Learn more about our FREE COVID-19 Patient Support Program for chronic illness patients and their loved ones.

A new SARS-CoV-2 (coronavirus) variant that spreads more easily — and is quickly replacing other strains of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 — was first detected in the United Kingdom in September. This mutation is believed to have originated in an immunocompromised patient.

You might be understandably worried if you’re seeing “immunocompromised” and “virus mutations” in the same headlines, especially if you take immunosuppressant drugs for a chronic condition such as inflammatory arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, or lupus.

While more research is needed — and everyone’s vulnerability to COVID-19 and complications are unique based on their medical conditions and medications — there likely isn’t a great deal of concern that people with autoimmune or inflammatory conditions are more at risk for coronavirus mutations or new strains.

Here is more information about new coronavirus variants and their connection to immunocompromised patients so far — and what it means for you if you live with a rheumatic or inflammatory disease.

Why Is the SARS-CoV-2 Virus (Coronavirus) Mutating?

To start, it’s important to understand how viruses replicate in the body — and how those replications can turn into new strains of the virus. Viruses replicate in their host in order to keep spreading and surviving.

When viruses replicate, changes from the original version are naturally created. It’s kind of like if you were to re-type an entire report for school or work, you’d probably introduce a couple of typos along the way.

Like many other viruses, the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 is known as an RNA virus. That means its genetic material is encoded in ribonucleic acid (RNA). This is different from our human genetic material, which is enclosed in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

RNA from the coronavirus tricks your body into believing it is made by your own DNA, which allows it to be replicated in your body, per the University of Rochester.

“All viruses mutate, but RNA viruses are prone to having errors just by the nature of their replicative process,” says Sydney Ramirez, MD, PhD, an infectious disease doctor and researcher at the University of California San Diego and La Jolla Institute for Immunology. “They’re more error-prone than, for example, the DNA polymerases [enzymes] we have in our own cells that make copies of our DNA.”

RNA enzymes don’t “proofread” their work as well as DNA enzymes when they reproduce — leading them to create more mutations. This is why you’ll find multiple versions of the virus within the same individual, regardless of their immune status.

When a virus mutates, it starts off as a random process. However, if there’s a mutation or set of mutations that make the virus more fit or more stable, it will often be replicated and prevail as the virus spreads through the population.

“That seems to be what’s happening here: These particular mutations that we’re seeing are actually allowing the virus to be more transmissible and spread more,” says Dr. Ramirez.

After all, it’s in a virus’s best interest to evolve in such a way that it can spread to more people.

What’s the Link with Coronavirus Mutations and Immunocompromised Patients?

Although more research is needed, experts believe that severely immunocompromised patients may give the SARS-CoV-2 virus a greater chance to mutate. The B.1.1.7 variation may have had a rare, long span of evolution in a chronically infected patient who transmitted the virus late in their infection.

“It’s simply too many mutations to have accumulated under normal evolutionary circumstances,” Stephen Goldstein, PhD, a virologist at the University of Utah, told Science. “It suggests an extended period of within-host evolution.”

In other words, perhaps the SARS-CoV-2 virus was able to evolve into its B.1.1.7 variation more successfully in a severely immunocompromised patient because their immune system could not fight off the virus, so it stuck around for a long period of time and had more opportunities to mutate.

Keep in mind that the term “immunocompromised” is quite broad and applies to vastly different medical conditions. Most of the research on COVID-19 viral mutations and immunocompromised patients has involved people who are severely immunocompromised — say, from cancer treatment or an organ transplant.

“Cancer patients who are being treated — particularly with chemotherapy and stem cell transplants — or organ transplant patients are also typically much more immunocompromised than patients with rheumatic diseases,” says Jeffrey Sparks, MD, MMSc, Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Here are three examples of cases in which viral evolutions were detected in severely immunocompromised patients. These cases do not include the original B.1.1.7 mutation, which is also suspected to have started in an immunocompromised patient.

Case 1: A Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

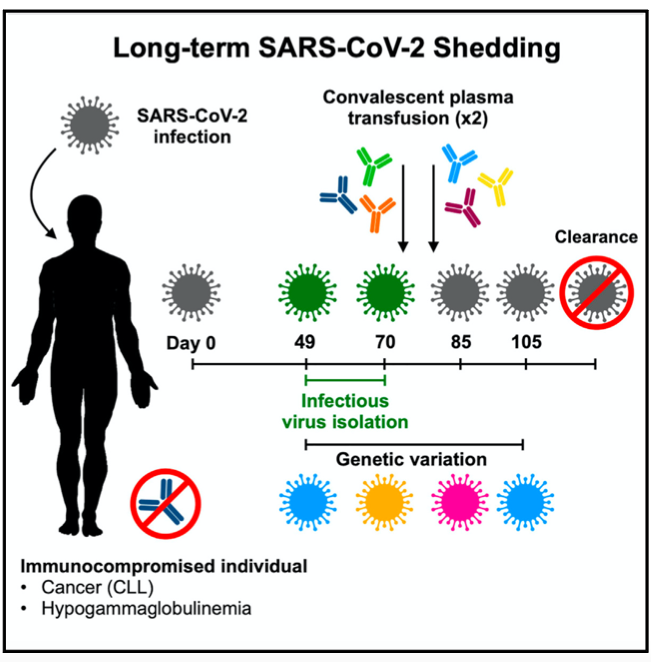

In one November 2020 case study published in the journal Cell, long-term SARS-CoV-2 shedding (meaning the virus was replicating in the body and may have been contagious to others) was found in the upper respiratory tract of an immunocompromised 71-year-old woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and acquired hypogammaglobulinemia, an immune system problem that results in a lower antibody count and an increased risk of infection.

