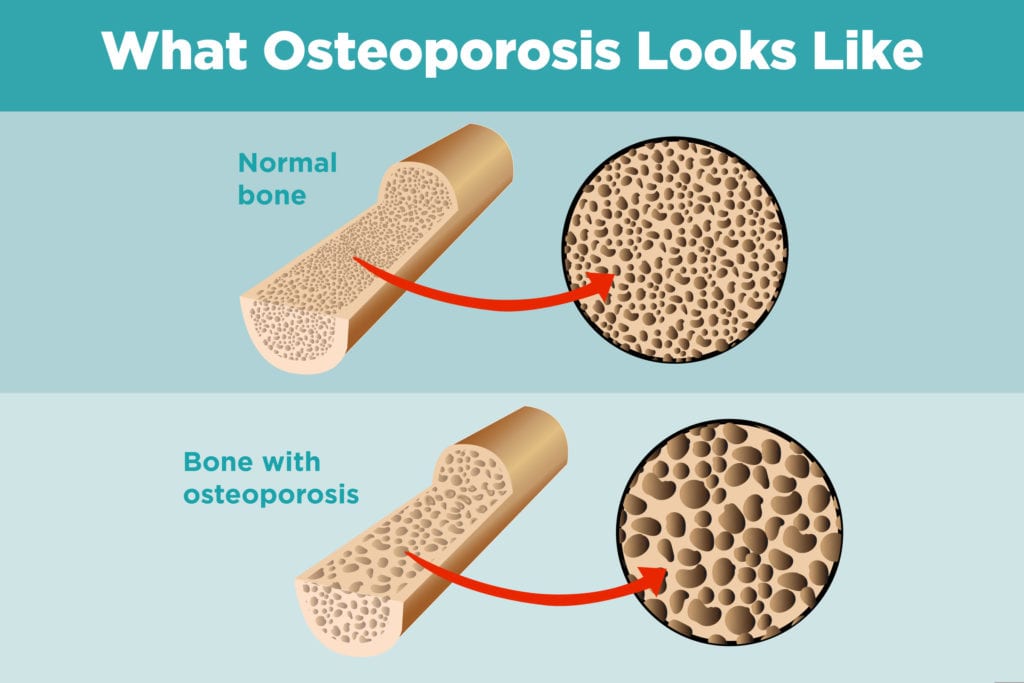

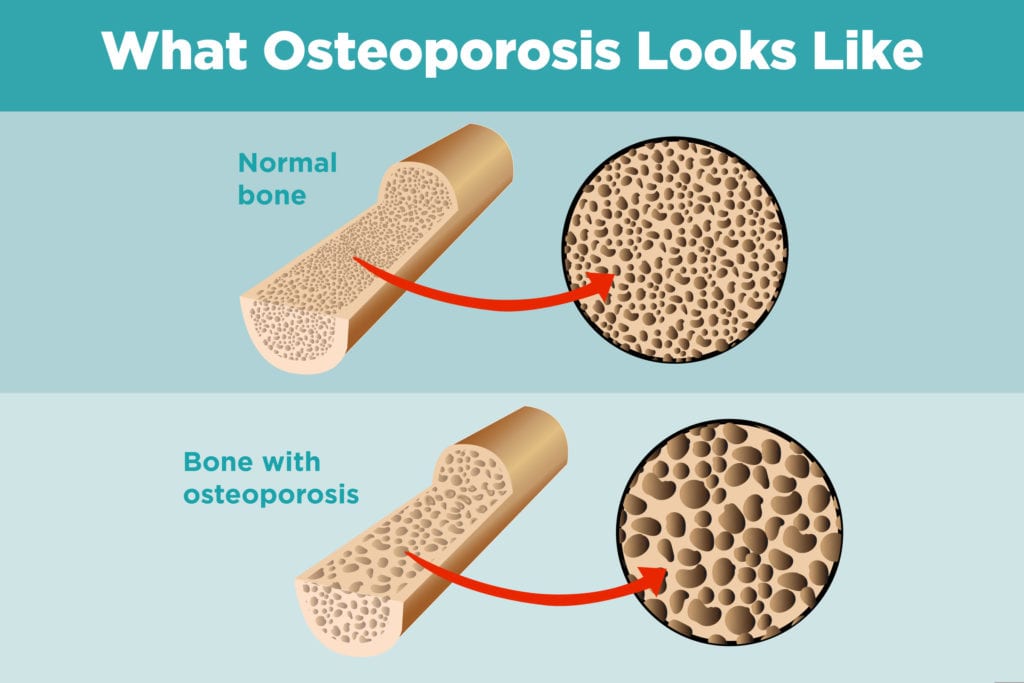

It seems especially unfair when having one chronic illness puts you at greater risk of another. But that seems to be the case with arthritis and osteoporosis. People who have inflammatory arthritis have an increased risk of developing osteoporosis, the bone thinning disorder that can lead to frailty and fractures.

The link between osteoporosis and inflammatory arthritis conditions (such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and lupus) is still not perfectly understood, and scientists are learning the exact mechanisms involved.

“The bone loss generally presents in two different forms: localized bone erosion with bone loss around an inflamed joint and systemic bone loss, or generalized osteoporosis, which is one of the most common extra-articular manifestations of the disease,” according to authors of a 2018 paper about osteoporosis in rheumatic disease.

The osteoporosis risk for rheumatoid arthritis patients is the best studied and understood so far.

“It’s the best studied because it’s the most common of the rheumatic diseases,” says Katherine Wysham, MD, a rheumatologist at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System and the University of Washington. Dr. Wysham has received funding from the Rheumatology Research Foundation to pursue research on arthritis and osteoporosis.

“My research is about trying to find out which patients with rheumatoid arthritis have the greatest risk of osteoporosis,” she says.

Here’s what is known about how having rheumatoid arthritis can increase the risk of developing osteoporosis:

How RA Inflammation Affects Osteoporosis Risk

The inflammation that is central to RA is thought to be a risk factor for osteoporosis in itself. “A lot of data shows that active inflammation in the bone, and systemic inflammation, lead to an increased risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures,” says Seoyoung Kim, MD, a rheumatology clinician and researcher at Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Studies show that bone loss is greatest in the areas immediately surrounding the affected joints, but that systemic bone loss is also increased.

