If you’ve never heard of palindromic rheumatism, you’re definitely not the only one: This form of inflammatory arthritis is rare, and scientists and doctors still have much to learn about it. In fact, one major challenge experts face is whether palindromic rheumatism (PR) is a disease unto itself or a precursor to rheumatoid arthritis (RA), since a number of people who have palindromic rheumatism are eventually diagnosed with RA.

“The biggest reason I wish there was an answer to this is that I would know how aggressive I should be in the management of palindromic rheumatism,” says Christopher Morris, MD, a rheumatologist at Arthritis Associates of Kingston in Kingston, Tennessee. “I also wish I could tell which patients with palindromic rheumatism are going to progress to RA and which won’t.”

While research into such a rare disease is limited at this time, scientists are learning more about the similarities and differences between PR and RA and how to identify and manage it, as you’ll see below.

Symptoms of Palindromic Rheumatism

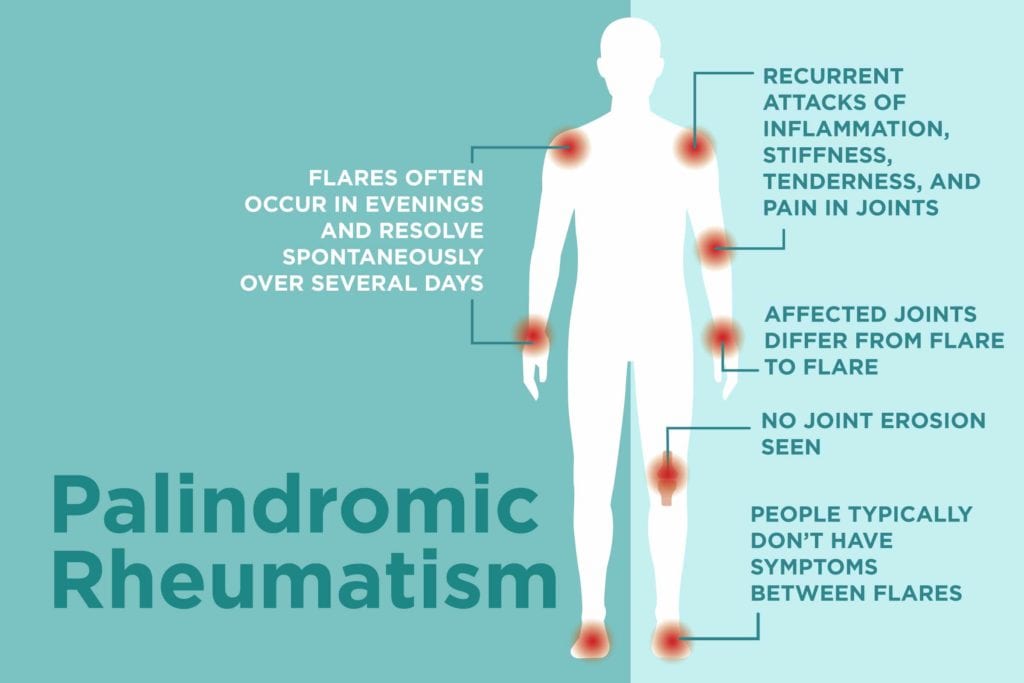

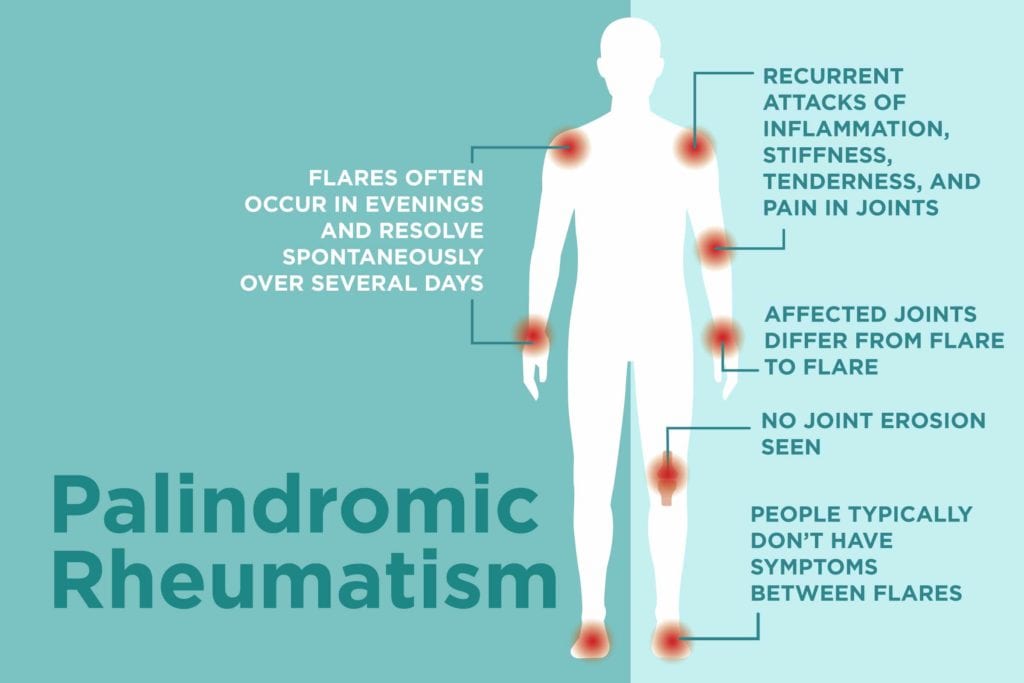

People with PR experience sudden and recurrent attacks of inflammation, stiffness, tenderness, and pain in their joints; some may also have a mild fever, feel fatigue, and develop nodules under the skin.

While these symptoms are also seen in rheumatoid arthritis, palindromic rheumatism differs in that the joints affected vary from flare to flare.

“Palindromic rheumatism is a migratory arthritis,” Dr. Morris says. “One or two joints become inflamed — often in the evenings — and resolve spontaneously or several days after the attack, with the next flare occurring in different joints.”

While any joint in the body is vulnerable to an attack of palindromic rheumatism, the joints in the hands are most commonly involved.

People with palindromic rheumatism may also experience limited range of motion in the joints affected by a flare, but normal range of motion often returns once the flare resolves. In fact, people with PR typically don’t have any symptoms between flares. The time between attacks ranges from days to months, while the flares themselves last for hours to days.

How Palindromic Rheumatism Differs from Rheumatoid Arthritis

Unlike palindromic rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis usually affects multiple joints, and the symptoms are usually symmetrical, persistent, and chronic. Prolonged morning stiffness, one of the hallmarks of RA, is sometimes seen in people with palindromic rheumatism but generally only during flares. And while rheumatoid arthritis affects more women than men, palindromic rheumatism affects men and women equally.

But probably the biggest difference between the two conditions is that joint erosion people with RA experience isn’t seen in those with palindromic rheumatism. For that reason, palindromic rheumatism can generally be managed more conservatively than RA.

How Palindromic Rheumatism Is Diagnosed

