If you had chickenpox as a child, you likely remember those itchy bumps and tiny blisters that turned into scabs you weren’t supposed to pick (but did anyway). That very same virus that gave you childhood chickenpox also causes shingles — an even less pleasant viral infection that leads to a much more painful rash. And having inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, may raise your risk for developing shingles.

Here are answers to some commonly asked questions about shingles, and what you can do to minimize your odds of getting it.

What Causes Shingles, Anyway?

Once you’ve had and recovered from chickenpox, the varicella zoster virus (or chickenpox virus) settles into nerve cells near the spinal cord and brain, where it remains dormant for years. In some people, the virus can reawaken and travel along a nerve to trigger a rash in the skin. That second eruption of the chicken pox virus is known as shingles.

Exactly what reactivates the virus is unclear. Aging can play a role; as you get older, your immune system is less effective at protecting you from infection, which may allow the virus to re-emerge. Shingles is most common in adults older than 50, as well as in people with weakened immune systems from certain diseases, like HIV/AIDS and cancer.

Why Does Having Arthritis Affects Your Shingles Risk?

The research is pretty clear: People with rheumatoid arthritis are about twice as likely to develop shingles as otherwise-healthy adults, according to a study published in Arthritis Care & Research. Understanding why, however, is less clear: Experts think it’s likely due to dysfunction in the immune system when you have inflammatory arthritis, as well as effects from the immune-suppressing medications people take to manage their disease.

Corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are prescribed to relieve acute symptoms of RA and are known to increase the risk of shingles: In one 2015 observational study that analyzed data that from more than 28,800 people with RA, researchers showed corticosteroid use and aging were linked to an increased risk of shingles. Conventional DMARDs (disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs) like methotrexate were not associated with a higher risk of shingles.

Other research suggests a higher risk of shingles among people who use certain biologic therapies, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, as well the drug tofacitinib, which is part of a new class of drugs for RA called janus kinase inhibitors, or JAK inhibitors.

What Does Shingles Feel Like?