How Inactivity from RA Affects Osteoporosis Risk

“Our patients are hurting,” says Dr. Wysham. “They have pain, which prevents them from exercising. But we know that weight-bearing activity is really important to bones — they respond to that stimulus and become stronger. Without it, the body won’t increase muscle or bone.”

How RA and Osteoporosis Share Similar Demographic Risk Factors

In the general population, the risk factors for osteoporosis include being female, Caucasian, and postmenopausal. And, of course, rheumatoid arthritis is much more common in women than in men.

“But it’s hard to say who within rheumatology is at highest risk,” says Dr. Wysham. She adds, “If you’re diagnosed with a rheumatic disease at a younger age, you may have more risk of osteoporosis because you’re exposed to inflammation and medications like prednisone for longer periods of time, so there’s more time to develop the condition.”

How RA Medication Affects Osteoporosis Risk

Corticosteroids: These potent anti-inflammatories can bring down a flare quickly, but they also come with a host of side effects; osteoporosis among them. “Taking prednisone is a strong risk factor,” says Dr. Wysham. This drug, a corticosteroid, can weaken bones and suppress new bone formation or bone repair.

Proton-Pump Inhibitors: Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs that some patients take to protect their stomach from side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs can interfere with calcium absorption, which is important for bone strength.

Opioids: Less well understood is the link between other drugs sometimes used to treat arthritis and the bone-thinning condition. “Opiates, for example, don’t have a direct causal link,” says Dr. Wysham. “But people on chronic opiates, especially higher doses, can have decreased levels of testosterone or estrogen, and those two hormones are important for bones.”

