When the average person hears the word arthritis, chances are they think of osteoarthritis. Although there are over 100 different kinds of arthritis, osteoarthritis is the most common and well-known. It is largely a mechanical disorder that’s often caused by overuse or normal wear and tear on the joints as people get older. (However, osteoarthritis can occur at any age — the idea that osteoarthritis only affects older adults is a common myth.)

About 30 million Americans have osteoarthritis. By comparison, about 1.5 million have rheumatoid arthritis, which is among the most common inflammatory types of arthritis.

In osteoarthritis, the cartilage that cushions the ends of bones wears down until the bones are (painfully) rubbing against each other. This usually develops slowly and gets worse over time. Many experts believe that anyone who lives long enough will eventually develop some degree of osteoarthritis, depending on factors like how heavily a joint has been used and whether it’s ever been injured. Not surprisingly, the weight-bearing joints like the knees, hips, and spine are particularly vulnerable to osteoarthritis. The hands, wrists, and shoulders are also common spots.

Osteoarthritis and Inflammatory Arthritis: Similarities and Differences

Osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis like rheumatoid arthritis share part of a name — the word “arthritis” means joint inflammation — but they are very different conditions. While rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease in which the body’s own immune system attacks the joints and causes inflammation, osteoarthritis is a much more mechanical disorder.

Unfortunately, having one kind of arthritis doesn’t confer any immunity against developing another. People with inflammatory arthritis are still at risk of developing osteoarthritis.

Sometimes the same joints are affected with both types of arthritis, and sometimes different joints are targeted. There is an increased risk of developing OA in a joint already affected by RA. When this occurs, it’s called secondary osteoarthritis. Secondary osteoarthritis can also occur after a joint injury or other medical condition.

“That’s why it’s extremely important to get early treatment and good treatment for RA or any inflammatory arthritis. This helps prevent secondary osteoarthritis,” says Nancy Ann Shadick, MD, a rheumatologist at Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The good news, according to Dr. Shaddick, is that “these days, because we have very good treatment for inflammatory arthritis, you don’t see as much secondary osteoarthritis.”

The risk of someone with RA developing osteoarthritis in other joints — joints unaffected by inflammatory arthritis — is the same as the general population’s. It would not be uncommon, for example, for someone to develop rheumatoid arthritis of the hands in middle age, and then develop osteoarthritis in the knee or hip decades later. That type of OA, which occurs with age and use but has no other underlying conditions or causes, is known as primary osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis Symptoms

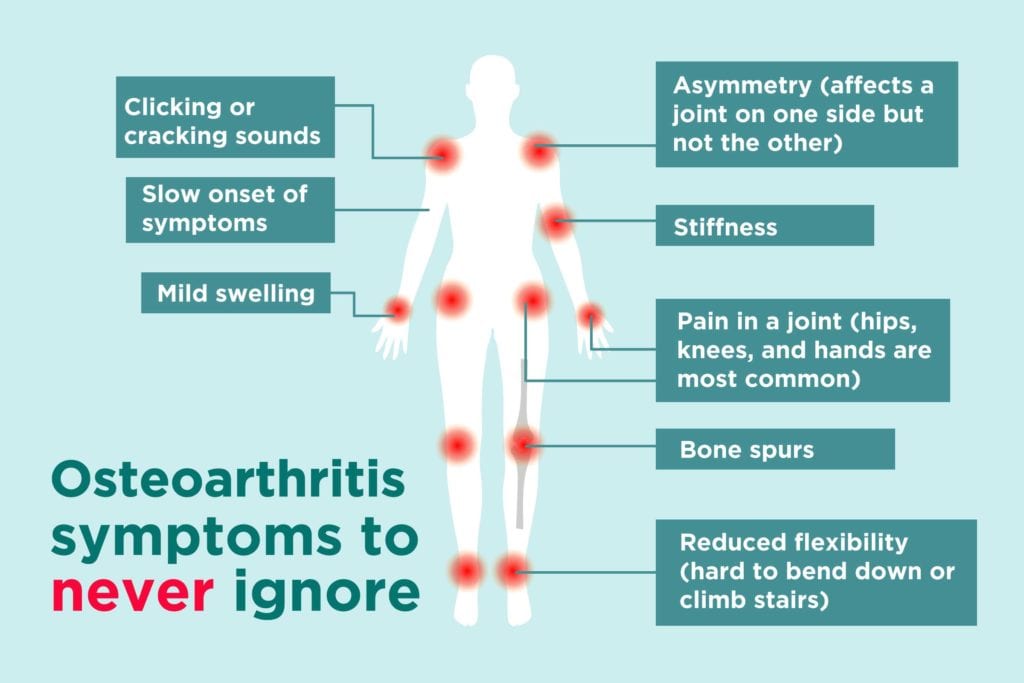

Here are some common early symptoms of osteoarthritis you should know (and here are symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis). If you experience any of these, make sure you let your rheumatologist know rather than assuming that what you’re feeling is simply a new manifestation of your RA or another inflammatory arthritis. Your rheumatologist will make sure you get the right treatment for both.