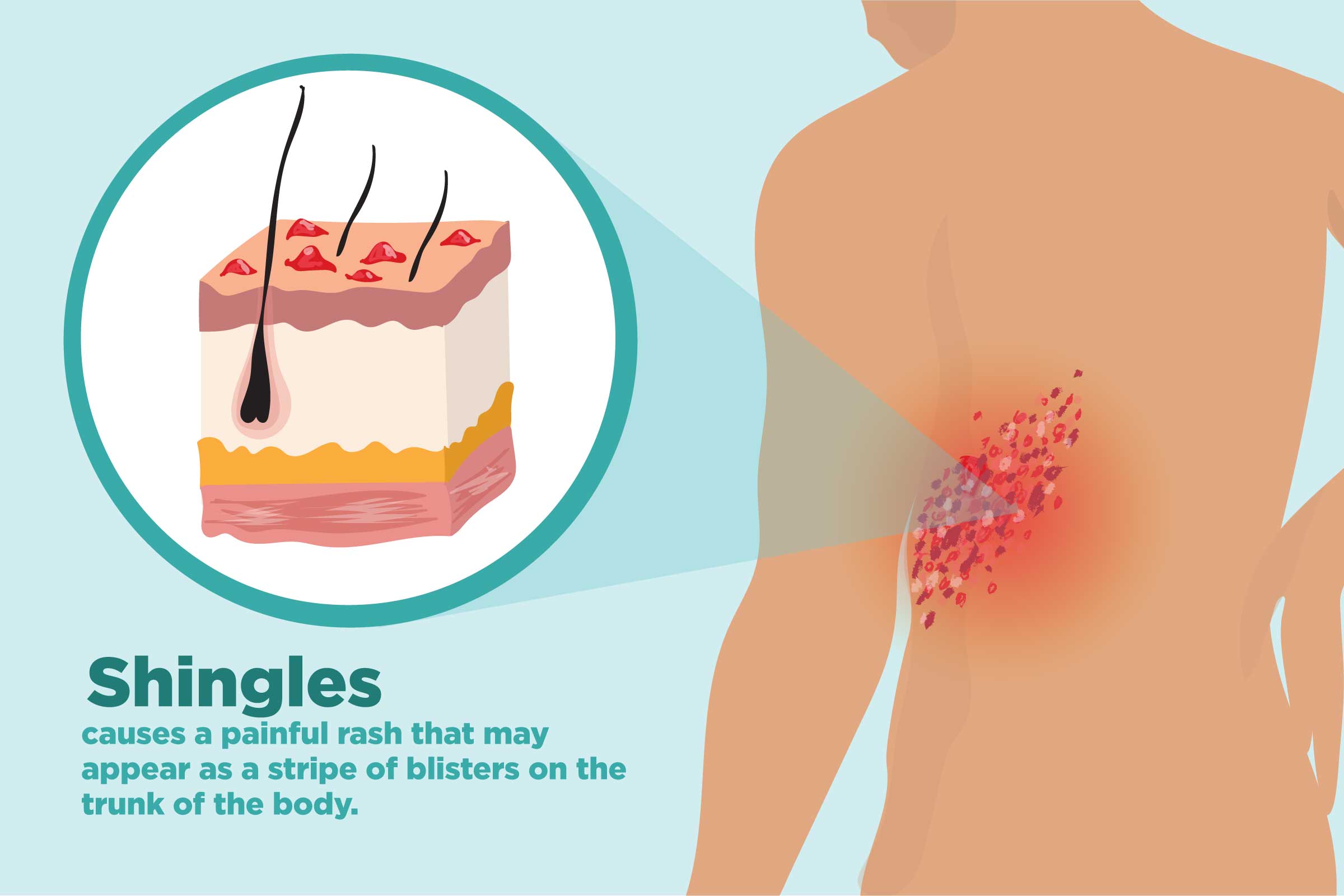

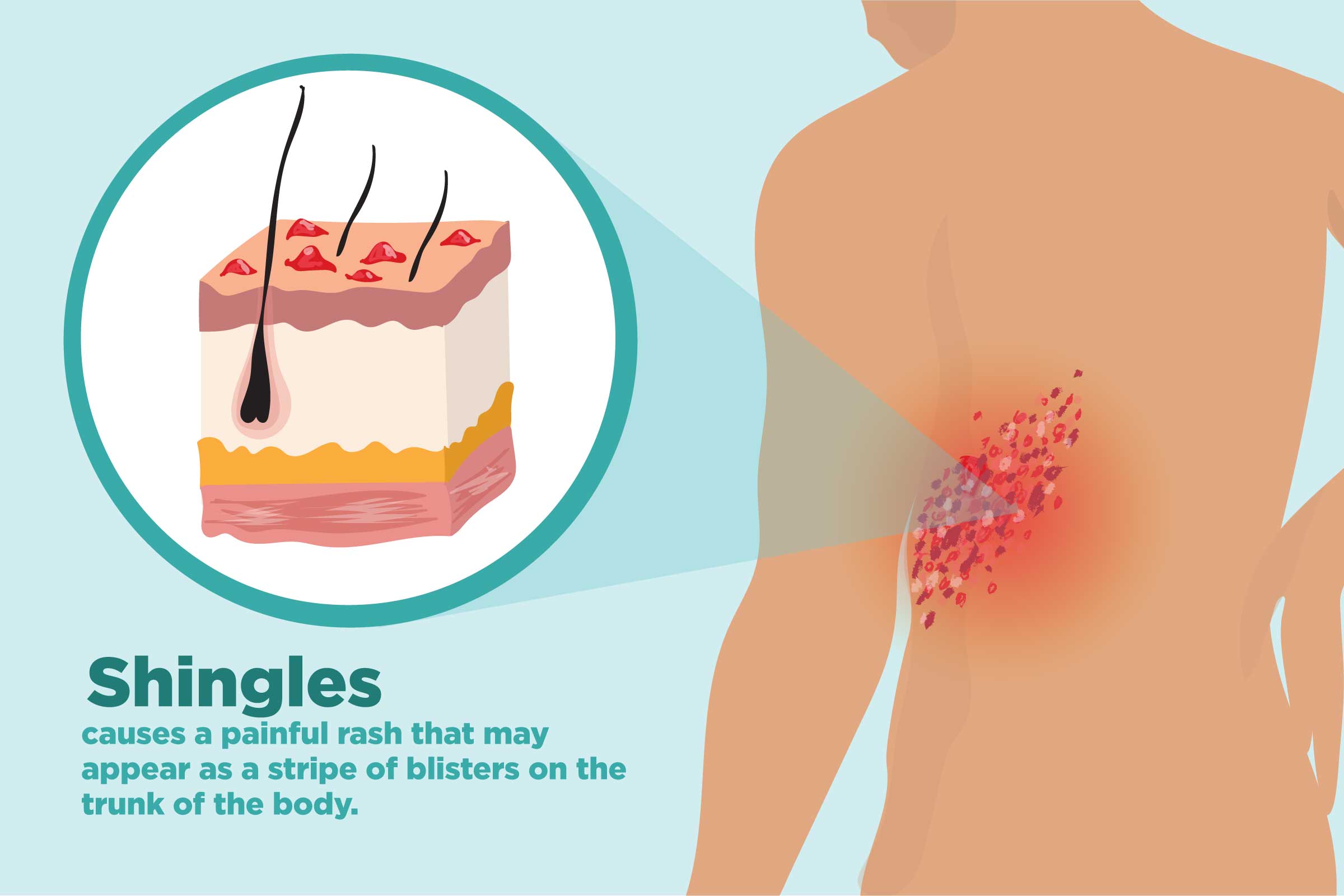

Burning or tingling pain in a small section on one side of the body is typically the first sign of shingles. For some people it can be so intense that even the slightest touch can cause severe pain.

A chickenpox rash often occurs all over the body, whereas a shingles rash usually affects one area. It often strikes on the torso, wrapping your waist in a band-like stripe, or can occur on your face. It looks like fluid-filled blisters.

Other shingles symptoms include itching or numbness. Shingles can also cause fever, headache, and fatigue.

How Is Shingles Treated?

There’s no cure for shingles. If you think you have it, see your doctor right away. Prompt treatment with a prescribed antiviral medication may help you heal faster and lessen the severity of symptoms, as well as reduce the risk of complications. Shingles usually clears up between two to six weeks. One common complication is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), which occurs from nerve damage and causes chronic pain that can last for months after the blisters clear.

Is Shingles Contagious?

You can’t get shingles unless you’ve been exposed to chicken pox and have the virus in your nervous system. If you have shingles, however, you can pass the varicella zoster virus to anyone who isn’t immune to chickenpox. (If they had chickenpox, they usually have antibodies against the virus already.)

The virus spreads through exposure to the unscabbed, oozy, exposed shingles blisters. Once the blisters have scabbed over, they are not contagious. They also can’t spread the virus as easily if they’re covered up well. Shingles is not usually spread from coughing or sneezing.

If someone is infected for the first time with the varicella zoster virus, that person will develop chicken pox, not shingles.

If you have shingles and someone around you later develops shingles, it will be from the varicella zoster virus they already had re-awakening in their body, not from exposure to you.

What Can You Do to Avoid Spreading Shingles?