Disease-modifying drugs: When it comes to disease-modifying drugs — both conventional ones like methotrexate and biologics such as TNF inhibitors — the research gets even more complicated. Since the advent and growth of biologics over the past two decades, researchers have been looking at how all of these drugs can affect bone mineral density, for better or worse.

While studies have found that methotrexate can have a negative effect on bone density among those who take very, very high doses for cancer treatment, the much lower doses used in inflammatory arthritis don’t seem to carry the same risk. In a meta-analysis of six studies, there was no change in bone mineral density in the femur (the thigh bone) or in the lower spine for adults or children with RA on long-term, low-dose MTX.

Some evidence suggests that biologic DMARDs might even be protective for osteoporosis and bone fractures, but the research is not conclusive. A 2018 review paper found that while results varied among different biologics, overall they “reduce systemic inflammation and have some effect on the generalized and localized bone loss. Progression of bone erosion was slowed by TNF, IL-6 and IL-1 inhibitors, a JAK inhibitor, a CTLA4 agonist, and rituximab.” However, a 2012 study of more than 16,000 Canadian patients with RA found that fracture risks were similar among patients regardless of whether they took biologic or non-biologic DMARDs.

Many factors complicate the issue of whether and which DMARDs can have a protective effect on bone mineral density, such as the age of patients (premenopausal or post-menopausal), other osteoporosis risk factors, and history of steroid use.

Other Inflammatory Arthritis and Osteoporosis Risk

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Osteoporosis

Numerous studies have found a link between having SLE and developing osteoporosis and bone fractures. While the risk factors haven’t been as well studied as the link between rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis, many of the same risk factors are involved, according to the Lupus Foundation of America. Like RA, SLE is much more common among women, people with lupus often take prednisone, the disease is characterized by inflammation, and symptoms of the disease can lead to inactivity.

Ankylosing Spondylitis and Osteoporosis

This inflammatory arthritis of the spine affects men — and particularly young men — more than it does women, but osteoporosis is still a frequent complication of the disease. And women are increasingly being diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis and related forms of arthritis.

It’s a bit of a paradox, since in AS the amount of bone formed actually increases as part of the disease progression. But according to an article in The Journal of Rheumatology, it’s estimated that between 20 and 60 percent of patients with AS will develop osteoporosis. Once again it’s thought that inflammation is a major factor, although the exact mechanism is not known. “I don’t think we completely understand yet what the ankylosing process does to bone density and bone strength,” says Dr. Kim.

Complicating the risk in this population is that traditional ways of measuring bone loss, such as bone density scans (see below), are less reliable in people with AS. “Patients with AS get more calcium deposits in more places in their spine that can make DEXA [the type of X-ray scan used for bone density screening] uninterpretable,” explains Dr. Wysham. “And DEXA involves radiation, so you have to think carefully about ordering X-ray imaging in younger patients.”

Psoriatic Arthritis and Osteoporosis

Studies of osteoporosis risk in people with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) have shown conflicting results about bone changes. Like AS, PsA causes both bone loss and excessive bone growth, so determining the overall bone changes and risks in the disease is difficult. Even among studies that do find a link, there’s no consensus about whether men or women are more at risk, or whether the risk increases with the length of time since someone was diagnosed with the disease.

While more research is needed, one thing that is known is that the same trinity of risk factors in RA patients also apply to people with PsA: inflammation, corticosteroid drug use, and inactivity. And because some studies have shown a greater risk of osteoporosis among people with psoriatic arthritis, the National Psoriasis Foundation advises that patients be screened for the disease.

How to Protect Your Bones from Osteoporosis

Many of the recommendations for inflammatory arthritis patients about protecting their bones and preventing osteoporosis are the same as the advice given to the general population. A few things are specific to the disease. Here are steps arthritis patients can take to minimize risk and keep bones strong:

1. Get plenty of calcium and vitamin D in your diet

“Good nutrition — especially calcium and vitamin D — are important for maintaining bone strength,” says Dr. Kim. Good dietary sources of calcium include dairy (low fat is best), leafy green vegetables, and any fortified foods or beverages.

