Inflammatory arthritis is a systemic disease, which means that it affects much more than just your joints. Types of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis — as well as other autoimmune diseases like Sjögren’s syndrome and lupus — affect organs and systems all over the body.

The eyes are no exception.

The connection between eye health and inflammatory arthritis goes two ways. In some cases, people don’t learn that they have a form of inflammatory arthritis until they develop eye symptoms, see an eye doctor, and get referred to a rheumatologist for further evaluation. “Some people can present with eye disease early,” says Todd Dombrowski, MD, a staff rheumatologist at Dartmouth Hitchcock in Keene, New Hampshire. Early signs of arthritis in the eye can be overlooked or misdiagnosed until additional systemic symptoms crop up. In other cases, people have inflammatory arthritis and then develop eye complications that also require ongoing management from an eye doctor.

Either way, rheumatologists and ophthalmologists or optometrists need to work together to manage the eye manifestations of inflammatory arthritis.

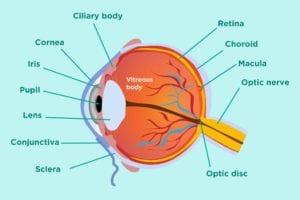

The Structure of the Eye and Where Arthritis Strikes

The eye is a complicated structure. Different types of arthritis can cause different types of eye problems. It’s important to understand some general eye anatomy:

The entire eye is covered by a white outer coat called the sclera. The sclera is covered by a thin semi-transparent mucous membrane that has blood vessels, which is called conjunctiva.

At the very front of the eye is the cornea, which is the transparent layer that transmits and focuses light.

Behind the cornea is the iris, which is the colored part of the eye that helps regulate the amount of light that enters the eye like the diaphragm of a camera. The pupil is the dark “hole” in the middle of the iris, which adjusts in size to let in more or less light.

Just behind iris and pupil is the lens, which is like the lens of the camera. The lens is suspended in the eye cavity through some fine fibrils that attach to the ciliary body.

The back of the eye contains these important structures:

- Choroid: A layer that contains blood vessels, located between the sclera and retina

- Retina: A nerve layer that lines the back of the eye; it creates electrical impulses from light that are sent to the brain via the optic nerve

- Macula: An area in the retina with special light-sensitive cells

- Optic nerve: A bundle of nerves that transmits visual messages from the eye to the brain

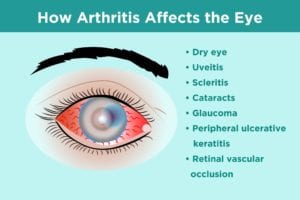

Common Eye Problems in People with Arthritis

Dry eye (keratitis sicca)

Dry eye occurs when you don’t have enough tears or good-quality tears to lubricate and nourish the eye. Tears protect the eye from foreign particles and help maintain good vision. Chronic dry eye from inflammatory arthritis is different from the feeling you get after you’ve worn your contact lenses too long, according to Esen Akpek, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at John Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dry eye can make your eyes feel irritated, make you feel like you have something stuck in your eyes, or cause blurry vision.

Dry eye is a hallmark symptom of the autoimmune disease Sjögren’s syndrome, in which the immune system attacks the body’s saliva- and tear-making glands. Sjögren’s syndrome commonly occurs with rheumatoid arthritis. Up to one-third of people with RA also have Sjögren’s. (Learn more about other rheumatoid arthritis complications here.) Dry eye is also a common manifestation of another autoimmune disease scleroderma, which causes hardening and tightening of the skin and connective tissue.

Without proper treatment, dry eye can raise your risk of eye infection and cause damage to the cornea. If you have dry eye because of an inflammatory arthritis like rheumatoid arthritis, controlling the underlying inflammation with disease-modifying medications can help. Topical eye drops to add moisture to the eye or artificial tears can relieve dry eye symptoms. Depending on the severity of your symptoms, your doctor may also recommend a disease-modifying eye drop such as cyclosporine (Restasis).

You should review with your doctor other medications you take. Certain antihistamines, decongestants, blood pressure medications, and antidepressants can cause dry eye. Your doctor may suggest changing one of these medications or adjusting the dose to help relieve dry eye symptoms.

Uveitis

Uveitis means that you have inflammation that affects the uvea, a middle layer of your eye that’s located between the retina and the sclera. There are three different types of uveitis that are determined by where in the uvea they occur.

- Anterior uveitis is in the front of the eye and is the inflammation of the iris. This is also called iritis.

- Intermediate uveitis is in the middle of the uvea, or the ciliary body.

- Posterior uveitis is in the back of the uvea, or the choroid.

While uveitis isn’t is common among rheumatoid arthritis patients, it does commonly occur with spondyloarthritis, which is an umbrella term for inflammatory diseases that involve both the joints and entheses, the places where ligaments and tendons attach to the bones. These types of arthritis include:

- Reactive arthritis: Joint pain or infection that’s triggered by an infection elsewhere in the body

- Psoriatic arthritis: A systemic, inflammatory arthritis that commonly occurs with the autoimmune skin disease psoriasis

- Ankylosing spondylitis: Inflammatory arthritis that predominantly strikes in the spine and sacroiliac joints that connect the spine and pelvis

Uveitis can cause such symptoms as redness, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, pain, and “floaters” — or dark spots that seem to float in the eye. Typical cases of uveitis are very painful and cause notable light sensitivity, making it hard to be in the sun without experiencing pain the eye. Milder cases of uveitis, however, may have few symptoms, says Helen Wu, MD, an ophthalmologist at the New England Eye Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

It’s critical to treat uveitis — and the underlying inflammation behind it. Without treatment, long-term inflammation in the eye can cause glaucoma, scarring, and permanent loss of vision. Corticosteroid eye drops are typically used first. If uveitis doesn’t improve, then oral steroid medications or injections of steroids in the eye may be recommended.

