Having inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis doesn’t just affect your joints. Because these diseases impact the immune system, they can cause symptoms all over your body — including your eyes.

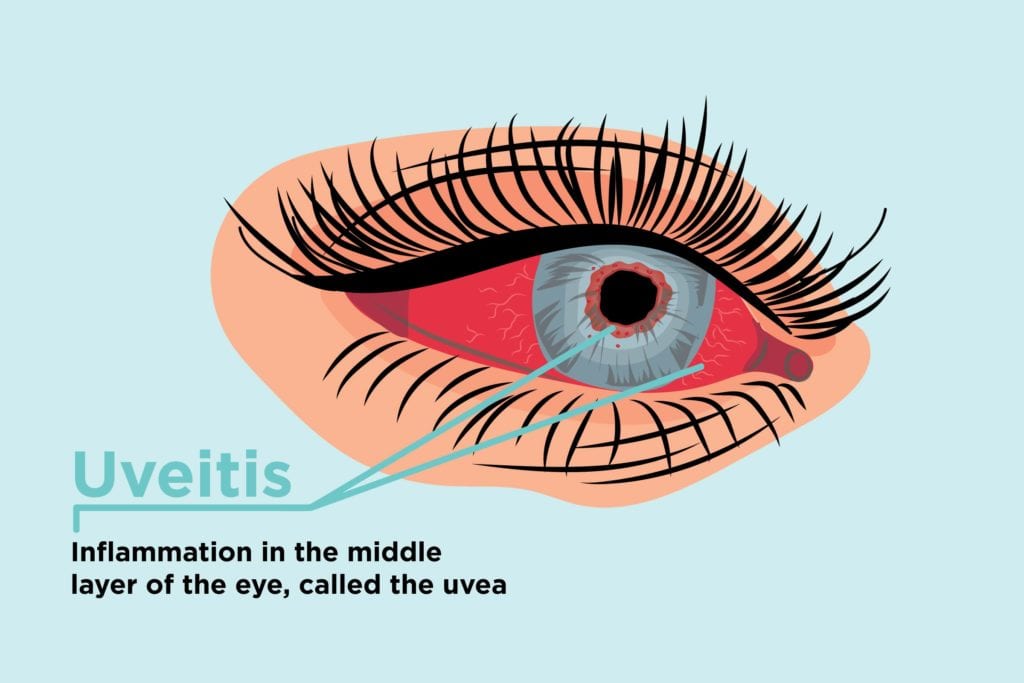

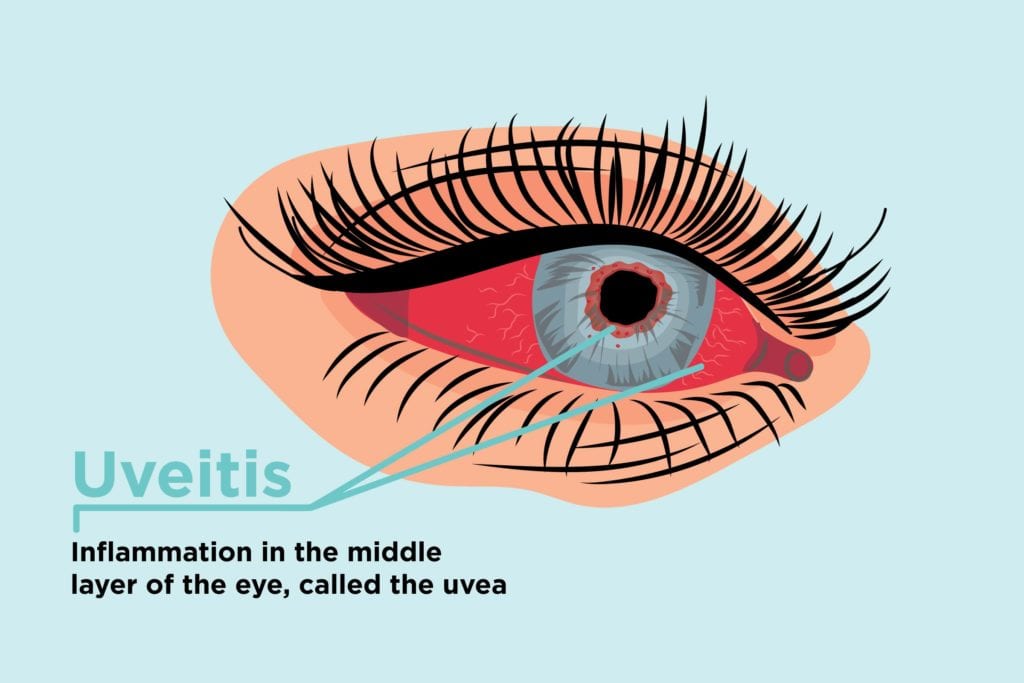

What Is Uveitis?

Uveitis means inflammation (the phrase “itis” denotes inflammation) that primarily affects the uvea, the middle layer of your eye, says New York-area ophthalmologist Marc Werner, MD. Uveitis (pronounced you-vee-EYE-tis) produces swelling in the eye and can destroy eye tissue over time if left untreated.

The uvea contains many of the eye’s blood vessels, which is a way that inflammatory cells from the immune system enter the eye and start causing damage. The uvea is located between the inner layer of the eye (the retina) and the outer white layer of the eye (the sclera). The uvea contains the following parts of the eye:

- Iris: the colored part of the eye

- Ciliary body: between the iris and the choroid; helps the eye focus and provides nutrients to the lens

- Choroid: contains a network of blood vessels that provides nutrients to the retina

There are three basic types of uveitis and they’re based on where in the uvea inflammation occurs, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Anterior uveitis occurs in the front of the uvea, or the iris. It tends to start suddenly. Some types of anterior uveitis are ongoing; others can come and go.

- Intermediate uveitis occurs in the middle of the uvea, or the ciliary body. Symptoms can last for weeks to years. This type of uveitis tends to recur cyclically.

- Posterior uveitis occurs in the back of the uvea, or the choroid. Symptoms can develop over time and last for years.

Some people can experience uveitis in more than one part of their eye.

What Causes Uveitis?

