Writing and reporting by Susan Jara and Steven Newmark

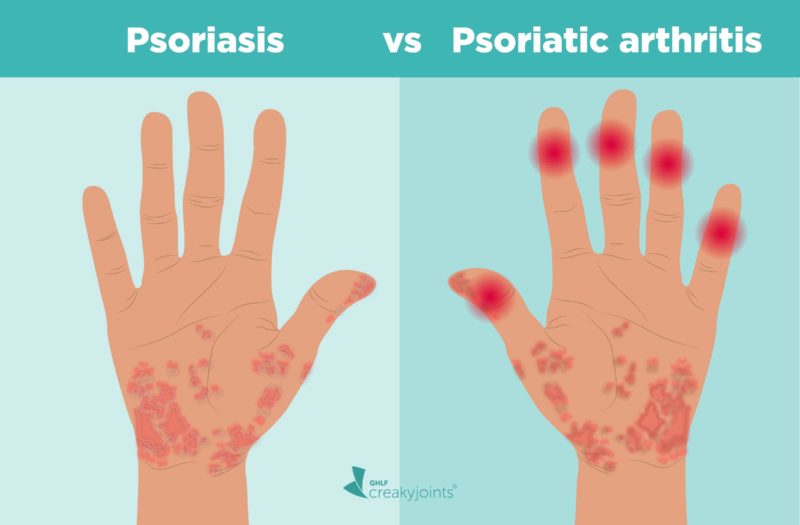

Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are distinct conditions, but they are connected. In fact, data show that up to 30 percent of people with psoriasis will go on to develop PsA and 85 percent of people with PsA also have skin psoriasis.

“Although people can be diagnosed with PsA without having any skin involvement, most often they will have a family member with skin psoriasis,” says Rebecca Haberman, MD, a rheumatologist at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

Psoriasis is an inflammatory condition of the skin, while psoriatic arthritis also includes inflammation of the joints and entheses (places where a tendon or ligament attaches to the bone), called enthesitis.

Read on to find out the different symptoms of psoriasis vs. PsA, how they are diagnosed and treated, and what you need know about the link between these health conditions.

How Do Psoriasis and PsA Overlap?

“For every 10 patients who walk in the door with psoriasis, about three or four of them will eventually get PsA,” says Elaine Husni, MD, MPH, vice chair of the department of rheumatic & immunologic diseases at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. Most cases almost always start with the skin condition and then within seven to 10 years later, joint pain symptoms start to develop.

“However, skin and joint symptoms can develop at the same time — and, more rarely, joint symptoms can appear before skin involvement,” says Dr. Haberman. While estimates vary, one study showed that up to 3 percent of patients developed joint disease before skin disease, she notes.

In some cases, there may have been skin involvement that went unnoticed or undiagnosed. For example, psoriasis can be sneaky and show up in hidden or private areas like the scalp, intergluteal cleft (the groove between buttocks cheeks), belly button, and inside the ear, explains Dr. Husni. “Since people don’t really examine their scalp or buttocks very often, small psoriasis patches [in those areas] can get missed and delay diagnosis,” she says.

Adds Dr. Haberman: “You might have a small fleck in your scalp that you just think of as dandruff that is actually psoriasis.”

What’s more, people with psoriasis in some of these hidden areas may actually be more prone to PsA. “Studies have shown that you may be at higher risk of developing PsA if you have scalp, nail, or inverse [groin] psoriasis,” says Dr. Haberman.

What Causes Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis?

While no one knows the exact cause of psoriasis or PsA, experts believe that a faulty immune system is partly to blame. Specifically, the immune system attacks healthy skin cells and joints, causing the inflammation, swelling, and pain characteristic of psoriatic disease.

Genetics plays a part, too: “Often [patients] will have other family members with psoriatic disease,” says Dr. Haberman. In fact, roughly 40 percent of people with PsA have at least one close family member with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Research is still ongoing, however, and it’s not clear whether having a family history of psoriasis alone increases PsA risk.

Obesity is also a common risk factor for people with psoriasis and PsA. According to a 2019 study in the journal Medicine, roughly 40 percent of people with psoriasis (and roughly 30 percent of people with PsA) are obese. While it is unknown why obesity is so strongly linked to psoriatic diseases, we do know that obesity is associated with the production of inflammatory chemicals in the body, says Dr. Haberman. “It may be that this underlying inflammatory environment helps predispose the body to the development of psoriasis and PsA,” she says.