If you’re prone to regular bouts of uveitis, it may signal to your rheumatologist that you need a change in your arthritis treatment regimen to achieve better disease control. You may also need antibiotics or antiviral medications if an infection is causing the uveitis.

Scleritis

Scleritis means inflammation of the sclera, which is the white of the eye. The sclera is comprised of connective tissue that forms the outer wall of the eye. It is susceptible to many types of arthritis; about half of all cases of scleritis are due to an underlying autoimmune disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

There are two main types of scleritis: anterior, which affects the front of the eye, and posterior, which affects the back of the eye. Posterior scleritis is less likely to be associated with autoimmune arthritis. The three types of anterior scleritis include:

- Diffuse scleritis: Most common type and most treatable

- Nodular scleritis: Causes nodules on the surface of the eye

- Necrotizing scleritis: Most serious form and most likely to cause painful symptoms and complications

Symptoms of scleritis include redness (which doesn’t go away with over-the-counter eye drops), severe pain, blurred vision, and light sensitivity. The eye can turn bluish-purplish red. The pain can be deep and searing. A danger of scleritis is that it can cause thinning of the cornea, which can increase the risk of eye tearing and partial blindness.

Prompt treatment of scleritis is important. Medications include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and corticosteroid pills, eye drops, or eye injections. Surgery may be needed in severe cases to repair eye damage and prevent vision loss.

Cataracts

A cataract means you have clouding of your eye lens, which reduces your vision. The lens of your eye is made of water and protein. Over time and as a normal part of aging, proteins in the lens start to clump together and cloud the lens. As the cataract grows, it becomes harder and harder to see.

However, the assault of inflammation from inflammatory arthritis can cause cataracts to develop sooner than is typical. What’s more, steroid medication used to treat inflammatory arthritis can increase the risk of developing cataracts, especially when used for long periods of time or in high doses.

Symptoms of cataracts include cloudiness in your vision, trouble seeing colors, reduced night vision, more glare from lights or sunlight, double vision or multiple images in one eye, and frequent changes in your glasses or contacts prescription.

Cataracts are typically treated with a surgical procedure to replace the clouded lens with an artificial lens.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that causes damage to the optic nerve in the back of the eye and can lead to vision loss and even blindness. Detecting and treating glaucoma early can help avoid vision loss.

Recurrent inflammation from inflammatory arthritis contributes to glaucoma by increasing pressure in the eye, which can cause nerve damage over time. Glaucoma is also a potential side effect of steroid medication used to treat arthritis.

Glaucoma has few symptoms in its early (and more treatable) stages. When glaucoma progresses to later stages, it can cause symptoms like pain and blurriness. This is why it’s so important to get regular dilated eye exams. When your eye doctor can look at the optic nerve in the back of the eye, they can see early signs of glaucoma and start you on treatment sooner. Glaucoma treatment includes various kinds of eye drops to reduce pressure in the eye; surgery is also an option in patients who don’t respond to eye drops. It’s also important to work with your rheumatologist to minimize your use of corticosteroid medication and try to use the smallest dose for the least amount of time.

Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a condition where the cornea in the front of the eye gets inflamed and is prone to thinning. Many people with PUK also have rheumatoid arthritis; 30 to 40 percent of PUK patients have RA, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is also associated with other autoimmune or inflammatory disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease and lupus.

Symptoms of PUK include pain, redness, reduced vision, light sensitivity, and tearing. The condition can be treated with artificial tears to help the cornea heal and antibiotic drops to help prevent infection. If there is ulceration in the eye, doctors may fill the ulcer with a special tissue adhesive and cover the sore with special contact lenses to control inflammation.

Steroids are also used to get the inflammation in the eye under control, and disease-modifying drugs may be added or changed to help control systemic inflammation. Surgery may be recommended to repair damage to the cornea.

Retinal Vascular Occlusion

This eye problem happens when blood vessels in the retina (in the back of the eye) become blocked (or occluded). Blocked blood vessels in the retina can prevent it from filtering light correctly and lead to a sudden loss of vision. Retinal vascular occlusion is more common among people with atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) or risk factors for cardiac and vascular problems, such as blood clots, heart valve or heart rhythm problems, diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol. Certain types of inflammatory diseases, too, are linked with an increased risk of retinal vascular occlusion, including lupus, scleroderma, and Behçet’s disease.

With retinal vascular occlusion, both veins and arteries can become inflamed and blocked. Blurry or missing vision, along with pain and pressure in the eye or dark spots or lines, occurs suddenly. It requires immediate medical attention.

If a vein becomes blocked, doctors may try to ease swelling in the eye with medication called anti-vascular endothelial growth factor or steroid injections. They may also recommend laser surgery to reduce swelling and help restore vision. Treating blocked arteries is tougher. Doctors can try to relieve pressure in the eye to help prevent further vision loss, but damage that’s already occurred is usually not reversible.

The Importance of Regular Eye Care with Arthritis

It’s critical for anyone with inflammatory arthritis to get regular preventive eye care and to let your rheumatologist or eye doctor know if you’re having new or unusual eye-related symptoms, no matter how minor they may seem. Annual dilated eye exams at the eye doctor are important to check for underlying damage early on. Some eye diseases might not cause a lot of pain or much change in vision, especially in earlier stages, “so an eye exam is always necessary,” Dr. Akpek says.

Dr. Wu requires annual exams from her inflammatory arthritis patients if there are no issues and wants to see patients more frequently if there are any problems.

All of the physicians we interviewed stressed the importance of fostering communication between rheumatologists and ophthalmologists. As a patient, you can help make sure your health care providers are sharing medical records and are up to date on any new symptoms, diagnoses, or treatment changes. Don’t ever assume one doctor knows what the other does.