If you take biologic drugs to treat your chronic inflammatory autoimmune condition such as rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondyilitis, Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, or psoriasis, you’ve likely heard of biosimilars. And because understanding biosimilars can be complicated — medically and politically — you probably have some questions about them.

To be a more informed patient, download our new resource: A Patient’s Guide to Understanding Biosimilars. Medically reviewed by expert doctors as well as vetted by patients like you, it will give you a comprehensive, but understandable, overview of what’s happening with biosimilars so you can be a better advocate when speaking with your doctor, pharmacy, or insurance company.

The following questions and answers are developed from the information in our new guidelines.

What Are Biosimilars, Exactly?

To understand biosimilars you first need to understand biologic drugs. When you think of drugs you often think of chemical compounds like aspirin, a pill that you can pick up from your local pharmacy or supermarket. Biologic drugs are different. They are proteins made by living organisms, whereas traditional drugs are chemicals, referred to as small molecules. Biologic drugs are much larger in size than “small molecule drugs” like aspirin.

Biosimilars are not new drugs, but rather they are copies of biologic drugs that have been used to treat many diseases and conditions. Familiar biologic drugs include widely prescribed therapies like etanercept (Enbrel®), infliximab (Remicade®), adalimumab (Humira®), and others.

Each biosimilar is made using the same amino acid starting materials and the same precise, step-by-step processes as its reference drug — a well-tested, widely used biologic drug that’s already been on the market for years. All biosimilars are prescription drugs. You cannot get them without your health care professional’s prescription.

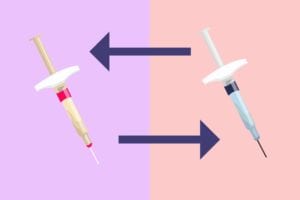

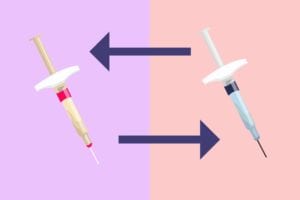

So Are Biosimilars Basically Generic Drugs?

You can think of biosimilars as sort of like generic drugs. But this is technically not true, since biosimilars are not completely identical copies of their reference drugs.

Each biologic and/or biosimilar drug is manufactured by a complex process that includes many precise steps. Even though the same exact process is followed every time that drug is made, because these are made by living cells, there may be slight changes from batch to batch. These variations are normal and acceptable, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Every lot meets the same high standards to be pure, safe, and effective.

Biosimilars use the exact same starting materials and similar manufacturing processes as the original biologic. They are designed and developed to be highly similar to the original drug upon which they are based, and they will not be approved as a biosimilar if they are not.

That’s why they’re called biosimilars: They’re made of biological materials (bio-) and are highly similar to an approved, widely tested, and prescribed biologic. A biosimilar is compared to its already approved reference product through an extensive array of analytical tests and clinical studies. Once it has been shown to be highly similar to the reference product, it is carefully reviewed and approved by the FDA before being released for use by patients.

How Are Biosimilars Named?

One thing that’s really important about a biosimilar is its label or name. When a biosimilar is developed, it’s given a name that tells you (and your doctor and pharmacist) what its reference drug is — the original biologic that it copies in a highly similar way — followed by a four-letter suffix, or tag at the end, that tells you which version of that drug you’re taking.

For example, there are three biosimilars of the biologic drug infliximab (Remicade®): Inflectra® (infliximab-dyyb), Renflexis® (infliximab-abda), and Avsola® (infliximab-axxq). Your doctor and pharmacist can use the suffix to identify which biosimilar you are using. By knowing the exact name of your medication, you can be clear when discussing your treatment plan with your provider, caregiver, and pharmacist. While they’re highly similar, and all must meet the same high standards to ensure that they’re safe and effective, your doctor may still prefer one over the other based on data from studies that are published about that exact biosimilar and the experience with other patients.

How Do I Know Biosimilars Are Just as Safe as Reference Biologics?

Yes, biosimilars are absolutely safe. Every drug that’s been approved for your use by the FDA must meet very high standards of safety. This includes all biosimilars and biologics. They are prescription drugs, so in the U.S., the FDA regulates how they are manufactured and delivered to you.

While biosimilars follow a shorter track to FDA approval, their makers still must test them thoroughly to show that they’re highly similar in structure and function to their reference products, that they’re safe, and that they work to treat diseases as they should.

One note: Biosimiliars are not required to be studied in all indications for which they will be approved for use. This is called extrapolation. If a biosimilar is approved for one indication of its brand name biologic — say rheumatoid arthritis — then all the indications of the brand name — psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, for example — are approved for the biosimilar.

In Europe, where biosimilars are more widely used, there are more than 700 million patient days of experience with biosimilars that illustrates their safety and efficacy in a real-world setting.

