Osteoarthritis is known as the “wear and tear” form of arthritis that breaks down the joints and surrounding tissue. It most often affects the joints in the hands, hips, knees, lower back, and neck. Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis — it’s thought to affect more than 527 million people worldwide — and often comes along with getting older as well as other risk factors.

Where osteoarthritis affects your joints, osteoporosis is a condition that impacts your bones. It causes bones to become weak, brittle, and break more easily. This bone condition is also common: Osteoporosis is thought to affect over 200 million people across the globe.

If you have osteoarthritis, chances are you’re already taking steps to protect your joints. But here’s why you should find ways to preserve bone health, as well.

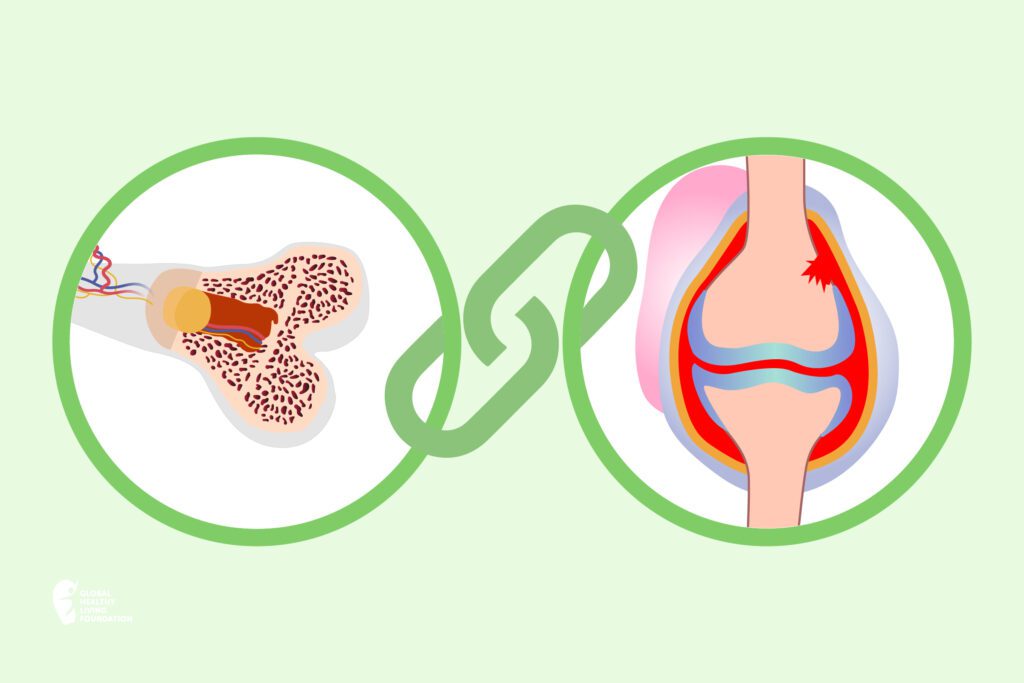

The Link Between Osteoarthritis and Osteoporosis

The relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis has been studied for decades. That said, there’s still a lot we don’t fully understand.

In some ways, they’re very different, says Nancy E. Lane, MD, Endowed Professor of Medicine and Rheumatology, and Director for the Center for Musculoskeletal Health at the University of California Davis School of Medicine.

Because osteoporosis is a disease that weakens the bones, it often leads to fractures. “With osteoporosis, the pain is, for the most part, trauma induced,” she says. “Osteoarthritis is more of a degenerative disease where, as the cartilage wears out, it hurts just to use your joints.”

That said, it’s possible to have both osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. And the two conditions do have a few factors in common.

Age

The main thing osteoarthritis and osteoporosis have in common? “They’re two age-related diseases,” says Lane.

While osteoporosis can develop at any age, the risk of osteoporosis increases in people over age 50. That’s because bone mineral density and bone mass both tend to decrease with age. This can impact the structure and quality of the bones, which increases the risk for bone fracture.

The risk of developing osteoarthritis also increases with age. People who are 50 and older are more likely to develop osteoarthritis, after years of wear and tear on the joints.

Sex

Both osteoarthritis and osteoporosis are more common in women than men.

One common underlying factor? Hormones. Research shows that the decrease in estrogen that occurs with menopause can increase the risk of osteoarthritis. Estrogen deficiency in menopause has also been proven to play a role in the development of osteoporosis.

“Men get both [osteoporosis and osteoarthritis] too, but their osteoporosis shows up later in life — usually after the age of 70,” says Lane.

Biomarkers

It’s unclear if there’s a biological link between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. “There may be, but it’s a little on the subtle side,” says Lane.

Some research has found that osteoarthritis and osteoporosis may share certain biomarkers or indicators that contribute to both conditions. Though more studies are needed to fully understand this link.

