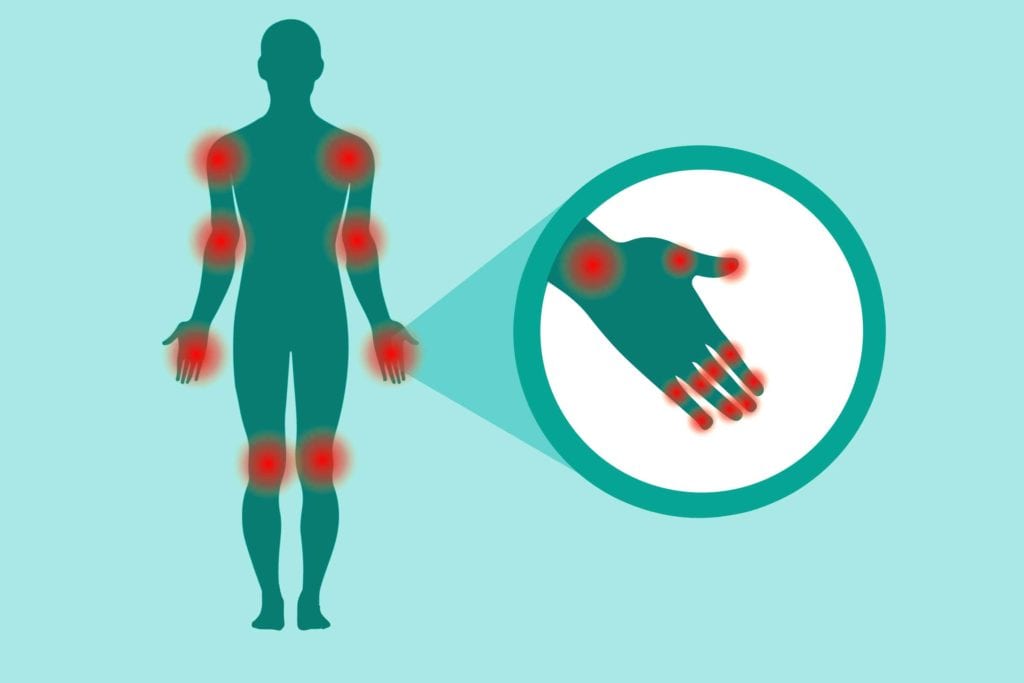

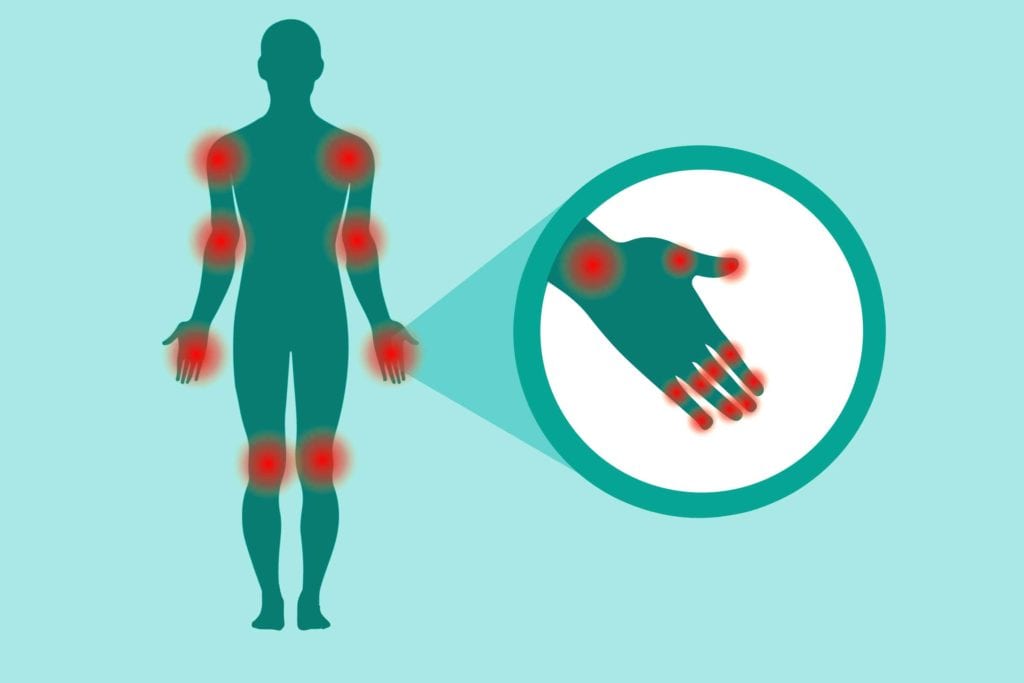

Tallying up the number of tender joints you have is a crucial part of assessing disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Generally speaking, a high tender joint count (as assessed by a doctor during an exam) goes hand-in-hand with worse patient-reported outcomes, like more pain, fatigue, and overall lack of well-being.

While it might seem to logically follow that a high tender joint count would also correlate with objective measures of disease activity, that isn’t always the case, according to a new study, published in the journal Arthritis Care & Research.

To conduct the study, researchers examined data on 209 RA patients that included information from their clinical exams, lab results, and imaging tests at several intervals during a 12-month period. They then grouped the patients into two groups: predominantly tender joints or predominantly swollen joints.

“Tender” means that a patient reports pain in a given joint; “swollen” means that there is increased fluid in the tissues around the joint, which a health care provider should be able to see and/or feel.

According to the study, RA patients with predominantly tender joints had lower levels of inflammation (compared to those with predominantly swollen joints) as seen on ultrasounds. “These findings indicate that inclusion of [tender joint count] in CDAS [or composite disease activity scores] may contribute to misleading information about inflammatory activity,” the authors concluded.

The American College of Rheumatology currently recommends that clinicians assess disease activity by using one or more of six different calculators, many of which factor in tender joint count. That won’t necessarily change, at least not due to a single study.

But it may prompt providers to weigh this aspect of disease assessment less heavily, or to turn to ultrasound or MRI sooner if there are any doubts about current disease activity.