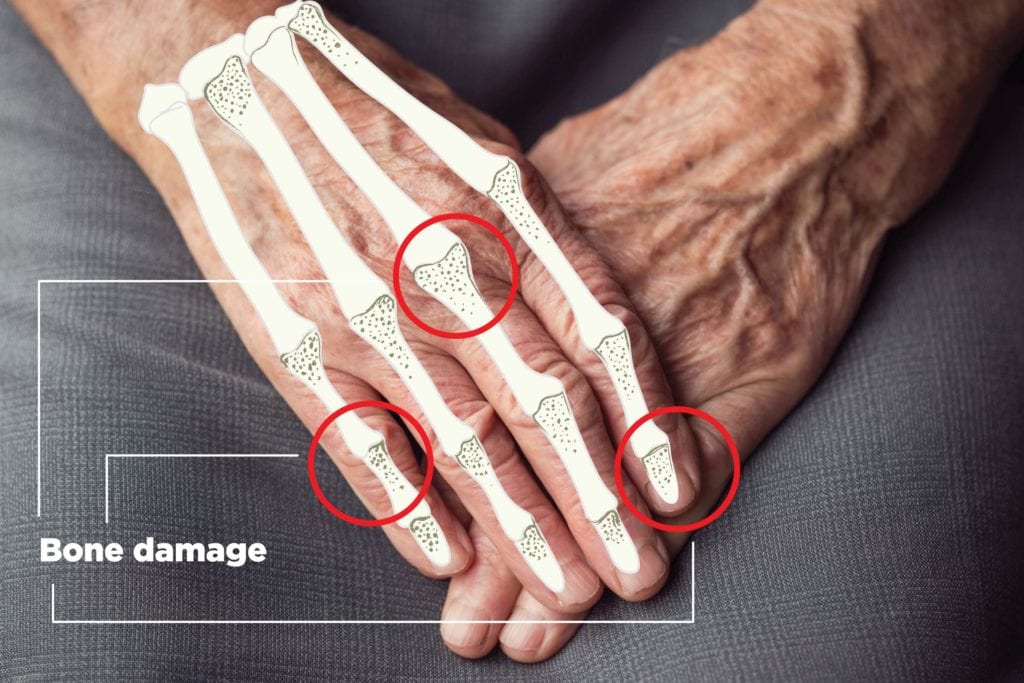

If you have psoriatic arthritis (PsA), you’re well aware of the way the inflammatory disease can affect your skin (red, silvery, scaly patches) and your joints (stiffness, swelling, and pain in any of the body’s joints — knees, shoulders, neck, back, finger and toes), but you might not know as much about how psoriatic arthritis can damage your bones.

PsA is an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system attacks both the joints and skin (as opposed to just affecting the skin, in the case of psoriasis). About 30 percent of people with the skin disease psoriasis also develop psoriatic arthritis.

A new German study published in the journal Arthritis Research & Therapy sought to examine how different kinds of bone damage occur in people with both psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis, to better understand what kind of underlying mechanisms these disease share when it comes to causes of bone damage.

Researchers used a new form of imaging called high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT), which can look at bones in 3D. It allows doctors to see bone density and fragility more accurately than traditional bone scans.

Bone Erosion in Psoriatic Arthritis and Psoriasis

In one part of the study, the researchers looked at how age affects the level of bone erosion in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis.

They found that the youngest PsA patients (20 to 40 years old) had a similar number of erosions in their dominant hand (1.05) as did a control group of healthy people without PsA. But psoriatic arthritis patients older than 60 had an average erosion of 2, almost double that of the younger group.

This suggests that “age is a key determinant of erosive damage in the joints,” according to the study authors.

People with PsA had more erosions (1.4) than did those with psoriasis (0.5). In fact, there weren’t significant differences in the amount of erosive bone damage in people with psoriasis and healthy controls.

Bone erosions occur as a result of both inflammatory and mechanical damage to bone and joints. People without inflammatory joint disease — such as healthy people and those with only psoriasis — most likely experience this kind of bone damage from mechanical wear and tear, but “in patients with PsA, the additional inflammatory trigger appears to speed up erosions,” the researchers told MedPage Today.

In other words, bone erosion appears to be more of an issue for psoriatic arthritis patients than for those with only psoriasis. People with psoriasis don’t appear to be at greater risk for bone erosion than the general population.