Impact

When it comes to impact, both conditions can take a similar toll. Research suggests that osteoporosis and osteoarthritis can lead to increased pain, disruptions in social life, and an overall reduced quality of life.

Severity may also play a role. Research shows that more severe cases of osteoarthritis that come with limited mobility along with increased pain may accelerate bone loss and lead to osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis Risk Factors

Aside from age and sex, many other risk factors may also play a role in the development of osteoporosis. These can be broken into two groups: uncontrollable and controllable risk factors.

By familiarizing yourself with the many risk factors tied to osteoporosis, you can have an informed conversation with your health care provider about your personal risk and what you can do to protect your bones.

Uncontrollable risk factors for osteoporosis include:

- Gender: Osteoporosis is more common in women, especially in perimenopausal women.

- Ethnicity: Osteoporosis is more common in Caucasian and Asian women.

- Age: The older you get, the higher your risk of developing osteoporosis.

- Family history: If an immediate family member (like a parent) has osteoporosis, your risk of developing it increases.

Controllable risk factors, or those you can modify, include:

- Medications: Long-term use of steroids or anticonvulsants can contribute to osteoporosis.

- Diet: Low calcium and vitamin D intake may contribute to osteoporosis risk.

- Inactivity: Not exercising regularly, or being inactive, can weaken your bones.

- Weight: Being underweight (or having a small body frame) can impact bone health.

- Smoking: Smoking cigarettes makes you more prone to osteoporosis and bone fractures.

- Alcohol: Excessive alcohol consumption impacts how the body absorbs calcium and vitamin D, both of which are critical for healthy bone development.

Osteoporosis Symptoms

Osteoporosis is sometimes referred to as a “silent” condition. That’s because it often has no symptoms.

As it progresses, it can lead to symptoms like

- Back pain

- Sudden back pain

- Joint pain

- Changes in posture

- Stooping or loss of height

But most people aren’t aware they have osteoporosis until they fracture or break a bone. That’s why it’s so important to be aware of osteoporosis and take steps to protect your bone health.

Tips to Manage Osteoarthritis and Protect Your Bones

These strategies can help you manage osteoarthritis and keep bones healthy.

Eat a Healthy, Nutritious Diet

Research shows that poor dietary habits can contribute to the progression of osteoarthritis — but following healthier eating habits may help decrease disease progression.

While there’s no one diet to promote bone and joint health, plan to eat a well-balanced diet full of fruits, vegetables, fish, whole grains, and legumes. Also, aim to get plenty of calcium and vitamin D — which can be found in dairy products like milk, cheese, and yogurt — to help preserve bone strength.

Calcium reduces bone loss and decreases the risk of fracturing the vertebrae. Women who have not gone through menopause and all men should consume at least 1,000 mg of calcium per day, while woman who have gone through menopause should consume 1,200 mg of calcium per day. It is important to keep in mind that you should not consume more than 2,000 mg of calcium due to risk of having side effects such as kidney stones in certain individuals who take calcium supplements and other less severe side effects such as constipation, indigestion, and possible interactions with your other medications.

Vitamin D helps our body absorb calcium and is normally made in the skin after exposure to sunlight. You can also get vitamin D through a healthy diet and by taking supplements. The current recommendation is that men over 70 years and women who have gone through menopause consume at least 800 international units (20 micrograms) of vitamin D per day. Any type of milk that has a label saying “vitamin-D fortified” contains 100 international units of vitamin D per glass (8 oz/ 250 ml). Lower levels of vitamin D are not as effective, while high doses can be toxic, especially if taken for long periods of time.

Consult your health care professional before taking any supplements.

Stay Active

“Exercise strengthens the muscles around your joints, which can prevent pain,” says Lane. Try to incorporate a mix of strengthening, cardio, balance, and stretching exercises into your overall fitness routine for optimal results. Talk to your health care provider before starting a new exercise regimen.

Research has found that resistance exercises in particular — such as weightlifting — can help preserve bone health and muscle mass. However, low-impact exercises — like walking or riding a bike — are best for people who have osteoarthritis, as they don’t overtax the joints.

Maintain a Healthy Weight

Being overweight can tax joints affected by osteoarthritis. Being underweight can weaken bone health and increase your risk of osteoporosis. Aim to reach and maintain a healthy weight to promote optimal joint and bone health.

However, if you need to lose weight, proceed with caution. Research published found that, depending on your age, implementing a low-calorie diet for weight loss may decrease bone mass. That said, any long-term effects that weight loss may have on bone health are not yet fully understood. Newer research published in 2018 found that the benefits weight loss can have on your overall health may outweigh the risks of lowered bone mineral density.

Quit Smoking

Smoking is bad for your health in many ways—including bone and joint health. Smoking can contribute to weakened bones and increase fracture risk. What’s more, many people who smoke also partake in other unhealthy lifestyle habits that affect bone health, like decreased activity levels and poor diet.

