Raise your hand if you’ve ever minimized or brushed off your arthritis or chronic pain symptoms … Yeah, we thought so.

When we asked members of the CreakyJoints Facebook community about this topic, Anne M. told us, “If I didn’t downplay my pain I wouldn’t talk about anything else! Boring!” Becka L. agrees. She says she downplays symptoms so “I don’t annoy people because everyone is like ‘you’re only 36’ and they get sick of the complaints. So I walk around and act normal if possible but my ankles, knees, and hips really hurt.”

The one place that you should never downplay your symptoms, though, is your doctor’s office.

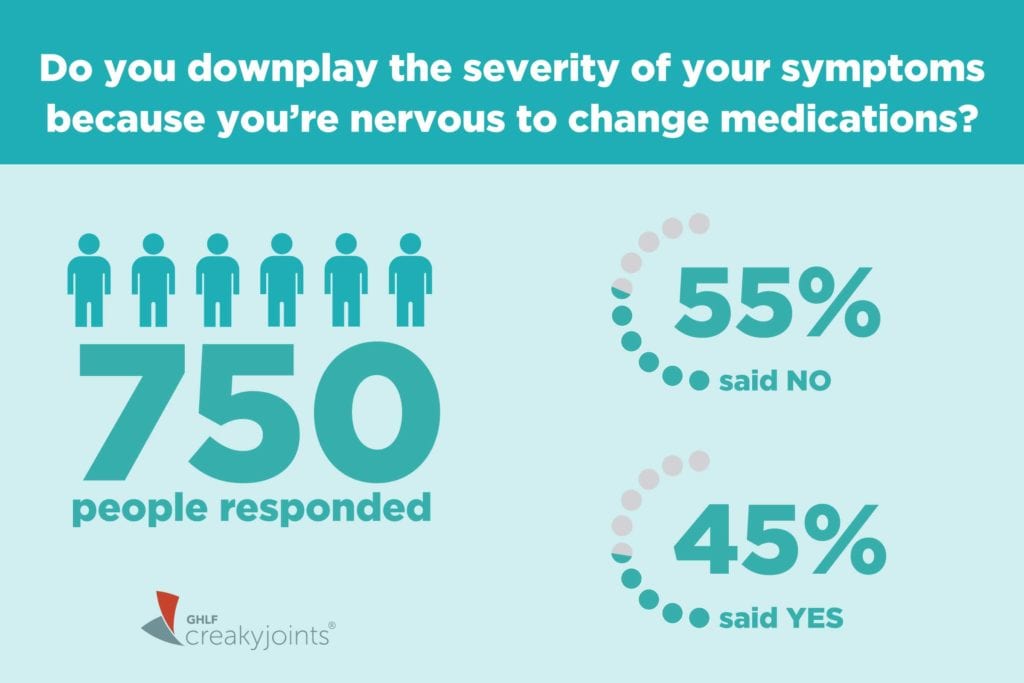

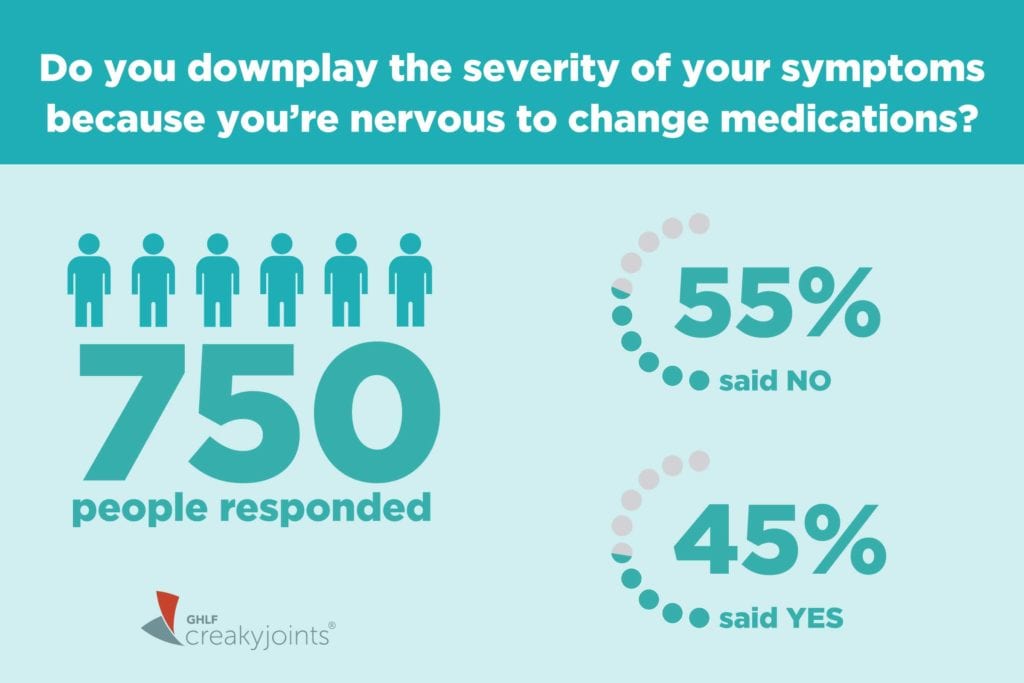

In our latest ArthritisPower Community Poll, we asked people: “Do you downplay the severity of your symptoms because you are nervous to change medications?”

While 55 percent of the 750 respondents said no, 45 percent said they did downplay their symptoms because they were nervous about a possible medication change.

Why Patients May Downplay Symptoms to Their Doctor

There are a few possible reasons patients don’t openly discuss a worsening of their symptoms with their doctor, according to Doug Roberts, MD, a rheumatologist in private practice in Sacramento, California and founder of PainSpot.com.

You think: “Things are ‘good enough.’”

Some patients may just accept — unnecessarily — that having pain or other symptoms is just part of having chronic disease like arthritis. They might compare how they feel now with how they felt when they were first diagnosed.

“I’m doing a heck of a lot better than I used to” is a sentiment Dr. Roberts will hear from his patients. “RA patients are a tough bunch,” he says. “They learn to tolerate symptoms.”

But remember, if you have inflammatory arthritis, your entire body — not just your joints — is affected. You might learn to tolerate stiff or swollen joints or make accommodations to make your daily life less painful, say, by using a golf cart instead of walking the course, or shortening your evening walks. But if your body is experiencing inflammation, you’re still at an increased risk of heart disease, certain cancers, and other inflammation-related diseases. (Read about the most common comorbid conditions with inflammatory arthritis, and what you can do about them.)