The varicella virus is spreadable from the time symptoms appear until the blistery rash has scabbed over. You can go to work, run errands, and spend time with other people while you have shingles, but make sure to keep your rash covered and avoid having other people exposed to it. Don’t touch the rash (easier said than done when it’s very itchy) and wash your hands frequently.

And steer clear of at-risk people, especially pregnant women, young children (who haven’t been vaccinated against chickenpox yet), and people with weak immune systems.

What About Vaccines for Shingles?

There are two vaccines available to help prevent shingles: Zostavax, a live vaccine, and the newer Shingrix, a nonliving vaccine that was approved by the FDA in 2017.

Shingrix is now preferred over Zostavax. It is recommended for people age 50 and older, including those who have rheumatoid arthritis (more on this below). It’s given in two doses, with two to six months between doses. (Zostavax is given as a single dose, and approved for adults age 60 and older.)

According to the CDC, Shingrix may be used for adults who are taking low-dose immunosuppressive therapy, are anticipating immunosuppression, or have recovered from an immunocompromising illness.

Though Shingrix has been shown to be more effective at preventing shingles than Zostavax, some experts question whether it’s safe for people with inflammatory arthritis. The Shingrix vaccine was studied in HIV patients, cancer patients, and transplantation patients, who all did fine, Elizabeth Kirchner, MSN, CNP, from the Cleveland Clinic told MedPage Today.

But patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and lupus were all excluded from those trials. The concern: kicking up the immune system in autoimmune patients who already have an overactive immune system, she told MedPage.

“[Patients] should discuss with their providers the risks and benefits associated with the vaccine,” Kirchner advised CreakyJoints. The benefit is a high level of protection against shingles, she says; risks include known short-term side effects, possible disease flares, and/or new autoantibody production.

Getting the shingles vaccine does not guarantee you won’t get the disease; it’s only used as a prevention strategy. You should ask your doctor if Shingrix is safe for you.