That virus shedding was observed in the patient for 70 days after initial diagnosis, and virus RNA was observed for up to 105 days. It was not cleared after the first treatment with convalescent plasma (blood from recovered COVID-19 patients that contains antibodies). Several weeks after a second transfusion, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was no longer detected in the patient.

Researchers observed a genomic evolution of the virus — with continuous turnover of dominant viral variants — in this patient. However, they don’t believe these mutations played a role in how long the virus persisted because they didn’t find evidence of natural selection.

Natural selection occurs when a viral variant provides the virus with a benefit for survival and therefore becomes the dominant variant. In this patient’s case, the mutations did not affect the ability or speed of the virus to replicate.

Case 2: A Patient with Lymphoma

In another case, a COVID-19 patient who was being treated for lymphoma relapsed and was given the medication rituximab, according to a preprint analysis on medRxiv. Rituximab is used for a variety of diseases, including cancer and rheumatoid arthritis. It depletes B cells that normally produce antibodies. For this patient, it made it difficult for him to fight off the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Despite being given the antiviral drug remdesivir, the steroid dexamethasone, and antibody-containing convalescent plasma from recovered patients, the infected individual died 101 days after his COVID-19 diagnosis. Experts discovered several mutations that could have potentially helped the virus escape antibodies.

“Our study raises the possibility of virus evasion, particularly in immune-suppressed individuals where prolonged viral replication occurs,” note the authors. “Our observations represent a very rare insight, and only possible due to lack of antibody responses in the individual following administration of the B cell-depleting agent rituximab for lymphoma, and an intensive sampling course undertaken due to concerns about persistent shedding and risk of nosocomial transmission [infection that occurs in a health care setting].”

Case 3: A Patient with Severe Antiphospholipid Syndrome

In a third case reported in December in The New England Journal of Medicine, a 45-year-old man with severe antiphospholipid syndrome (an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system attacks normal proteins in the blood) who was receiving anticoagulation therapy, glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, and intermittent rituximab and eculizumab was admitted to the hospital with a fever. He was diagnosed with COVID-19, received a five-day course of remdesivir, and was discharged on his fifth day.

The patient quarantined at home from day six through day 68, but he was hospitalized three times for abdominal pain and once for fatigue and difficulty breathing during the quarantine period. On day 72, he tested positive for COVID-19 again, and went on to experience cellulitis and continued respiratory decline. On day 154, he died from shock and respiratory failure.

Researchers also found accelerated virus mutations in this patient. “Although most immunocompromised persons effectively clear SARS-CoV-2 infection, this case highlights the potential for persistent infection and accelerated viral evolution associated with an immunocompromised state,” note the authors.

Dr. Sparks is one of the authors of this case report, and also the doctor who treated this particular patient. He notes that this patient’s case cannot be generalized to apply to other immunocompromised patients.

“Not many patients are in this scenario. He had a very severe form of antiphospholipid syndrome that happened to be severely active at the time of COVID-19 infection,” says Dr. Sparks. “He also happened to have just received rituximab and started eculizumab [another immunosuppressive drug] right before he got infected, and he had a very severe, active inflammatory lung infection. Unfortunately, everything was set up for a bad outcome.”

The patient’s level of immunosuppression was likely more similar to someone who was being treated for cancer or an organ transplant given the amount of immunosuppression he had been receiving than someone with a typical rheumatic or inflammatory disease, adds Dr. Sparks.

Adults of any age who have conditions such as cancer or a weakened immune system from a solid organ transplant have an increased risk of severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19 — which refers to hospitalization, admission to the ICU, incubation or mechanical ventilation, or death, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Why Might Immunocompromised Patients Be Prone to Coronavirus Mutations?

If someone is sick with COVID-19 for a longer period of time because their body is unable to fight off infection, the coronavirus may have a greater chance to mutate through many replications.

“With each cycle of replication, there’s always a chance of error — so the more cycles the virus can replicate within an individual person or cell, the more chances there are for error,” says Dr. Ramirez. “Because of that, the longer the virus hangs around in the body before being cleared by the immune system, the greater the chances that it’s going to mutate.”

The part of your immune system that is affected can impact your risk of severe and chronic COVID-19. For example, take T cells: These are a type of white blood cells that develop from stem cells in the bone marrow, per the National Institutes of Health. T cells are part of the immune system and help protect the body from infection.