You think: “I don’t want to complain or impose.”

Some people may be reluctant to share with their doctor how they really feel because they don’t want to “feel like they’re whining, imposing, or overreacting,” says rheumatologist Ashira Blazer, MD, an instructor in the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health. Patients often have a hard time determining what’s serious or not, she says.

But your doctor would always rather you err on the side of caution and share how you’re feeling. It’s your doctor’s job to determine the significance of your symptoms; it’s your job to share them. Your doctor can’t help you if they don’t know what’s really going on.

“I don’t see it as complaining,” says Dr. Roberts. “The information you give me is just data that I use to help you. It gives me the best chance of helping you feel better.”

You think: “I don’t want to deal with the unknowns of a new treatment.”

It’s common for patients to worry about the what-ifs that come along with starting a new drug — whether potential side effects, new insurance hassles, or adjusting to a change in how a drug is administered. No doubt, change can be hard and scary. (Here’s more on how to read a health insurance formulary to see if your drug is covered.)

First, know that just because you’re experiencing new symptoms doesn’t automatically mean your doctor will want to change your drug. “More often than not, I don’t change medication when people report a new symptom or pain,” says Dr. Blazer. Your doctor will use a number of different inputs including your self-reported symptoms, bloodwork and imaging, a physical examination of your joints, and various health assessments, such as those that measure your quality of life, disease activity, and how functional you are — to discuss and decide with you whether a change in your treatment is warranted.

Second, try to ask your doctor to put any side effects you may be worried about in context. For example, “if your risk of getting an infection is 7 or 8 percent, that means that 92 or 93 percent of people won’t get an infection,” Dr. Roberts explains.

