“Umm, are you OK?” It was a question Melanie Mourt, then 22, would get asked routinely at the end of the group fitness classes she taught during her senior year of college in 2016 at Elon University in North Carolina.

The reason: Her legs would turn a deep purplish-red and become swollen and puffy as class went on.

Mourt tried to brush it off for as long as she could. “I’d say, ‘I’ve just been teaching a lot, I’m overdoing it,’” she says. “Looking back, I didn’t know to the extent.”

Mourt had felt pain in her feet and shins for months, but she chalked it up to overuse injuries from the high-impact kickboxing and weight lifting classes she taught — “very high energy.” She thought they were stress fractures and avoided seeing a doctor because she thought he’d tell her take a break from teaching.

The Clues Start Adding Up

At first, she’d only feel pain while teaching classes. “But then it became all-consuming where I was in pain pretty much the whole day,” says Mourt. “It felt like instead of feet I had bricks at the end of my legs and like my bone was scraping the floor when I was walking. It was excruciatingly painful.”

She felt like she couldn’t grip anything with her hands or completely straighten out her fingers. She was also completely wiped all the time.

“I felt like I was sleeping 14, 15 hours a day and felt like my brain was very foggy, I wasn’t thinking clearly,” says Mourt, who was miserable to be spending her last few months of college feeling physically and emotionally broken.

“There was this whole emotional side of it, where I just felt like, ‘What is wrong with me? I’m 22 years old!’ All my friends are having this crazy social life and I wanted to be a part of that but I was also in this huge amount of pain,” Mourt says.

How Dad Helped Connect the Dots

After a sports medicine doctor did X-rays and MRIs and ran some bloodwork, Mourt was advised to see a rheumatologist. And she knew the perfect one: her father’s doctor.

Mourt’s father has a disease called ankylosing spondylitis, a type of inflammatory arthritis that causes pain in the lower back and hips.

The day Mourt went to the doctor, she remembers sitting in the waiting room surrounded by people who were decades older than she was. “There’s just me, you know, fresh out of college and I remember being like, this can’t be — I’m in the wrong place here.”

But she wasn’t.

Reviewing Mourt’s bloodwork, the doctor asked her what seemed like a completely random question: Had she ever had psoriasis, the skin disease? Mourt recalled a random bout during her junior year of college. “Nobody really understood where it came from, and then it just kind of went away and I forgot about it.,” Mourt says.

She remembers looking at the doctor in disbelief. “I did have this one thing. Could that be related?”

A Crushing Diagnosis

The rheumatologist told Mourt she had psoriatic arthritis, a type of inflammatory arthritis that causes joint pain, stiffness, and swelling, along with the skin lesions of psoriasis.

She didn’t take to the news well.

“I was super angry and grieving for months after that. It took me a long time to understand that this is forever. It’s a chronic disease. It doesn’t go away, no matter how well you manage it. It’s something you always need to be aware of. That’s a lot to take in when you’re so young,” Mourt says.

Then there was the fitness factor. “Physical activity was such a big part of my identity at the time. And it turned out to be one of the worst things for me because it really triggers my inflammation,” says Mourt, who by then had accepted a post-graduation internship at UNC Chapel Hill, where she would design and teach group fitness classes.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BmUGligBWox/?taken-by=mindbodymel

Making a Healthy Lifestyle Pivot

Mourt’s father manages his AS with medication that helps control his symptoms, but after Mourt was first diagnosed, she wasn’t convinced that was the right choice for her. After researching her fair share of treatment approaches, Mourt decided to see a functional medicine provider and follow an autoimmune protocol diet, which advises a strict phase of eliminating what it says are inflammation-promoting trigger foods, such as gluten, dairy, and certain fruits and vegetables.

“I know there might be a time in my life when [taking medication] is something that will really help me, and I’m not opposed to it, but I feel like at this period in my life I want to try to see if I can make a lifestyle change to really support my healing process,” says Mourt, who says she noticed a pain in her hands was gone only a few days after starting the diet.

[Note: CreakyJoints encourages everyone with inflammatory arthritis to talk to a rheumatologist about the finding the right treatment plan for them. These diseases can still cause underlying damage to your joints, bones, and certain organs even if some symptoms improve. Prescription medications are often at the core of treatment due to the strong evidence supporting their success.]

