Key Takeaways:

- Confusion over increased risk of COVID-19 or its complications created anxiety and fear among rheumatic disease patients.

- Balancing the physical risk of getting COVID with mental toll of staying home proved stressful.

- Ethnic and racial health disparities during COVID-19 resulted in mistrust with health care system and lack of care.

- The pandemic may have amplified preexisting mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, and was linked with new concerns.

- Managing physical and mental health during times of stress is key for overall health.

There’s no question that the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic has (and continues to have) an emotional and social toll on everyone, and especially on people living with autoimmune or inflammatory rheumatic conditions. But what does this really mean in terms of patients’ everyday lives — and how does race, ethnicity, and culture impact people’s pandemic experiences and physical and mental health?

Researchers at University of Wisconsin-River Falls and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and a team of other research partners, including the Whelton Virshup CreakyJoints Arthritis Clinic and the Global Healthy Living Foundation, set out to better understand these unique experiences. They also wanted to learn about the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has on decision-making behavior and quality of life in underserved patient communities.

In a new study, presented during ACR Convergence 2021, the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, the research team conducted 60-minute interviews with 19 adults living with rheumatic disease between December 2020 and May 2021. The majority of participants had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). More than 50 percent of patients were from the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) community and more than 30 percent Hispanic/Latinx. Many were unemployed due to a disability (26.3 percent identified as disabled) and did not have health insurance (15.8 percent).

“We were doing interviews for about six months; the responses toward the end were pretty different than at the beginning when there was no vaccine,” says lead researcher Courtney Wells, PhD, MSW, MPH, LGSW, Assistant Professor and Field Coordinator at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls, who grew up with juvenile arthritis. “And even with the amount of time that we’ve been living with this, people still haven’t really had a chance to process all that has happened. They’re still trying to make sense of what is going on, and then new information keeps coming out.”

The Toll of COVID-19: What Patients Had to Say

The researchers learned that patients had a lot of questions about their risk for coronavirus infection and complications; going to the doctor and continuing treatments; visiting family and friends; and coping with preexisting or new mental health concerns.

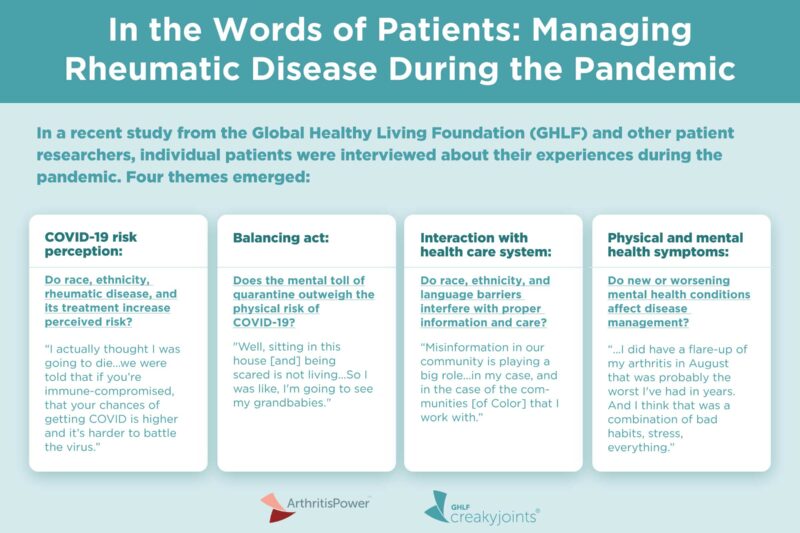

After analyzing the interviews, the researchers identified four themes that emerged about how participants were thinking about their experience during the pandemic and how it affected their behaviors and actions.

- COVID-19 risk perception: Confusion over whether having (and being treated for) a rheumatic disease increased risk for coronavirus infection and complications

- Balancing act: Whether, how, and when to engage in activities, social circles, and communities

- Interaction with health care system: Feeling unsupported by providers and public health authorities

- Physical and mental health symptoms: Self-reported increase in disease symptoms as well as new or worsening mental health conditions and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and trauma

COVID-19 Risk Perception

Especially at the beginning of the study, research was ongoing about whether or to what degree people with rheumatoid arthritis or other rheumatic conditions were at increased risk of COVID-19 or its complications — and this created confusion and paralyzing fear and anxiety for many patients.

Note: Research in this area is still ongoing, but current evidence suggests that rheumatic or inflammatory disease patients don’t have a greater risk of COVID-19 infection than the general population, though they may be more at risk of severe disease or complications. Factors such as age, comorbid conditions, and taking steroid medication are most associated with risks of severe disease, rather than having a rheumatic disease itself or taking other immunosuppressive medications.

