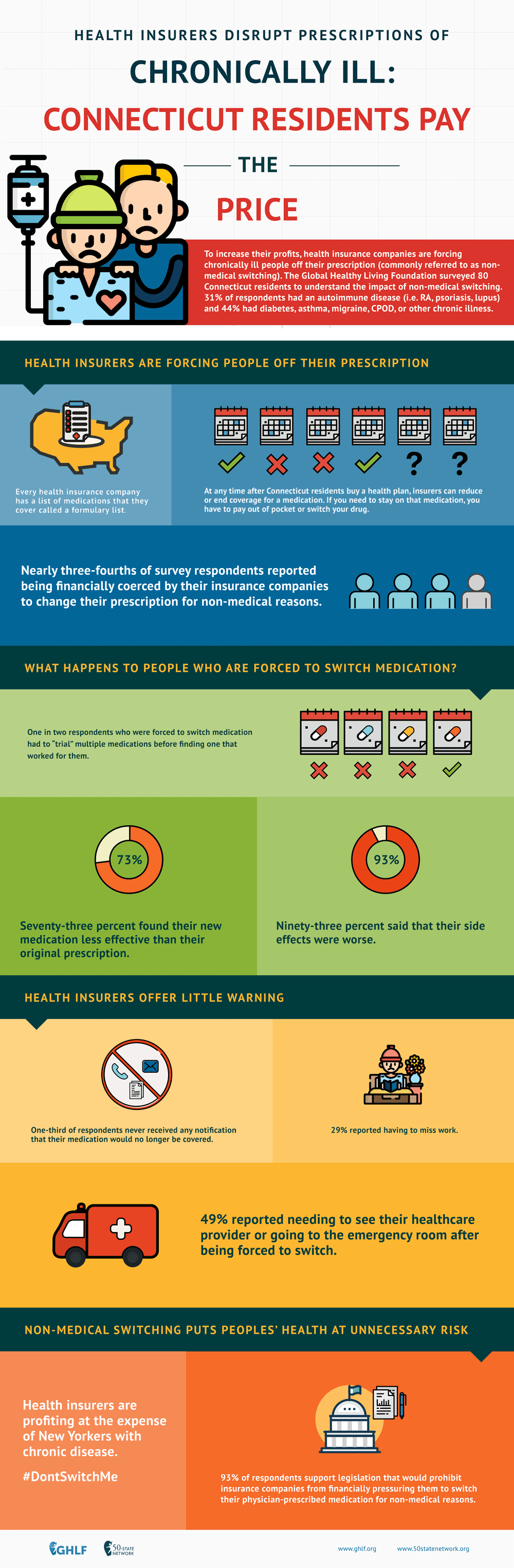

Connecticut Patient Sentiment Toward Non-Medical Drug Switching

Background

Although formularies and other utilization management techniques may help contain costs for third-party payers, potential savings often come at the expense of patients’ health. One major example is non-medical switching, which occurs when a health plan’s formulary changes in a way that monetarily pressures patients to cease filling their prescribed medication in lieu of a “preferred” or cheaper drug. Non-medical switching can occur during the health plan year. Formulary changes may include:

- Completely removing a patient’s medication from the formulary

- Increasing the patient’s out-of-pocket costs

- Changing the tier of the patient’s drug or adding new restrictions on the medication

Formulary changes can happen at any time. Insurers are free to change formulary coverage however they wish, whenever they wish. Changes often occur mid-year and it is important to understand that patients cannot renegotiate their contracts mid-plan and therefore have no choice but to stay with the plan. Essentially, patients are not being provided with the benefits that were marketed to them during the open enrollment period.

Whatever form it takes and whenever it occurs, non-medical switching can be very harmful to patients. As a result of being switched from their original, clinician-prescribed medication, patients may experience additional side effects, symptoms, disease progression, and potentially relapse. Beyond the immeasurable impact of this unnecessary suffering, the negative effects of non-medical switching can result in additional medical appointments, emergency room visits and even hospitalization, thereby actually increasing overall healthcare utilization costs.

Despite this, the impact of non-medical switching on patients has been remarkably unmeasured and ignored by health insurance and pharmacy benefit management companies. In order to better understand how Connecticut patients are affected by this harmful utilization management technique, Global Healthy Living Foundation (www.ghlf.org) conducted a survey of Connecticut residents living with chronic diseases. The survey’s aim was two-fold in measuring:

- The prevalence of Connecticut residents who are living with chronic diseases being pressured to switch from their clinician-prescribed medicine for non-medical reasons

- The adverse physical, mental, emotional, and productivity impact of non-medical switching

Methodology

In March 2018, GHLF partnered with a patient coalition, which consisted of 16 diverse patient and clinician advocacy organizations representing hundreds of thousands of residents in Connecticut living with chronic illness and their care providers. GHLF and the patient coalition invited Connecticut residents living with a chronic or rare illness to complete an online, 38-item survey that investigated patient experiences with the manipulation of their respective health plans’ formularies. In order to complete the survey, eligible respondents had to be:

- Diagnosed by a physician with a chronic or rare disease

- Currently living in Connecticutk

Prospective respondents who did not meet these two eligibility criteria were disqualified and prevented from completing the survey.