There’s no specific test that identifies PR, so doctors must rely on a patient’s medical history, physical exam, and blood and imaging tests to make the diagnosis. It’s best to undergo testing during a flare since palindromic rheumatism symptoms disappear between attacks.

Diagnosing palindromic rheumatism can be particularly challenging since many patients test positive for rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (anti-CCP), which are commonly positive in those with rheumatoid arthritis. And Dr. Morris says that while X-rays of the hands can be useful in identifying palindromic rheumatism, they’re of limited value early in the disease process. (The results would be normal for those with palindromic rheumatism because the condition doesn’t cause joint erosion, but X-rays can also appear normal in people in the early stages of RA.)

For these reasons, your doctor will consider a history of migratory arthritis very important in making a diagnosis of PR.

When Palindromic Rheumatism Becomes Rheumatoid Arthritis

It’s unclear how many people with palindromic rheumtism will eventually be diagnosed with RA because the number varies considerably from study to study. One of the more recent (and larger) studies, published in PLoS One in 2018, revealed that nearly 13 percent of palindromic rheumatism patients ultimately developed rheumatoid arthritis. The researchers also found that those with palindromic rheumatism were at a higher risk of developing Sjogren’s syndrome, lupus, systemic sclerosis, and polymoysitis.

Unfortunately, there are no tools available that can identify which PR patients are more likely to develop RA. However, blood tests may be helpful.

“In my experience, patients with palindromic rheumatism who test positive for both rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP antibodies are the ones at greatest risk of progressing to RA,” Dr. Morris says.

Treatment for Palindromic Rheumatism

Some of the same drugs that are used to treat RA are also used to manage palindromic rheumatism. When Dr. Morris diagnoses a patient with palindromic rheumatism, he usually tries one of the milder disease-modifying drugs (DMARDs) first, such as sulfasalazine or hydroxychloroquine.

“I’ve had a fair amount of luck with these, where patients’ flares are reduced in frequency and severity,” he says. “If these don’t work, I’ll advance treatment to include [other DMARDs] methotrexate or leflunomide. My rationale is that if this is early rheumatoid arthritis, perhaps I can catch it in the early stages so I might be able to prevent a molehill from becoming a mountain.”

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can also help keep the inflammation of palindromic rheumatism under control. If a particular flare is intense, your rheumatologist may use steroid injections to bring quick relief to the affected joint(s).

Generally speaking, the outlook is good for PR patients, Dr. Morris says: “Many people do not see a lot of progression of their disease, and if we can find something that prevents the flares, then they do quite well.”