Other risk factors for psoriasis include:

- Family history (having one or two parents with the disease)

- Viral and bacterial infections (including recurring strep throat or HIV)

- Stress (high levels can compromise your immune system)

- Obesity (psoriasis lesions/plaques develop in skin creases and folds)

- Smoking (plays a role in risk and severity of the disease)

- Alcohol consumption

- Injury (Koebner phenomenon)

- Sunburn

- Taking certain drugs (including beta blockers, chloroquine, lithium, ACE inhibitors, indomethacin, terbinafine, and interferon-alfa)

Other risk factors for PsA include:

- Having psoriasis (specifically in the scalp, nail, and groin area)

- Family history

- Age (between 30 and 50)

- Obesity

- Smoking

Read more here about psoriatic arthritis risk factors.

Symptoms of Psoriasis

Psoriasis is most often associated with red, itchy, flaky skin patches, usually found on the knees and elbows, and thick, pitted fingernails. However, symptoms can vary from person to person depending on the type and severity of your psoriasis. For example, one person can have just a few patches near their scalp or elbow while other people can have them on the majority of their body.

For most people, psoriasis symptoms tend to come and go, flaring for several weeks or months and then calming down. It can also go into remission, in which your skin may clear almost entirely.

- Silver, scaly patches (mostly on the elbows, knees, and scalp)

- Small, red dots or lesions that may appear after having strep throat

- Red patches of skin (often found in folds of the body, such as in the elbows, knees, armpits, or groin)

- Patches on the scalp that have a red or silvery sheen (that may lead to hair loss)

- Blistery pustules on the body (most often on the hands and feet)

- An itching or burning feeling on the skin

- Dry, cracked skin

- Discolored, pitted nails

Symptoms of Psoriatic Arthritis

PsA is different than psoriasis alone in that it includes joint, axial (spine), and entheseal signs and symptoms, notes Dr. Haberman. Like psoriasis, symptoms can differ from person to person, depending on the type and severity of the disease.

Plaques on the skin

Red patches of skin with silvery scales that can cover large areas of the body or appear on scalp, elbows, knees, and around the ears

Swollen fingers and toes

Red, tender, painful swelling (dactylitis) that causes “sausage-like” toes and fingers

Painful joints

Achy, stiff joint pains (typically in hands, knees, and ankles and on one side of the body) or inflammation in the joints of the spine (axial involvement)

Enthesitis

Inflammation of the entheses, or where a tendon or ligament attaches to the bone, causing symptoms such as Achilles tendonitis or plantar fasciitis

Nail changes

Pitting, thickening, ridging (Beau’s line) or crumbling of the nail; color changes; onycholysis (separation from the nail bed); subungual (debris under the nail)

Read more here about how psoriatic arthritis affects the nails.

Some red flags that you should see a rheumatologist if you have psoriasis and suspect you might be getting PsA, according to Dr. Husni:

- Any joints that are red, hot, and swollen

- Joint pain that lasts greater than six weeks in a row

- Prolonged joint stiffness (greater than one hour)

- Joint pain associated with change in your well-being (i.e. joint pain and fatigue or joint pain and low-grade fever)

Diagnosing Psoriasis and PsA

Unfortunately, there’s no one simple diagnostic test to check for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. This means your doctor will need to make a clinical diagnosis, which requires taking into account your symptoms, risk factors, as well as the results of bloodwork (for signs of inflammation) and X-rays or other imaging scans (MRI, ultrasound, CT scan) to assess any joint involvement.

During the physical exam, your doctor might look for signs of psoriasis — on the elbows and knees as well as less visible places like the scalp, belly button, intergluteal cleft, palms of hands, and soles of feet. They’ll also check for any fingernail or toenail abnormalities, like pitting or ridging, as well as swollen fingers or toes (dactylitis).

“The presence of dactylitis and finger and toenail changes are evidence of psoriasis that can be used to aid in the diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis if there is no evidence of skin disease,” says Dr. Haberman.