What’s more, “medications have side effects, but diseases have effects,” says Dr. Blazer. “No medication would be approved if it were more dangerous than having the disease itself. It’s important to have a healthy respect for the disease process — which can cause serious, lasting damage over time — and get things under control as quickly as we can.”

You think: “If I start a new medication, I’m going to have to take it the rest of my life.”

Concerns about how long patients will need to take a particular medication are among the most common rheumatologists hear. “Remember, it’s the nature of chronic illness to ebb and flow,” says Dr. Blazer. “Just because you need to escalate treatment now doesn’t mean you’ll need it forever.” Remissions do happen, she says. Once your symptoms are under control, you and your doctor may be able to discuss de-escalation.

The immune system is highly mysterious, and doctors are only beginning to understand why certain medications work for some people and not others, or why medications may become less effective for people over time. Your body can adapt to these immune-modifying drugs and learn how to produce antibodies that render them less effective. Changing up the drugs can help you recalibrate and achieve symptom relief.

With TNF inhibitors, for example, some drugs in that class attach to one part of the TNF molecule; others attach to a different part. Switching to a new drug may help your immune system in a way that’s slightly different — and, therefore, more effective for you. “Think of it as a different way of approaching the same problem,” says Dr. Roberts.

You think: “I’m scared of what these new symptoms could mean. I’d kind of rather not know.”

We tend to catastrophize the unknown, but more often than not, reality is less scary than what you might fear in your mind. When you have a new or worsening symptom, it’s natural to want to play ostrich—to stick your head in the sand and it hope it goes away. But you may be needlessly suffering, both physically and mentally.

“You might be thinking the worst, but your symptoms might be easily explained by your physician,” says Dr. Blazer. For example, she’s seen some patients delay bringing up very bad hip pain — “they endure weeks and weeks of pain on the side of their hip, and they don’t say anything until they’re convinced they need a hip replacement.” Turns out, they have something called trochanteric bursitis, which is inflammation of the bursa, a small fluid-filled sac near a joint. It’s very common, especially among side sleepers, and it has nothing to do with inflammatory, autoimmune arthritis. (It can be treated with rest, heat and ice, NSAIDs, and corticosteroids when the pain is severe.)

Or consider the story of RA patient Patty Deters. When pain and swelling flared in her hands again after having a lengthy period of remission, she was terrified. But it turned out that she had tendinitis from overuse injury — and her RA was still under control.

“A lot of times there is comfort in knowing whatever you have,” says Dr. Blazer. “There can be more suffering when you don’t know what’s wrong.”

The Truth About Making a Medication Change

Getting your disease under control, whether that means a medication change or not, is the best way to protect your body from lasting joint damage and serious comorbid diseases. And, let’s not forget the simplest benefit of all: “It’s good to feel better,” says Dr. Blazer. “No one wants to be miserable every day.”

In a recent study of 257 rheumatoid arthritis patients from the ArthritisPower research registry who were experiencing high disease activity, only 37 percent were offered a treatment change at their last physician visit. Some of that may be due to patients’ reluctance to share their symptoms and concerns with their doctors.

“It’s concerning that rheumatologists and patients may not be effectively engaging around treat-to-target goals even when symptoms, lab results, or patient-reported outcomes data reported via ArthritisPower warrant such discussion,” says W. Benjamin Nowell, PhD, director of Patient-Centered Research at the Global Healthy Living Foundation. “This study suggests that people living with RA need to feel empowered to discuss and consider treatment escalation with their doctor when both agree that a change is merited.” (Of those who were offered a treatment change, 72 percent agreed to the change; most intensified their treatment.)

There are more treatment options for arthritis than ever before, and more drugs are coming out all the time, says Dr. Blazer. “It doesn’t make sense to ignore symptoms, because there are always more options.”

Learn More About ArthritisPower

This question was one of our monthly ArthritisPower Community Questions, which offers ArthritisPower participants an opportunity to learn from each other and provide our research team insights.

If you’re diagnosed with RA or a musculoskeletal condition, you can participate in future polls like this, as well as research studies, by joining CreakyJoints’ patient research registry, ArthritisPower. As a patient-led, patient-centered initiative, our research team is committed to investigating research topics that matter most to you.