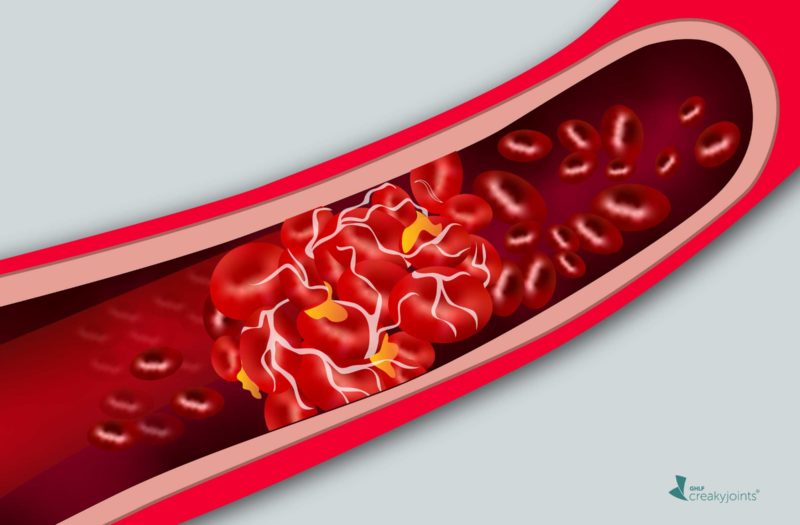

An increased risk of blood clots in the lungs or the deep veins of the legs is just one of the many medical issues that can accompany lupus, an autoimmune disease that affects 1.5 million Americans. First-line therapy for lupus includes the anti-malarial drugs hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine, which has been shown to increase longevity and reduces lupus flares and cardiovascular problems.

“It is well known that hydroxychloroquine reduces the thrombosis [blood clot] risk in lupus,” said Michelle A. Petri, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, in a presentation at the European E-Congress of Rheumatology 2020, held virtually by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). In a new study she and her research team asked how the level of HCQ in whole blood (not plasma, which is considered less reliable) influenced the risk of developing a clot.

The researchers studied the occurrence of blood clots in 812 lupus patients (93 percent female, 43 percent African-American, 46 percent white) followed for years as part of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Measurements taken every three months included whole blood levels of HCQ. During the follow-up period, 43 patients (5.5 percent) developed blood clots, evenly divided between clots in veins and clots in arteries (which can cause stroke, heart attack, or gangrene in fingers or toes).

Using the most recent blood tests before a clot occurred, the researchers found that those who developed any type of clot had significantly lower average HCQ blood levels (695 ng/mL) than those who did not develop a clot (887 ng/mL).

“The rates of thrombosis are reduced 12 percent for every 200 ng/mL increase in the most recent hydroxychloroquine level,” Dr. Petri said.

In the study, the risk of blood clots was also significantly increased in patients with high blood pressure and in those with low levels of the complement 3 protein, a sign of active lupus.

In a separate analysis, the researchers found that higher prescribed doses of HCQ were also associated with a lower risk of blood clots, with a 12 percent decreased risk of blood clot for each 1 mg/kg increase in dose.

However, the researchers found that the dose of HCQ you are prescribed does not predict what your blood level of HCQ will be, suggesting that the best way to personalize the dose for maximal protection against clots is to monitor whole blood HCQ regularly and adjust the dose as needed.

“Everyone wants to know what hydroxychloroquine blood level we should target. It appears that about 1,000 to 1,500 ng/ml might be ideal,” said Petri.

Petri cautioned that the benefit of hydroxychloroquine in lowering the risk of blood clots may be diminished or eliminated if rheumatologists follow the suggestion of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) to gradually reduce HCQ dose in an effort to avoid damage to the retina that can occur with long-term use. HCQ-related retinopathy starts to occur after five years of use and rises with continued use; by 10 years it affects about 2 percent of patients and by 20 years, nearly 20 percent of patients, according to the AAO.

It is important to get regular eye exams and work with your eye doctor and rheumatologist to find the right dosage of hydroxychloroquine for you.

Found This Study Interesting? Get Involved

If you are diagnosed with arthritis or another musculoskeletal condition, we encourage you to participate in future studies by joining CreakyJoints’ patient research registry, ArthritisPower. ArthritisPower is the first-ever patient-led, patient-centered research registry for joint, bone, and inflammatory skin conditions. Learn more and sign up here.

Petrie MA, et al. Hydroxychloroquine Blood Levels and Risk of Thrombotic Events in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Volume 79, Supplement 1. 2020.