my own experiences

As a teenager going through a painful and prolonged misdiagnosis process, I became quiet and depressed in and out of clinical spaces. I had the immense privilege of having my mother by my side to help communicate my symptoms to providers. Her health literacy undoubtedly supported my diagnosis process, especially since so many doctors did not take my pain seriously.

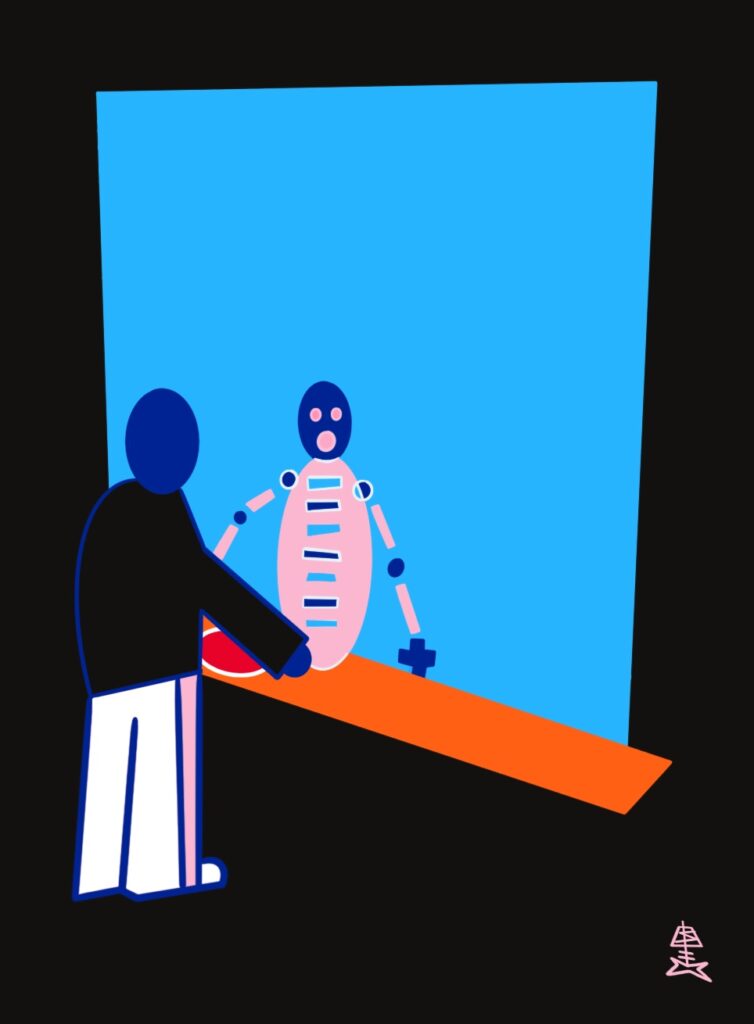

But as I have grown up with chronic illness, I’ve learned that I need to be my own biggest advocate. No pain scale, diagnostic measure, or loved one can articulate my unique lived experiences with ankylosing spondylitis. Only I can speak for myself in a language that feels most representative to me. Often, nonverbal storytelling, such as visual art, allows me to communicate on my own terms.

2. I am allowed to grieve

Grief, like aching pain or heavy depression, often shows up in my body unannounced. Sometimes, grief comes to me when I am sitting on the subway or when I am lying in bed during a moment of solitude. I grieve for my inner child, who had no choice but to grow up and while learning to live with physical pain. I grieve for the dreams I once had that I cannot fulfill. When my pain became debilitating, I had to quit playing competitive basketball.

Although I learned how to better manage my symptoms — and continued to play lacrosse in college — the pain of having to give up my first love of basketball has stuck with me. When I watch professional basketball games now, I have learned to hold grief alongside joy for the sport. Allowing myself to grieve for what has been lost to illness has been an important step in my journey.

3. My body/mind belongs to me

When you have had your behavior, symptoms, mood, and body pathologized for years on end, it can create a profound dissociation in your sense of self and how you move through the world. It is difficult to not see my body as fragmented, with each system or ailment isolated and forced into a hierarchy of need.

I have often felt like I exist in a shell of a body that is not mine, a body that is complicit in my own suffering and surveilled by the medical industrial complex. Taking actions to feel in control of my body, such as getting tattoos and going to therapy, have reminded me that I am not powerless.

Your body is not defined by what health care professionals have labeled you.

4. Identity is multifaceted

Most of the time I do not feel as if there are words that accurately represent myself or my experiences. I tend to switch them around, use them all, or none of them: a combination of chronically ill, sick, neurodivergent, “other.”