“We see that people who have T cell deficiencies, like those with HIV or solid organ transplant patients on medications that make T cells less functionable to prevent rejection, have more severe disease,” says Dr. Ramirez. “It’s more than likely because they’re not really able to clear the virus effectively, and that gives the virus more time to replicate inside their body.”

However, you likely don’t need to be as concerned if you’re taking medication for an inflammatory condition like rheumatoid arthritis.

“Immunology is insanely complex, but it’s great that it’s so complex because our bodies have so much redundancy that having a deficiency in one area is usually able to be overcome,” says Dr. Ramirez. “For people who are immunocompromised, oftentimes there’s the opportunity for that to be overcome by other parts of the immune system — or in some cases, by medication being added or stopped.”

That’s one reason staying up to date with routine doctors’ visits and getting your underlying conditions to the best baseline possible during the COVID-19 pandemic is so important.

It’s also why you should be in touch with your doctor if you contract COVID-19 and take medications that affect your immune system.

Current guidance from organizations like the American College of Rheumatology generally advises that people on medications that affect the immune system should stay on them unless they are infected with COVID-19. Every person’s case will different, but your doctor may suggest temporarily stopping certain medications during COVID-19 infection to help your body fight it off more quickly.

Do I Need to Be Worried If I’m Taking Rituximab?

If you’re taking rituximab for a disease like rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, you likely don’t need to be overly concerned, but talk to your doctor if you have questions.

“There’s certainly more research that needs to be done for patients on rituximab, but many patients with conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus are on this drug,” says Dr. Sparks. “By and large, many of them have done well — meaning they haven’t been infected with COVID-19 or if they’ve gotten infected, they’ve gotten over it.”

While there isn’t currently firm evidence that this drug is dangerous in rheumatoid arthritis patients during COVID-19, the mechanism of the drug does have some theoretical risk for inadequate response to viral infection and lack of antibody production in general, he adds.

“More work needs to be done to understand what the actual risks are,” says Dr. Sparks. “Cancer patients typically receive higher doses and more frequent doses of rituximab and other B cell-depleting drugs than rheumatic disease patients.”

If I Am Immunocompromised, Should I Do Anything Differently Based on This Research?

If you’re doing everything you can to avoid contracting COVID-19 (wearing a face mask, social distancing, washing and sanitizing your hands, avoiding large groups of people, staying home as much as possible) and also keeping up with your regular doctor’s appointments, the best thing you can do is stay on your current course.

“Everyone should speak with their rheumatologist or health care provider if they feel like they’re particularly at risk, or to make sure their medication regimen is optimal,” says Dr. Sparks. “Patients with rheumatic diseases should certainly follow the general guidelines to social distance, wear a mask, and wash hands.”

There currently is no evidence to suggest that people with rheumatic diseases experience a longer course of illness with COVID-19.

“It seems like the disease course of our patients is pretty similar to the general population,” says Dr. Sparks. “That said, there is a caveat in that some of our patients are more likely to have inflammatory lung disease, so there could be a slightly higher risk of lung involvement from COVID-19. But by and large, their disease course, symptom onset, and the duration seems to be similar to that of the general population.”

If you’re working with your doctor to ensure your chronic disease is under control, you’ll have a better chance of recovering quickly if you were to contract COVID-19.

“If someone’s underlying medical conditions are as well-controlled as possible, they’re in a much better starting point if they do happen to get sick,” says Dr. Ramirez.

Get Free Coronavirus Support for Chronic Illness Patients

Join the Global Healthy Living Foundation’s free COVID-19 Support Program for chronic illness patients and their families. We will be providing updated information, community support, and other resources tailored specifically to your health and safety. Join now.

Avanzato VA, et al. Case Study: Prolonged Infectious SARS-CoV-2 Shedding from an Asymptomatic Immunocompromised Individual with Cancer. Cell. December 23, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.049.

Choi B, et al. Persistence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an Immunocompromised Host. The New England Journal of Medicine. December 3, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2031364.

COVID-19 vaccine: What’s RNA research got to do with it? University of Rochester. December 14, 2020. https://www.rochester.edu/newscenter/covid-19-rna-coronavirus-research-428952/.

DNA and RNA. Thomas Jefferson University Computational Medicine Center. January 9, 2020. https://cm.jefferson.edu/learn/dna-and-rna.

Interview with Jeffrey Sparks, MD, MMSc, Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston

Interview with Sydney Ramirez, MD, PhD, an infectious disease doctor and researcher at the University of California San Diego and La Jolla Institute for Immunology

Kemp SA, et al. Neutralising antibodies drive Spike mediated SARS-CoV-2 evasion. medRxiv. December 19, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.05.20241927.

Kupferschmidt K. U.K. variant puts spotlight on immunocompromised patients’ role in the COVID-19 pandemic. Science. December 23, 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/12/uk-variant-puts-spotlight-immunocompromised-patients-role-covid-19-pandemic.

People with Certain Medical Conditions. COVID-19. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html.

T cell. National Institutes of Health. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/t-cell.