Here are some common steps used to diagnose psoriasis and PsA:

- A medical exam to discuss family history, risk factors, and symptoms

- Blood tests to check for markers of inflammation (such as CRP and ESR) and antibodies (such as rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP), which can help rule out other types of arthritis, including rheumatoid arthritis

- Imaging tests (X-rays and ultrasounds) to detect any joint damage, dislocation of small or large joints, disfiguration (arthritis mutilans), new bone formation, and inflammation in the enthesis

- Skin biopsy of a skin plaque, if you have previously undiagnosed psoriasis

Treatments for Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis

Many medications can help treat both the skin and joints, but there are definitely medications that work better for one than the other, explains Dr. Haberman. “When treating PsA, we focus on both domains. We may start with one medication if your skin is worse that is better on the skin, but it should still have effects on the joints,” she says.

According to the clinical treatment guidelines by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF), your personal treatment plan should depend on how PsA is impacting your body as well as the severity of your symptoms.

Since patients with psoriatic arthritis may have different degrees of involvement of skin, joint pain, finger and toe swelling (dactylitis), and pain where tendons and ligaments attach to bone (enthesitis), it’s important to identify the most problematic areas and choose treatment options that are best suited for them, says Dr. Husni.

For example, if you have little joint pain and a lot of skin involvement, your rheumatologist might try newer biologics called IL-17 inhibitors, like secukinumab (Cosentyx) and ixekizumab (Taltz), notes Dr. Haberman.

“While we have a lot of medication options for PsA, sometimes it is more of ‘trial and error’ to see which medication the patient will respond to,” she says. “Sometimes we need to try more than one medication to find the one that is right for that patient.”

Medications use to treat both psoriasis and PsA include:

- NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs): used to treat mild joint pain but not skin psoriasis or nail involvement

- Glucocorticoids: used sparingly and very carefully in people with PsA

- Conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as methotrexate

- Biologics and biosimilars

- JAK inhibitors

What Psoriasis Patients Must Know About PsA

Surprisingly, many people with psoriasis don’t even know about PsA and, for about 30 percent of patients, it takes more than five years to get diagnosed. This is partly because PsA can easily be misdiagnosed, especially if the person does not have psoriasis. “In this case, it may be missed or mistaken for another type of inflammatory arthritis,” says Dr. Haberman. “If only one joint is involved, such a toe, it can be mistaken for gout.”

A 2018 study conducted by our parent non-profit organization, the Global Healthy Living Foundation, found that 96 percent of people received at least one misdiagnosis prior to being diagnosed with PsA.

“If you wait 10 years and just rationalize that maybe you hurt myself, by the time you see a physician and get diagnosed, you’ve accumulated years of disease and inflammation, and your doctor will need to use stronger drugs with potentially more side effects to get the symptoms under control,” says Dr. Husni.

Adds Dr. Haberman: “We know that a delay in diagnosis and treatment of as little as six months can lead to worse outcomes over the long term. We have great medications that can help, so see the rheumatologist so we can talk about the best treatment options. The earlier we treat, the better you will be.”

Not Sure What’s Causing Your Pain?

Check out PainSpot, our pain locator tool. Answer a few simple questions about what hurts and discover possible conditions that could be causing it. Start your PainSpot quiz.

Want to learn more?

Listen to this episode of Getting Clear on Psoriasis, from the GHLF Podcast Network.

Busse B, et al. Which Psoriasis Patients Develop Psoriatic Arthritis? Psoriasis Forum. December 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4206220.

Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-psoriatic-arthritis.

Gottlieb AB, et al. Clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis in dermatologists’ offices. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. July 2009. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09546630600823369.

Interview with Elaine Husni, MD, MPH, vice chair of the department of rheumatic & immunologic diseases at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio

Interview with Rebecca Haberman, MD, a rheumatologist at NYU Langone Health in New York City

Ogdie A, et al. Diagnostic experiences of patients with psoriatic arthritis: misdiagnosis is common. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. June 2018. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.4374.

Psoriasis. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/dermatologic-disorders/psoriasis-and-scaling-diseases/psoriasis.

Psoriatic Arthritis. American College of Rheumatology. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Psoriatic-Arthritis.

Psoriatic Arthritis. Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/psoriatic-arthritis#inheritance.

Queiro R, et al. Obesity in psoriatic arthritis: Comparative prevalence and associated factors. Medicine. July 2019. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016400.

Villani AP, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. August 2015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.001.