Celecoxib (Celebrex), a special type of NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) called a COX-2 inhibitor, has had a rocky history almost from the beginning. When it first hit the market in 1998, it was hailed for its ability to control inflammation in people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) while being gentler on the stomach than traditional NSAIDs like aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen. It subsequently gained FDA approval for acute pain and osteoarthritis, in addition to RA. (You can read more about the different kinds of NSAIDs here.)

But about a handful of years later, it appeared there was a catch.

In 2005, the FDA issued a boxed warning for celecoxib. The main problem: Studies had found that the drug was associated with a substantially higher risk of heart attack and stroke. Then last year, in 2018, there was somewhat of an about-face after an FDA panel reviewed more recent studies and concluded that celecoxib was as safe (or not) as ibuprofen or naproxen. The agency then approved a labeling supplement “to include results from a post-marketing cardiovascular outcomes trial that found that at the lowest dose, Celebrex was similar to moderate doses of naproxen and ibuprofen with regard to cardiovascular safety.”

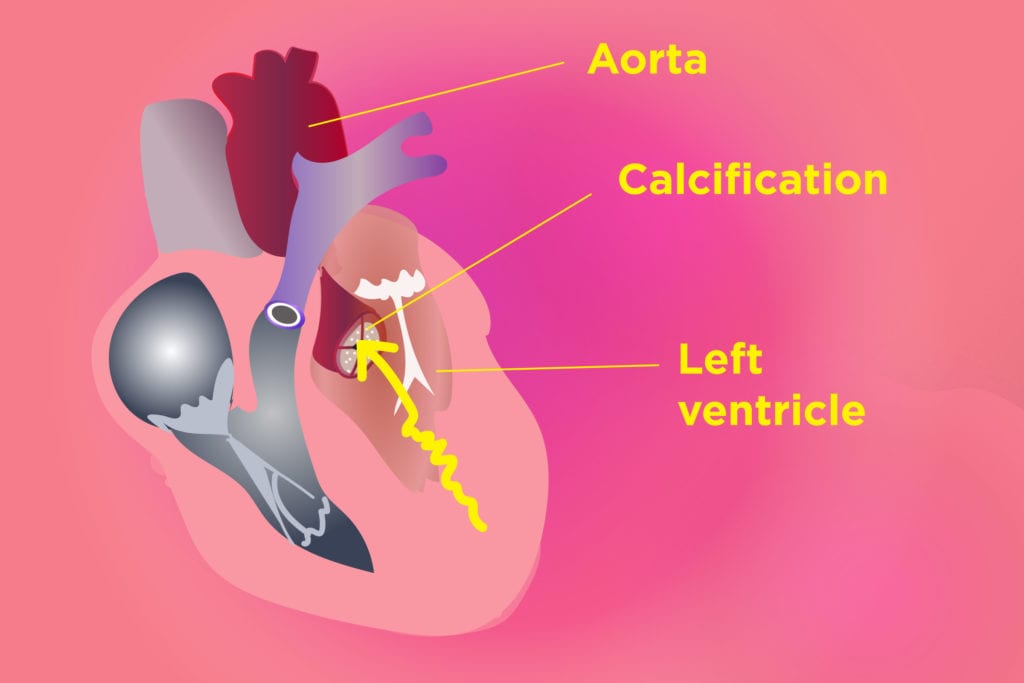

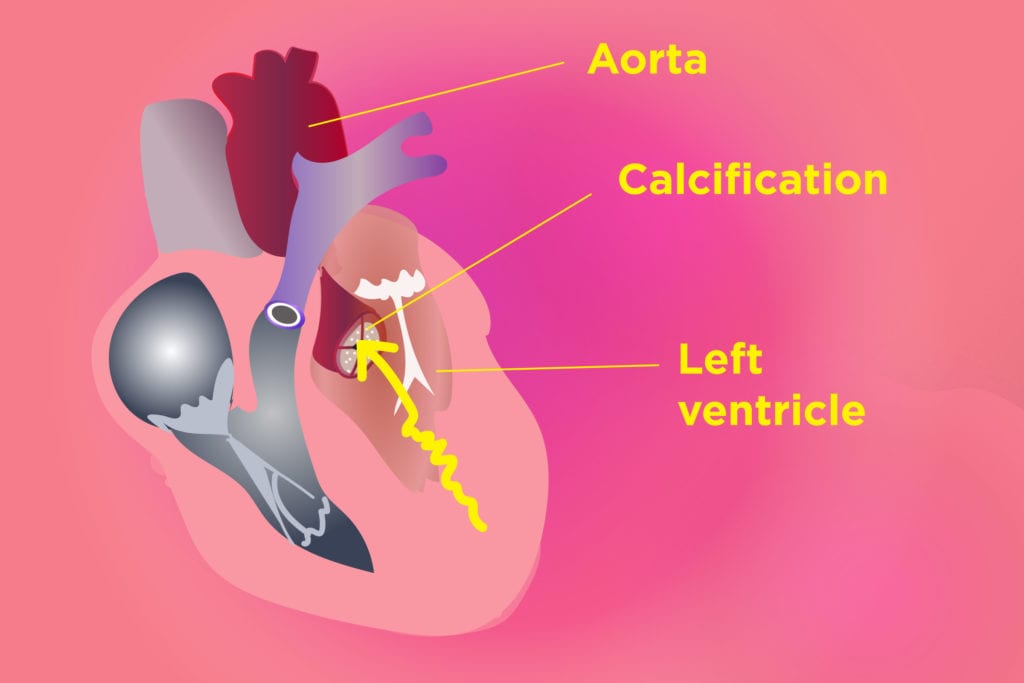

Now there’s a new twist in the story, though whether it will prompt the FDA to make another labeling change isn’t clear. Last month, researchers from Vanderbilt University reported that people who take celecoxib are more likely to have calcium deposits on the aortic valve of the heart (aortic calcification). Calcification can restrict blood flow to the heart by narrowing the opening of the valve (aortic stenosis).

The study, which was published in the journal JACC: Basic to Translational Science, was an analysis of 8,300 patient records. The researchers found that celecoxib use was associated with an increased risk of heart valve calcification. There was no increased incidence of this problem among ibuprofen and naproxen users.

Although this type of analysis doesn’t directly prove that celecoxib causes heart valve calcification, the same researchers also conducted in vitro (lab) studies on aortic valve cells that had been extracted from pigs and saw that the drug had direct effects on these cells.

“Overall, these data suggest that celecoxib use is associated with the development of [aortic calcification],” the authors concluded. “These results suggest that physicians must carefully balance the risks of COX-1 inhibition in the gut [which is what’s responsible for the gastrointestinal side effects linked to other NSAIDs] with those of COX-2-specific inhibition in the aortic valve when choosing a pain control regimen.”

They also suggested that doctors be especially cautious when treating elderly patients who have risk factors for aortic valve calcification.