I use “crip” or “sick” when I am in activist or patient advocacy spaces to invoke the historical and political patterns of identity reclamation. But on a daily basis none of these labels really feels right, mainly because I live with an invisible disability that is constantly in flux. I have the privilege to pass as able-bodied in most public spaces, which has fostered a sense of alienation with how I identify around others, for fear of stigma or stares by people not believing that I am disabled or sick “enough” to occupy disability seating.

I feel most myself surrounded by my art at home while wearing a patient gown. I am an artist with chronic illness. I am sick, healthy, and other. I am a patient and a human being. The longer I live with illness, the more my identity feels “both/and” — rather than “either/or.”

5. I am not ‘fighting’ my illness

Nor am I “surviving,” “battling,” or “rising above” chronic illness. Quite simply, chronic illness is something that I live with and go through, regardless of how resistant I am to it.

I have found that militaristic language puts me at odds with an opponent I cannot escape: myself. Instead of framing my pain as something I need to “defeat,” I choose to respond to pain with patience and tenderness. My illnesses need my care, not my dismissal or hostility. Consciously being open to see the world for what I am powerfully capable of, while simultaneously holding space for contradiction, allows me to cope with the inevitable days in which I will live with pain.

6. Sometimes getting through a day is all I can do

Ride the wave of pain. Know it will calm in time. Do not be ashamed to ask for help. I’ve learned that care exists in communities and it is okay to need each other; we are interdependent.

I use the Wim Hof breathing method when I am extremely anxious or in pain. I also rely on medical marijuana and cuddles with my cat. It has taken me years of therapy and a loving disability community to recognize my own internalized ableism. This includes my thought patterns and accepting that I am not at fault when I am experiencing a pain flare.

Trusting in the chronic has allowed me to approach pain with tenderness: what ebbs will eventually flow.

7. Not everyone will understand or want to listen to your pain

Choose to surround yourself with people who validate your pain and your experiences. Be honest with yourself about how those around you influence your self-worth.

8. Illness community exists in unlikely places

A few years after I was diagnosed, I received a message on Facebook from Charis Hill, a superstar disability advocate who also has AS. They reached out to start a conversation about the similarities in our stories after reading an article I wrote in high school. They were the first person who told me I was not alone in what I was going through. Fast forward many years, Charis is someone I call a dear friend.

But before I sought out illness community, I first had to be visible to myself and recognize that AS was not going to disappear.

9. A diagnosis is a privilege

Many chronic illnesses have a heartbreaking diagnostic delay. With AS, it can take eight to 10 years from the onset of symptoms to getting a diagnosis. I will never forget what it felt like to go through all those years of misdiagnosis. Doctors told me that my pain was “all in my head,” that AS was a “man’s disease.” My whiteness, my family’s support, and my access to health insurance undoubtedly granted me privilege to diagnosis at a younger age than many folks get.

Moreover, erasure and racism are ingrained at every vantage point in our medical system. Black patients with AS show higher levels of disease activity, impairment, and radiographic severity.

I wear my diagnosis on my sleeve by writing about AS, talking about AS, creating art about AS, and embroidering clothing with AS art to make my experiences visible. This is not only because I believe that storytelling is one of the most powerful ways to advocate for change, but to resist the misrepresentation and invisibility that ankylosing spondylitis faces.

The more that different communities of people with AS speak out about their experiences, the better. AS is not just a disease of young white men, as it is often stereotyped to be. By using our collective voice, we can change the harmful, singular narrative.

10. Art is a lifeline

Whether scribbling on a pad of paper in the dark while my body aches in pain or documenting a trip to the doctor’s office through photos on my phone, creating art and visually capturing my experiences has helped me cope with the ebbs and flows of chronic illness.

Art often feels like a more representative way of communicating. It has given me a platform to make my experiences visible. I’ve learned that my body will tell me what I am capable of. Some days my hands hurt too much to paint, so I create digitally or close my eyes and imagine what my body feels like in color or imagery. Being creative when I am not feeling my best always has a positive impact on my mental and physical states. For me, it is a form of meditation. My art is a collection of visual artifacts, of how and why I have survived to tell my story to this day.

Sal Marx (@salmarx11) is a nonbinary sick artist. They live with ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, and mental illness. As a graduate student in the Master of Science in Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University, their work explores patient-centered health care and the visual communication of chronic illness experiences.

Want to Get More Involved with Patient Advocacy?

The 50-State Network is the grassroots advocacy arm of CreakyJoints and the Global Healthy Living Foundation, comprised of patients with chronic illness who are trained as health care activists to proactively connect with local, state, and federal health policy stakeholders to share their perspective and influence change. If you want to effect change and make health care more affordable and accessible to patients with chronic illness, learn more here.