1. Pain

Pain is the most prominent symptom of both osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, but it’s not the same pain. “In osteoarthritis the joint pain is worse with use, worse as the day goes on, and feels better with rest,” explains Dr. Shadick.

By contrast, the pain of RA tends to be felt more at rest, and isn’t made worse by use. Also, people with RA may feel generally tired and ill from the disease, but OA’s symptoms are usually localized — limited to pain in and around the joints.

2. Stiffness

The stiffness of OA is mostly felt after inactivity, and can usually be relieved by gently stretching or moving the affected area. “People with OA don’t have a lot of stiffness in the morning — generally less than 30 minutes — while people with inflammatory arthritis can have morning stiffness that lasts for hours,” explains Dr. Shadick.

3. Mild swelling

In osteoarthritis the joints may feel achy and tender, but they might not look very swollen or feel warm (the way joints affected by RA do). There may be more swelling after physical activity, and more swelling as the condition becomes more advanced.

4. Bone spurs

Extra bits of bone may be deposited around affected joints in osteoarthritis, making the ends of the fingers look somewhat deformed, for instance, or make the base of the big toe look larger.

5. Reduced flexibility

Joints affected by osteoarthritis may have a decreased range of motion, which can compromise movement. Osteoarthritis in the hips makes it more difficult to bend over. Osteoarthritis in the knees means the legs may not be able to bend as completely. Either can affect walking and stair climbing, among other activities.

6. Slow onset

Osteoarthritis develops very slowly, generally over many years. RA, on the other hand, can develop relatively quickly — over weeks or months.

7. Clicking or cracking sounds

The clicking or cracking that people may hear when they move joints affected by osteoarthritis are the sounds of bones rubbing together without enough cartilage to cushion them.

8. Location in the hands

The hands are a common site for both osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, but the conditions tend to target different joints within the hands. “Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis look a little different,” says Dr. Shadick. “In the hands, for instance, RA tends to affect the knuckles, whereas OA tends to affect the end joints.” (Here’s what to know about osteoarthritis in the base of the thumb.)

9. Asymmetry

It’s common for osteoarthritis to affect a joint on only one side of the body, such as the left knee rather than the right (or vice versa). In RA the disease affects both sides of the body symmetrically, especially as it becomes more advanced.

10. Normal lab results

Osteoarthritis is usually diagnosed based on physical examination and X-rays. There are no specific blood test abnormalities associated with osteoarthritis.

How Osteoarthritis Is Treated

Medical treatment for OA is fairly straightforward, primarily consisting of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen to control pain and inflammation. Steroid injections in an affected joint can sometimes provide relief.

“There aren’t as many disease-modifying agents for OA as there are for inflammatory arthritis,” says Dr. Shadick. “There aren’t as many medications that can stop osteoarthritis dead in its tracks.” The race to discover or develop medications dubbed “DMOADs” — disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs — that would halt or reverse joint degeneration is currently a very active area of research.

Right now there’s no way to reverse the joint damage that has occurred as a result of osteoarthritis. “But there’s still a lot that can be done to reduce the pain and disability,” says Dr. Shadick, citing physical therapy, joint-strengthening exercises, support (such as knee braces), and pain control. (Here are some exercises to help osteoarthritis in the knee, for example.)

The progression of osteoarthritis can be slowed with lifestyle changes, too. “There’s been some very interesting work done on a healthy diet — a diet that’s not high in sugar, high fructose corn syrup, fast food — and how it’s actually shown been shown to slow the progression of OA,” says Dr. Shadick. A so-called anti-inflammatory diet, which may help all types of arthritis, includes fatty fish, healthy fats like canola oil, flaxseed, beans, nuts, seeds, fruits, and green leafy vegetables.

Weight loss, when appropriate, is also helpful, as it reduces the force on the joints. It’s estimated that every pound lost means up to five pounds of decreased pressure on weight-bearing joints like the knees and hips. Losing 20 pounds may relieve 100 pounds of pressure on these joints. “And the most important thing, with both OA and RA, is not to have weakness and muscle atrophy around an affected joint,” says Dr. Shadick. “Once you lose muscle strength around an affected joint the wear and tear can get worse.”

When a joint is damaged beyond repair from OA, and the pain and disability are no longer tolerable even with treatment, joint replacement surgery can help. Surgery used to be more common for people with RA, “but it’s done less now because the drugs for RA are so much better at controlling it,” says Dr. Shadick. But hip and knee replacement surgery is still common for osteoarthritis.

Track Your Symptoms with ArthritisPower

Join CreakyJoints’ patient-centered research registry and track symptoms like fatigue and pain. Learn more and sign up here.