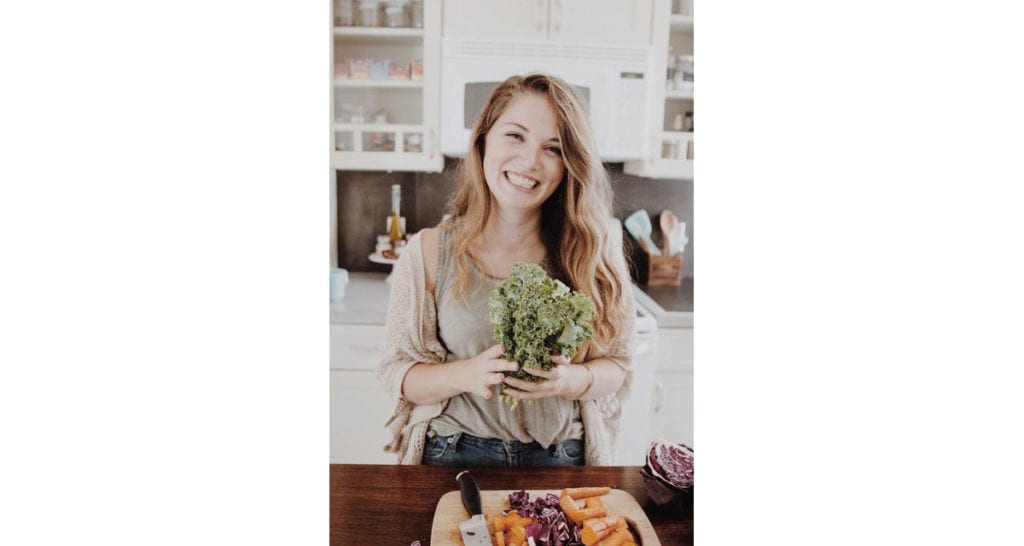

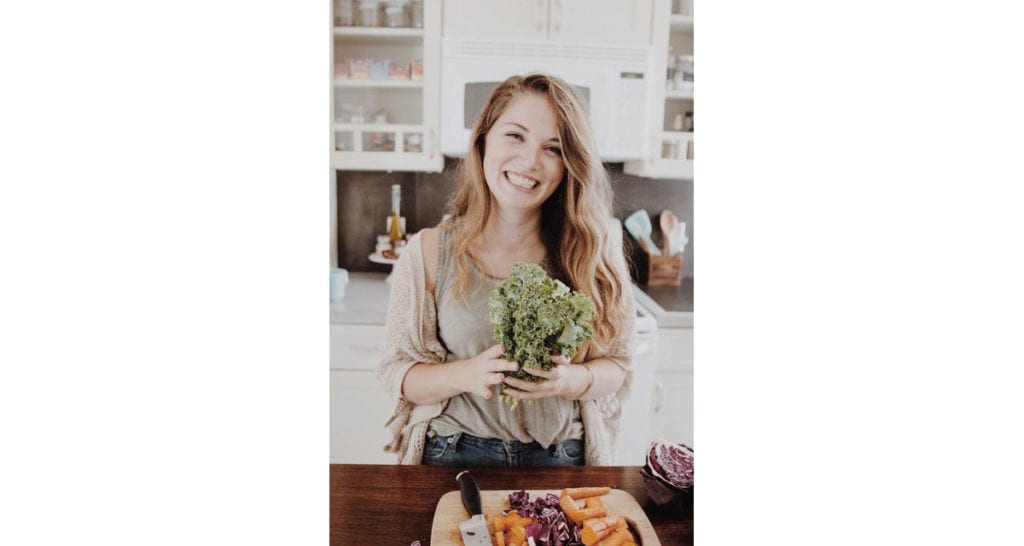

She eats a vegetable-packed diet along with grass-fed meat. “My taste buds have changed. I really do crave a big salad, a warming soup. Carrots now taste really sweet to me. It’s kind of crazy when you start to eliminate those processed foods, your body will let you know what kind of nutrients it needs.”

For breakfast she might eat sautéed kale, a clementine, and some kind of meat, such as a meat patty or leftovers from dinner. Lunch is usually a big salad she can eat on the go. (“I like to combine fresh produce with roasted vegetables and avocado.”) A typical dinner might be veggies paired with salmon or a burger without the bun.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bd_lQjNgub4/?taken-by=mindbodymel

A Less Intense Approach to Fitness

While physical activity would always be a big part of Mourt’s life, she had to find ways to stay active that wouldn’t hurt or debilitate her. Moving to Portland, where she is currently in school to earn a master’s degree in holistic nutrition, helped her rethink things.

“I took a break from any physical activity for a good two months, really let the inflammation come down,” she says.

How to approach exercise with inflammatory arthritis is tricky, she acknowledges. “You want to move because if you don’t move you get stiff and that’s not good, but if you overdo it, it can bring more pain,” she says. “Start slow, ease your way into it, and make sure that your body is ready.”

Mourt goes to yoga three or four times a week — in an 80-degree room that she says is very soothing to her joints — and walks everywhere, especially since she doesn’t have a car.

Soothing Stress to Stop Flares

Mourt says she’s not in pain every day any more, though she will experience flares during periods of high stress. “But as long as I limit my physical activity and tighten up my diet, I’m able to get those symptoms back under control,” she says.

One non-negotiable: sleep. “I have a rule for myself that no matter what I’m going to get to bed by 10:30, no matter if there’s more things that I ‘need’ to get done,” she says. “I’ve noticed that when I don’t get enough sleep, that’s when I start getting anxious and am more stressed out than normal.”

All of this has helped Mourt achieve a much healthier sense of self.

“For a time after my diagnosis, it completely defined me. I couldn’t see myself as anything beyond having this disease,” she says. “As the inflammation went down, my pain level went down, the fatigue went away, and I gained energy, I started to see myself as a person who also happens to have [psoriatic arthritis] instead of an autoimmune patient.”

Follow Melanie’s journey on her website MindBodyMel.com and her Instagram @mindbodymel.