For vitamin D, good dietary sources include fatty fish (such as tuna and salmon), and fortified products (some dairy products, orange juice, and cereals). The body also produces vitamin D from sunlight, although many people in northern climates may not get enough to be beneficial, and others may (wisely) use sunscreen products that protect the skin but also prevent vitamin D from being absorbed.

2. Take supplements if you can’t get these nutrients from your diet or lifestyle

“We check patients’ vitamin D levels once every year or so, and because we’re in Boston, a number of our patients are deficient,” says Dr. Kim. In those cases, over-the-counter or even prescription strength supplements can help.

For people who take PPI drugs because of NSAID side effects, Dr. Kim recommends taking the drug on an empty stomach before breakfast, and then taking a calcium supplement with food to promote better absorption.

3. Try to exercise regularly

Exercise is extremely important for building muscle and bone strength. To protect against osteoporosis, weight-bearing exercises are best. These include things that put weight on your bones, like walking, running, dancing, stair-climbing, and lifting weights. Swimming or using a recumbent bike, while good for your joints, isn’t considered to be weight-bearing.

4. Make other lifestyle changes if necessary

Both smoking and heavy alcohol drinking have been linked with an increased risk of osteoporosis. Smoking can lead to an earlier menopause, which can lead to earlier bone loss. Smoking also makes it more difficult for the body to absorb calcium from the diet. Alcohol is often associated with poor diet, and increases the risk of falls.

5. Ask your doctor about bone density screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — an independent organization of health professionals that makes evidence-based recommendations for preventive medical care — recommends that women be screened for osteoporosis at age 65, or younger if their bone risk is considered equal to or greater than that of a 65 year old white woman. (The USPSTF says there isn’t enough information to recommend screening for men, but the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends screening men over age 70.)

These rules may not apply to people with inflammatory arthritis, however.

“It’s really nuanced in arthritis patients,” says Dr. Wysham. “To better understand who to screen, we can use a special risk calculator, the FRAX. Rheumatoid arthritis is the only one of the rheumatic diseases in the FRAX. If a patient is on steroids and has RA, then the risk calculator recommends screening around age 50 or 55.”

You should ask your rheumatologist if you should get a bone mineral density test to check for osteoporosis.

Based on the results, and any history of fractures, your doctor may recommend that you repeat screenings every few years, or even that you begin taking medication to prevent further bone loss.

6. Minimize corticosteroid use

“I think of prednisone like a Band-Aid,” says Dr. Wysham. “It works immediately. If we see patients who have very active disease, they might require prednisone to immediately calm their disease.” But, she adds, there are many medications that can be used for arthritis, “and our job is to find the right medication in the right doses for the patients so we can take prednisone out of the equation.”

7. Ask about biologic drugs that may actually boost bone

While the jury is still out on the extent to which biologics may prevent osteoporosis or fractures, it’s good to ask your doctor about this as part of the shared-decision making process for choosing which medications to take. Dr. Kim, who studied the bone effects of one of these drugs almost 10 years ago (without finding clear evidence of bone benefit), says that more work needs to be done. “There are a lot of newer drugs now — more than 10 different biologics for RA. All of these agents have different mechanisms, different molecules, and potentially different side effects.”

Until we know more about which disease-modifying drugs may be best protective against osteoporosis, the best thing you can do right now is work with your doctor to minimize your osteoporosis risk factors and work to get your disease under control so that you can be more active.

“We need to emphasize the risk and work it into the routine care of patients, because the sequelae of osteoporosis — fractures — are debilitating,” says Dr. Wysham. “If we wait until someone has a bone fracture, then we’re just reacting to the problem instead of preventing it.”