Executive Summary of Results

A total of 240 people started the online survey. Of the 240 participants, 98 did not complete the survey and 62 were disqualified for either not having a chronic or rare disease or for not being a Connecticut resident. The total number of participants who completed the survey is 80; only completed responses were analyzed.

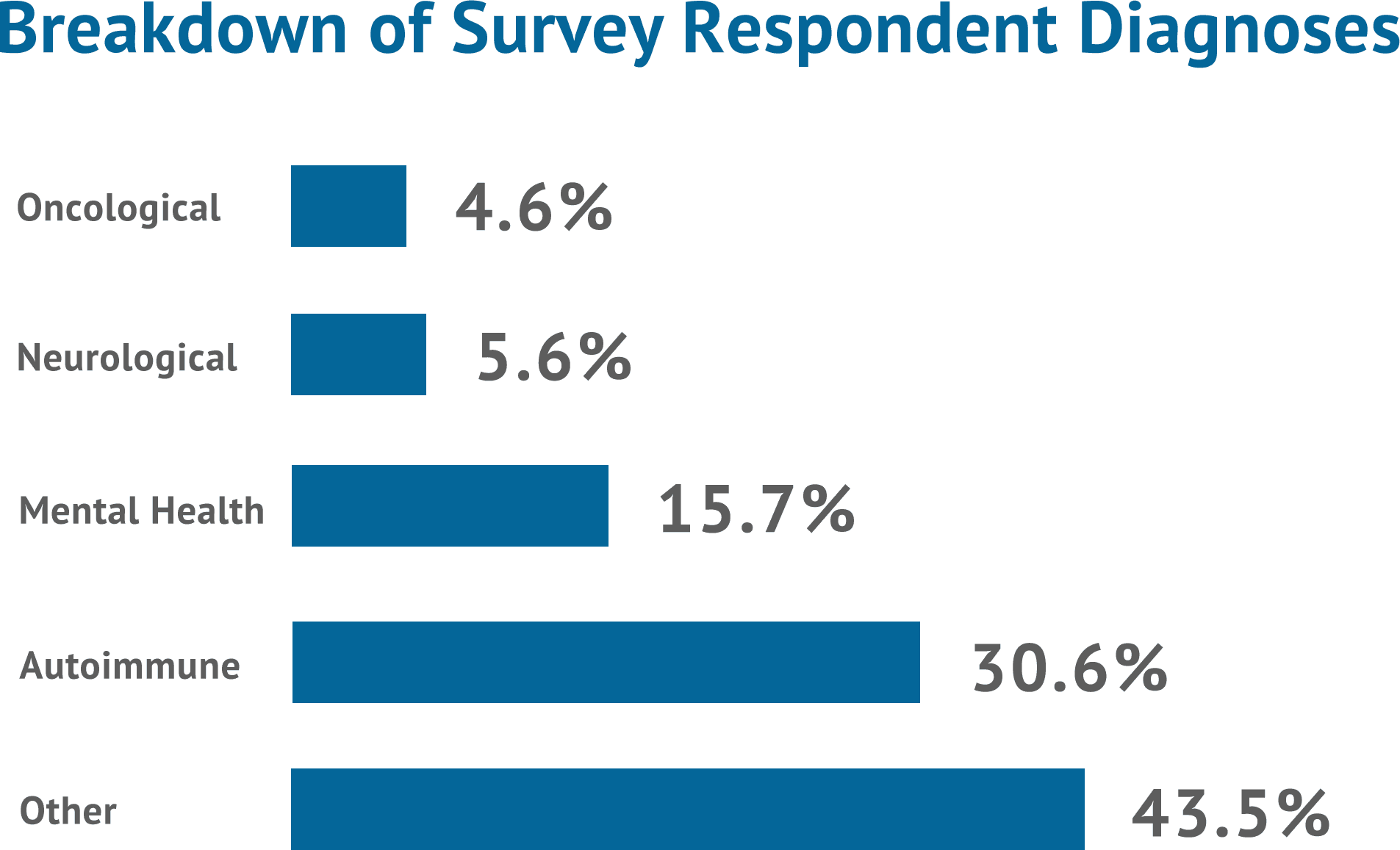

Although respondents’ individual diseases varied widely, five separate major classes were represented: autoimmune (30.6%), mental health (15.7%), neurological (5.6%), oncological (4.6%) and other (43.5%). A majority were female (93.8%), white (91.3%) and college educated (66.3%). More of the participants were unemployed (61.3%) than were employed (38.9%), either full-time, part-time, or self-employed. The majority of participants (53.8%) reported having a household income of $50,000 or less per year. In terms of health insurance, 44.8% of participants have Medicare and/or Medicaid, 45.8% have private insurance, and 9.4% have an ‘other’ form of insurance. None of the participants claim to not have health insurance.