Uveitis is caused by inflammation in the eye. About half the time, doctors can’t identify what’s causing the inflammation, says Dr. Werner. For the other half of patients, uveitis can be caused by:

- An autoimmune disease like arthritis or ulcerative colitis

- Infection in the eye or elsewhere in the body

- Bruises or toxins in the eye

Sometimes people get uveitis after they’ve already been diagnosed with an autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis; in other cases, eye problems might be an early symptom that helps you get diagnosed with inflammatory arthritis.

Who Gets Uveitis?

According to the National Eye Institute, uveitis primarily affects people between 20 and 60, but it can occur at any age. One study, based on medical records of people in California, suggests that around 280,000 people are affected by uveitis each year.

What Are Common Symptoms of Uveitis?

The main symptoms of uveitis are:

- Redness in the eye

- Pain in the eye

- Decreased vision, blurry vision, or floaters

- Light sensitivity

“Typically uveitis is more of a deep pain, and you’ll feel very, very light sensitive,” says Dr. Werner. But milder cases might be easier to ignore or to delay seeking care for.

“Uveitis may not always feel different from everyday eye irritation,” says uveitis specialist Purnima Patel, MD, a clinical spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology and associate professor of ophthalmology at the Emory Eye Center. “It’s important to come in so the doctor can examine your eyes under the microscope and see what’s going on.”

If your eye symptoms are not going away, getting worse, or feel more severe or different than something you’ve experienced in the past, that’s a sign you should see an eye doctor for evaluation, says Dr. Patel.

How Is Uveitis Diagnosed?

“The majority of the time, uveitis is easy to diagnose,” says Dr. Patel.

