In the short-term, opioids work well for severe pain. If you just got out of surgery or were in a bad car accident, taking an opioid medication might be the best way to get the relief that you need. Opioids work by binding to receptors in the brain and increasing the amount of available dopamine, a chemical involved in the perception of pleasure)

Using opioids for chronic pain like osteoarthritis, however, is controversial because taking these drugs for an extended period means you’re more likely to become addicted to them. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), opioids should not be the first-line of treatment for anyone with chronic pain, unless you have cancer or are receiving palliative care. Instead, the agency urges physicians to try non-opioid treatments — including other medications and non-pharmacologic approaches, like physical therapy — before moving to opioids if necessary.

If health care providers were routinely and consistently following the CDC’s recommendations, it stands to reason that rates of prescription opioid use among chronic pain patients use would be similar across the country. But that doesn’t appear to be what’s happening, according to a recent study.

The study, published in the journal Arthritis & Rheumatology, was an analysis of more than 350,000 people with severe OA who were undergoing total joint replacement surgery while enrolled in Medicare between 2010 and 2014.

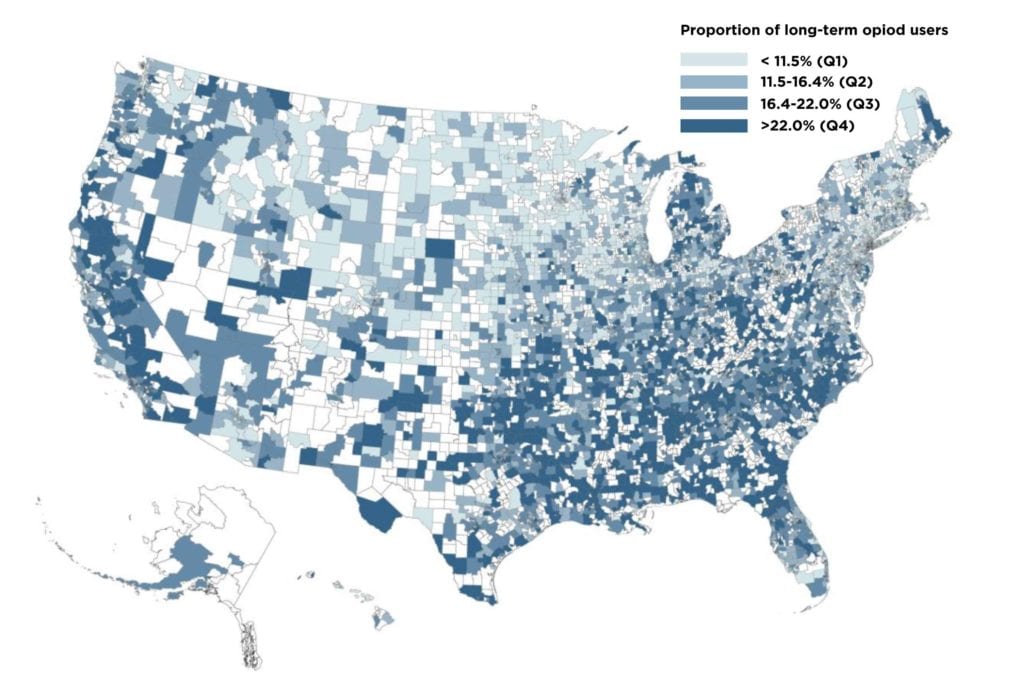

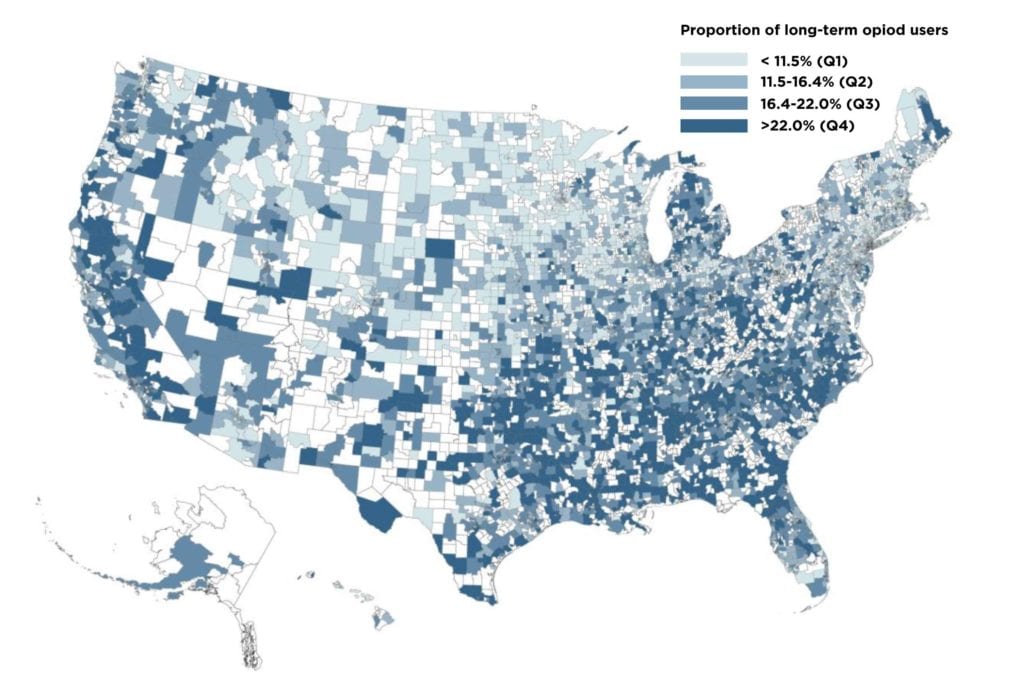

The authors found that opioid use varied substantially, and that the most important factor seemed to be where someone lived in the country.

Overall, the study authors found that “one in six patients used long-term prescription opioids (≥90 days) for pain management in the year leading up to [total joint replacement], with an average duration of seven months.”

But the highest rates of long-term opioid use were among patients who lived in the South and the lowest rates were in the Midwest and Northeast. According to the authors, about 26 percent of study participants in Alabama had been using opioids for at least three months; in Minnesota, that number was lower than 9 percent.

Also concerning: “Nearly 20 percent of the long-term users consumed an average daily dose of ≥90 MME [morphine milligram equivalents], a range that is identified by the recent CDC guidelines as potentially imparting a high-risk of opioid-related harms.” The CDC advises using as low a dose of opioids as possible, because as the dose increases so does the risk of side effects, including addiction and overdose.

“This finding suggests that geographically-targeted interventions to ensure widespread dissemination and implementation of safe opioid prescribing guidelines are necessary to make a meaningful impact on prescribing practices,” the authors concluded.