How many patients does non-medical switching negatively impact?

Results of this survey show that it is commonplace for chronic and rare disease patients in Connecticut to experience sudden decreases in prescription-medication coverage. Over two-thirds (68.8%) reported that their insurance company switched their medication to a drug that was different from the one their physician prescribed as the result of a formulary change.

As much as 67.3% of those patients did not have the opportunity to reject and/or decline the medication switch. In addition to forced switches, mid-year changes in insurance coverage have been found to be so dramatic that four out of five participants (81.3%) reported that the primary therapy prescribed to them became suddenly and significantly more expensive to obtain. The vast majority of respondents (94.1%) reported now paying more out-of-pocket for their prescribed medication, with 76.5% reporting to pay a lot more.

Overall, effectively three-fourths (73.8%) of our survey respondents reported being financially coerced by their insurance companies to change their clinicianprescribed medication for non-medical reasons.

How does non-medical switching impact patients’ treatment and health?

Non-medical switching was shown to cause more than one in two (52.1%) of the survey respondents to trial multiple medications before finding another suitable drug that satisfactorily worked for them. A significant majority of respondents (72.9%) reported that they found their new medication to be less effective than the one they had previously taken.

Side effects were found to be a concern for patients who were non-medically switched. A majority of respondents (59.2%) reported experiencing them on their new medication. When asked to compare the side effects to their previous medication, 93.1% reported that the side effects were worse, with 55.2% reporting that they were much worse. No respondents reported their side effects being better, and only 6.9% reported the side effects staying about the same.

Of the people who did experience side effects, 48.9% reported seeing their healthcare provider, going to the emergency room, or both as a result of the complications they were experiencing. As much as 16.7% were hospitalized.

In addition, we aimed to assess some important ramifications associated with switching to a new or different medication for non-medical reasons. After sudden changes were made to patients’ prescription medication insurance coverage, 56.9% of respondents reported that their ability to obtain medication was delayed. A significant majority of respondents (72.9%) reported that the medication they switched to worked somewhat worse or much worse than the original prescribed medication. About a third (29.2%) of the respondents reported having to miss work as a result of reactions or complications stemming from their condition after they were forced to switch, and 54.2% reported that their ability to spend time with their family or loved ones was worsened.

Do insurers properly communicate formulary changes to patients?

When investigating communications by third-party payers to inform patients about formulary changes, our survey found that over one-third (35.0%) of all respondents reported never receiving any notifications, such as letters, emails, or phone calls, communicating details of their plan’s formulary or changes being made to it.

When respondents experienced alterations to their plan’s formulary, only 41.8% reported their insurance company informed them of the altered coverage to their prescribed medication. A little less than half of respondents (45.5%) were informed by their pharmacist, and a smaller percentage (9.1%) was informed by their physician.

How do patients feel about non-medical switching?

Nearly all respondents (92.5%) support legislation that would prohibit insurance companies from financially pressuring them to switch their physician prescribed medication for non-medical reasons.

When asked how important the out-of-pocket price of medication is in making a decision to use medication, 90.0% reported that it is either important or extremely important. As much as 65.0% of respondents said that it is extremely important. No respondents reported that it is either unimportant or extremely unimportant, and only 5.0% reported that it was neither important nor unimportant.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDED POLICY ACTION

Our survey has shown that non-medical switching is a prevalent and growing practice in Connecticut. It can put patients who have complex, chronic, or rare diseases at severe risk. Multiple switches can either force patients onto less effective medications for them or eliminate treatment options for patients in a disease state that has a limited bank of therapies. Health insurance companies’ utilization management techniques, such as reductions in drug coverage, result in treatment gaps and cessation of effective therapy, which often takes years to find. As a result of associated increases in side effects and adverse reactions that can lead to hospitalization, more doctors’ appointments, emergency room visits, and so on, nonmedical switching can actually increase overall utilization costs.

Currently, there are no state protections for patients in Connecticut from mid-year and year-to-year formulary coverage changes. Connecticut needs legislation to ensure that insurers honor their contracts with patients and prioritize the value of treatment stability; protecting the health of patients. Legislation should consist of patient protections that guarantee that at an absolute minimum, outside of open enrollment periods, a health insurance entity providing commercial health insurance coverage for prescription drugs shall not:

- (a) Remove any covered prescription drug from its list of covered drugs during the health plan year unless the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a statement about the drug that calls into question the clinical safety of the drug, or the manufacturer of the drug has notified the FDA of any manufacturing discontinuance or potential discontinuance as required by s.506C of the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. s 356c;

- (b) Reclassify a drug to a more restrictive drug tier or move a drug to a higher cost-sharing tier during the health plan year unless a generic equivalent product becomes available; or

- (c) Reduce the maximum coverage of prescription drug benefits.