If a patient comes in complaining of pain, redness, and light sensitivity, the eye doctor will likely suspect it could be uveitis. They will use the biomicroscope — “where you put your chin in that instrument and your doctor can look at the front and back of the eye,” says Dr. Werner — to look for evidence of inflammatory cells floating in your eye.

Then your doctor will ask questions about your medical history and other symptoms to try to assess what’s causing the uveitis.

“The rule of thumb is, if an adult comes in, you take a history — do you have back pain, you look at their joints, their hands, do you have any arthritis?” says Dr. Werner. If they have none, he says, you typically just treat the uveitis symptoms (more on that below). “Every adult is entitled to one episode of uveitis before you do a workup,” he adds.

But if you have anything in your medical history that suggests you could have an autoimmune disease (like arthritis, lupus, or multiple sclerosis) or an infection (like tuberculosis, syphilis, or shingles), your eye doctor may order more testing or refer you to another specialist.

According to the AAO, additional testing could include:

- Physical exam

- Bloodwork

- Imaging such as X-rays

- Examination of eye fluids

How Is Uveitis Treated?

Treatment of uveitis is critical to prevent long-term damage.

“If you let inflammation persist in the eye, it’s going to lead to all sorts of problems,” says Dr. Werner. “You can get glaucoma from the inflammation and have permanent loss of vision from that. You can get a type of scarring where the iris, the colored portion of the eye, sticks to the lens of the eye, and that can also lead to decreased vision and further problems.”

The mainstay of uveitis treatment is steroids to stop the inflammation, says Dr. Patel. “Treatment will depend on the part of the eye where the inflammation is, how severe it is, and what else is going on in the body,” she says.

Typically, doctors will start with steroid eye drops; they may be prescribed for two to three weeks and then tapered off as symptoms start to improve. However, Dr. Werner notes, if the uveitis symptoms return as the drops are tapered, then you have to start the medication again.

For more serious cases of uveitis or those that aren’t responding well to the eye drops, doctors may recommend steroid injections into the eye or oral steroid pills.

You may also be prescribed eye drops to dilate your pupil and relieve the pain that’s accompanying the uveitis.

“The goal of uveitis treatment is to make the disease inactive with the least amount of medication needed,” says Dr. Patel.

That’s because using steroids for longer periods of time has its own side effects, including increased risk of high blood sugar, blood pressure, glaucoma and cataracts, osteoporosis, and infections.

Treatment for uveitis also includes considering the underlying cause. If you have an autoimmune disease, making sure that it’s well controlled with disease-modifying drugs will also help treat your uveitis. Antibiotics or antiviral medications will likely be prescribed to treat an infection that’s causing uveitis.

It’s very important to follow your doctor’s instructions for treating your uveitis to avoid complications.

What Does Uveitis Say About Your Arthritis Disease Control?

If you know you have uveitis and an autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis, it’s important that your eye doctor and rheumatologist are in touch.

“Sometimes uveitis can be an indication that the disease-modifying drug needs to be changed,” says Dr. Werner. “It depends how severe the uveitis is. Some patients need to be chronically on eye drops, even as infrequently as one drop every other day, just to make sure that their eye doesn’t flare up.”

If you get a case of uveitis, or start getting it more frequently, your rheumatologist may want to do blood tests to check markers of inflammation, such as the sedimentation rate. If they see inflammation is creeping up — which can trigger the uveitis — they may want to change your arthritis treatment plan.

And if you have uveitis and you’ve never been diagnosed with an autoimmune disease, it’s important to let your eye doctor know if you have any other symptoms of pain or swelling elsewhere in the body.

“I had one patient who had inflammation in his eye and no idea what it was caused by,” says Dr. Werner. “When I asked him if he had any back pain, he said, ‘Yeah, because I fell down the stairs 20 years ago.’ I sent him to a rheumatologist and it turned out he tested positive for the HLA-B27 gene and had ankylosing spondylitis. Now he’s on medication to treat it. He’s grateful that we made that diagnosis and improved his other symptoms.”