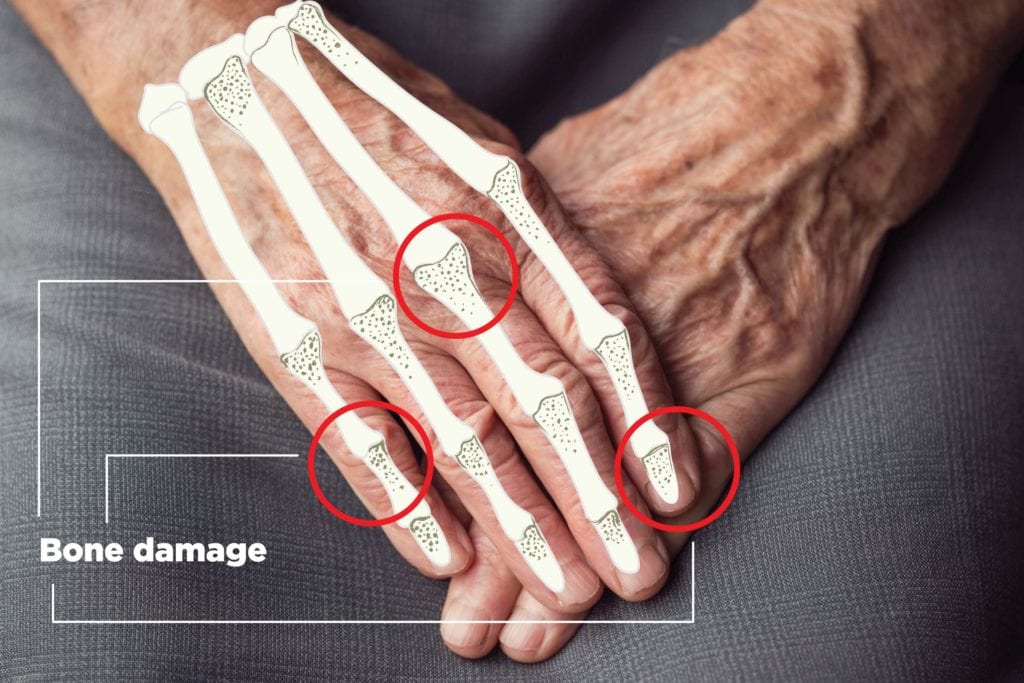

Bone Spurs and Psoriatic Arthritis and Psoriasis

The study authors also wanted to understand how bone spur growth compares in people with psoriatic arthritis and those with psoriasis. These bone formations, called enthesiophytes, occur where tendons attach to bones. They can make it painful to move and cause even more inflammation in joints, since the bone is now protruding in places it shouldn’t be.

Bone spurs have also been detected in patients with psoriasis, which suggests that psoriasis and PsA share some underlying effects on bone, according to MedPage.

The researchers detected 9.5 enthesiophytes in the hands of people with PsA, compared with 5.6 among people with psoriasis. The spurs were also larger in people with PsA than in those with only psoriasis.

The degree of bone spurs in people with both psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis was less tied to age, and more related to how long people have had their disease.

Since bone spurs were also found in patients with psoriasis — which precedes the development of psoriatic arthritis in most PsA patients — the researchers suggest more studies are needed to see if the development of bone spurs in psoriasis can help predict the onset of psoriatic arthritis.

How to Protect Your Bones with Psoriatic Arthritis and Psoriasis

The findings from this study emphasize how important it is to monitor your psoriasis and make sure you seek treatment if you think you’re starting to show symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. Early detection and treatment may delay bone erosion and bony spur development.

In addition to staying on top of your condition and seeing a specialist for a treatment plan, here are other ways to protect your bones:

Manage your weight: The researchers noted that that the groups of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis patients in this study had a higher BMI than those in the control group. Excess weight can cause added pressure on joints, exacerbating inflammation and pain.

Assess your calcium intake: Calcium is an important mineral for maintaining bone health. Making sure you get enough calcium from your diet (as well as from supplements, if your doctor advises) can help strengthen your bones against fractures. Research shows people with psoriatic arthritis are more susceptible bone fractures.

Add weight-bearing moves to your exercise regimen: If your primary forms of exercise are swimming or biking, you’re missing a chance to bolster your bone health. Weight-bearing exercises are those that force your body to work against gravity. These include walking, jogging, dancing, and sports like tennis and basketball. Swimming can be especially soothing when you’re dealing with an arthritis flare, but aim to include weight-bearing exercise in your schedule regularly.

Want to learn more?

Listen to this episode of Getting Clear on Psoriasis, from the GHLF Podcast Network.