If you smoke, quitting can improve your overall health and your bone health. Findings from one study show that quitting may help increase bone mass previously lost due to smoking.

Ask your doctor if you need help with quitting. You may benefit from the use of a smoking cessation aid.

Moderate Alcohol Use

Moderate alcohol use has been thought to have protective benefits when it comes to preventing osteoarthritis. However, newer evidence suggests this may not be the case.

Research also shows that chronic, excessive alcohol consumption increases osteoporosis risk. What’s more, heavy drinking has been linked with a decrease in bone density and weakened bones. Additionally, those who drink alcohol excessively are also more likely to partake in other unhealthy lifestyle habits that affect bone health, including smoking and poor eating habits.

For some people, alcohol consumption is not safe. If you are able to drink alcohol, be sure to so in moderation: That means one drink a day (or less) for women, and two (or less) for men.

When to Talk to Your Doctor About Bone Health

Because there are often no symptoms of osteoporosis until a bone breaks, routine screening can help prevent osteoporosis. Screening is easy and only takes five to 10 minutes. Early detection can help you take proper steps to prevent fractures and promote bone health.

Routine screening for osteoporosis should be done:

- After age 65 for women, 70 for men, or sooner depending on your personal risk factors

- Every one or two years, or more often depending on your health

- After a bone fracture in those over age 50

- When taking new medication associated with low bone mass or bone loss

Talk to your doctor at your next health exam about getting screened for osteoporosis.

This article was made possible with support from Amgen.

Alswat, Khaled A. “Gender Disparities in Osteoporosis.” Journal of Clinical Medicine Research. 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2970w.

Atik, O, et al. “The Role of Biomarkers in Osteoarthritis and Osteoporosis for Early Diagnosis and Monitoring Prognosis.” Joint Diseases and Related Surgery. August 1, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.5606/ehc.2019.004.

Bone health: Tips to keep your bones healthy. Mayo Clinic. March 6, 2021.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/bone-health/art-20045060

Choksi P, et al. (2018). Weight loss and bone mineral density in obese adults: a longitudinal analysis of the influence of very low energy diets. Clinical Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-018-0063-6.

Evaluation of Bone Health/Bone Density Testing. Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation.

https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/patients/diagnosis-information/bone-density-examtesting/.

Food and Your Bones — Osteoporosis Nutrition Guidelines. Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation. https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/patients/treatment/nutrition/.

Get the Facts on Calcium and Vitamin D. Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation. https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/patients/treatment/calciumvitamin-d/get-the-facts-on-calcium-and-vitamin-d/.

Hame SL, et al. (2013). Knee osteoarthritis in women. Current Reviews in Musculoskeleton Medicine. June 2013. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-013-9164-0.

Hong AR, et al. Effects of Resistance Exercise on Bone Health. Endocrinology and Metabolism. November 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2018.33.4.435.

How Often Should I Get Tested? American Bone Health. https://americanbonehealth.org/bone-density/how-often-should-i-have-a-bone-density-test/.

Interview with Nancy E. Lane, MD, Endowed Professor of Medicine and Rheumatology, and Director for the Center for Musculoskeletal Health at the University of California Davis School of Medicine.

Kaussar NN, et al. A Review on Osteoarthritis and Osteoporosis: Ongoing Challenges for Musculoskeletal Care. International Journal of Care Scholars. 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.31436/ijcs.v2i2.127.

Kiyota Y, et al. Smoking cessation increases levels of osteocalcin and uncarboxylated osteocalcin in human sera. Scientific Reports. 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73789-4.

Long H, et al. Prevalence Trends of Site-Specific Osteoarthritis From 1990 to 2019: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Arthritis & Rheumatology. July 2022 doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42089.

Osteoporosis Exercise for Strong Bones. Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation. https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/patients/treatment/exercisesafe-movement/osteoporosis-exercise-for-strong-bones.

Osteoarthritis (OA). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 27, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/osteoarthritis.htm.

Osteoporosis. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteoporosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351968

Osteoporosis. National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/osteoporosis. June 26, 2017.

Osteoporosis. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/osteoporosis

Smoking and Bone Health. NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center. https://www.bones.nih.gov/health-info/bone/osteoporosis/conditions-behaviors/bone-smoking.

Sampson HW. Alcohol and Other Factors Affecting Osteoporosis Risk in Women. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh26-4/292-298.htm.

Schafer AL. Decline in Bone Mass During Weight Loss: A Cause for Concern? Journal of Bone Mineral and Research. 2015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2754.

Stamenkovic BN, et al. Is Osteoarthritis Always Associated with Low Bone Mineral Density in Elderly Patients? Medicina. 2022. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58091207.

To K, et al. The association between alcohol consumption and osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of observational studies. Rheumatology International. 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04844-0.

Wang X, et al. 2021. Alcoholism and Osteoimmunology. 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.2174/1567201816666190514101303.

Xu C, et al. Dietary Patterns and Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz333.