What’s the Deal with Switching from a Biologic to a Biosimilar — Is *That* Safe?

It is unlikely that switching between a biosimilar and its reference drug or among biosimilars of the same reference drug would result in clinically significant adverse effects. Keep in mind that any biologic drug — including biosimilars — typically varies slightly from lot to lot. The FDA requires that these variations fall within prespecified proven acceptable quality ranges and that they not result in any clinically meaningful differences.

It is normal to have concerns about receiving or switching to a new medication, including a biosimilar. The short answer to “Who should take a biosimilar?” is this: anyone for whom the biosimilar is indicated and who has not previously failed its reference product. Since biosimilars must demonstrate that they are safe and effective in order to be approved, patients can expect to experience the same effects with a biosimilar as they would with a reference drug.

Which Drugs Currently Have Biosimilars?

To date, the FDA has approved 30 biosimilars, the majority of which are indicated for cancer. Right now there are 15 biosimilars approved for use in the U.S. for patients with inflammatory diseases, but only six of these are available (there are three biosimilars for the reference drug Infliximab, or Remicade®, and three biosimilars for the reference drug Rituximab, or Rituxan®) in part because lawsuits among manufacturers are delaying the marketing of the others.

For example, the injectable biosimilars for adalimumab (Humira®) are approved by the FDA but, as the result of a lawsuit settlement agreement, won’t be available to patients in the U.S. until 2023.

For a complete list of currently approved biosimilars, download our patient guidelines for biosimilars.

Will Taking Biosimilars Save Me Money?

The short answer: maybe, but not yet. Here’s why:

Biologics are expensive to make. They’re expensive to buy. A single dose can cost $10,000 and up (and way up). Your insurance policy likely covers most of that cost, but there’s still a big impact on our overall health care costs because these very effective drugs are very expensive.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 was a U.S. law passed by Congress to set up a “fast-track” development and approval process for biosimilars. It was part of a larger set of laws called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was passed in 2010. Once the BPCIA became law, the FDA set up a step-by-step process for drug makers to follow to develop a biosimilar.

Because many analytical and human tests have shown that a certain biosimilar is highly similar to its reference product, safe, and equivalently effective for you, the FDA’s policy was that there was no need for a new biosimilar to duplicate clinical trials in patients with every disease. By doing so, development of a biosimilar could save time and money.

Biosimilars cost less than their reference biologic. However, patients in the U.S. have not seen direct dollar savings yet.

Manufacturers of biosimilars have given these drugs lower prices than their reference products. For example, infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra®) was introduced at a price that was 19 percent lower than infliximab’s (Remicade®) list price. In 2020, infliximab-axxq (Avsola®) was introduced at a list price which was 57 percent lower than infliximab’s (Remicade®) list price. However, those lower list prices have not resulted in lower out-of-pocket costs for you because insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers have not passed these savings on to you.

Health insurance companies say the lower price, while not passed on to patients, helps to keep the price of premiums low, but CreakyJoints has not seen evidence of this.

The RAND Corporation, a nonprofit that analyzes many programs and industries, published a report in 2017 that predicted that, overall, biosimilars would cut direct spending for biologics by $54 billion by 2026. The way the system is set up now, none of these savings go directly to patients. Lower costs for manufacturing, testing, and marketing biosimilars could translate into savings for the American health care system, which is good for Medicare and Medicaid because taxpayers pay for these programs.

As a patient, you deserve relief from rising drug costs. According to the lobbying group America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), as more biosimilars are approved and enter the market, competition will increase and prices should come down.

The FDA is looking into how the cost savings for biosimilars (or other drugs) are passed from their manufacturer to you, the consumer. There may be savings from corporate rebates or discounts that are not passed on to you. Hopefully, this will change so that you will pay less.

What Does the Future for Biosimilars Look Like?

There will likely be even more biosimilars coming onto the market in the next few years. Some that are already approved, but tied up in lawsuits, should become available to patients as well.

So if you’re using a biologic now, and you’re curious about whether a biosimilar may be a good option for you, here are some tips:

- Talk to your doctor. Find out if there is a biosimilar that is available, and if your doctor thinks it may be right for you.

- Find out if your insurance plan covers the biosimilar. If it doesn’t, ask them to notify you when coverage for a biosimilar becomes available.

- Ask your doctor and your pharmacist to explain how the biosimilar will work as part of your treatment plan. Ask any questions you have about its safety, effectiveness, and cost.

To stay on top of the issues around the availability and cost of biosimilars, join our patient advocacy group, the 50-State Network. This is a part of CreakyJoints that allows you to speak out to your community, your local, state, and federal elected officials, and many government agencies.

If you enjoyed reading this article, you’ll love what our video has to offer.