Here’s what one study participant had to say:

- “I actually thought I was going to die from it if I had gotten it, because we were told that if you’re immune-compromised, that your chances of getting COVID is higher and it’s harder to battle the virus if you do have a pre-existing condition. Being fed all this information, it put me in a state where I felt that unstable feeling and being afraid of going out and making sure that I was doing everything I could to stay healthy. I was washing my hands every 20 minutes, and I was like, ‘I’m at home. Why am I doing this if I’m at home?’ It’s gotten to me in a mental way that way. That’s what it has done to me. That’s what I have felt whenever the thought of COVID and it affecting my personal health was… I thought of it to that extreme measure to where I thought I was going to die from COVID.”

Researchers also discovered that ethnicity and race played a big part in whether participants felt high-risk, and this caused additional stress for these communities.

“We had several people who identified as Asian American, and they talked about how the phrase ‘China Virus’ made them scared to leave their house. They had extra barriers that probably resulted in extra stress and maybe even worse health,” says Dr. Wells, noting that the study was qualitative and did not quantify these effects.

Balancing Act

Over the course of the study, researchers found that participants wrestled with how to balance the physical risk of getting COVID with the mental toll of not seeing friends and families. “It seemed that as time went on, people were so exhausted, and they were so burned out, that they leaned more toward the mental health piece,” says Dr. Wells.

Here is what study participants had to say:

- “Well, sitting in this house, being scared is not living. I mean, my days are passing me by and I’m not having a life. So I was like, I’m going to see my grandbabies.”

- “I can definitely see from the startup of COVID how strict we were [when deciding whether or not to do activities] versus now, it’s definitely on a scale. Little things started giving way and it was definitely more a mental health thing and less of ‘I’m learning more about COVID’…The type of person I am. I’m like, ‘Well, if there’s any risk, I don’t want to take it or you don’t need to be doing that. It’s unnecessary.’ But I got to a point where I can definitely tell you it was necessary for my mental health, for my partner’s mental health.”

Interaction with the Health Care System

Study participants from the BIPOC and Hispanic/Latinx communities expressed concerns about how their race and ethnicity could be affecting their health during the pandemic, including doubts about whether they were receiving high-quality care. They also addressed how misinformation and language barriers could be affecting others in their community, especially when it came to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and access.

“People who didn’t speak English were even more afraid because they didn’t have information in their language that they could understand available right away,” says study co-author Guadalupe Torres, a 23-year-old first generation Latina with rheumatoid arthritis. “And on top of that, being scared of what’s going to happen with the pandemic…added [another] layer.” Read more about Torres’ experience as a Latina patient-researcher during COVID-19.

Here is what study participants had to say:

- “I think the misinformation in our community is playing a big role…in my case, and in the case of the communities [of Color] that I work with. And language barriers, again, the lack of accessibility to information for those families. It has played a major role in these disparities, for example, …anyone [with or without documentation] can get a vaccine if they’re eligible for it, but our community doesn’t really know. I think there’s this lack of understanding from the authorities that people right now are just focused on surviving the day-to-day basis, like having enough food on their table at the end of the day and paying for rent, not being homeless.

- “My doctor said, ‘We’re really concerned about your health. It’s the worst it’s ever been. You need to be hospitalized, but you can’t come here.’ Because at that time, the hospital had totally converted to only COVID patients. They said, ‘We don’t even want you entering the county because it’s too dangerous for you here.”

- “And you never really know if it’s you or if it’s the color of your skin, but you’re so used to being looked at a certain way that you kinda know it’s the color of your skin and not anything about you.”

Physical and Mental Health Symptoms

Participants confirmed what researchers suspected and what other studies have shown: The pandemic led to an increase in rheumatic disease symptoms and mental health issues, which in turn, made caring for their condition that much harder.

The pandemic may have amplified and exacerbated preexisting mental health concerns, explains Dr. Wells. And some people in the study received a mental health diagnosis for the first time during the pandemic.

“We do need to value our mental health and take care of our mental health just as much as our physical health,” says Dr. Wells, adding that if you don’t feel well emotionally, or if you’re exhausted, burned out, or too anxious or fearful to leave the house, you’re not going to be motivated to care for your physical health.

Here is what study participants had to say:

- “There was the mental toll of quarantine. And then not being able to see my family. Then the chances of getting COVID. Then definitely being Asian, being Chinese, added just a little bit more to that. Because if I wasn’t, if I was white, that wouldn’t be a thing. I mean I wouldn’t be worried that someone would attribute the “China-virus” to me and that I might get attacked…It added to the stress and anxiety of an already stressful situation.”

- “We were on a prayer and a wing, nothing. When the shutdown came, we weren’t able to go to the doctor, see the doctor, or talk to the doctor…The shutdown really just took a toll on my body because I hadn’t any issues with my hands and my fingers in a long time. My fingers were swollen, they were locking up. I mean, when I did have a chance to go to [the doctor], I got two injections in one day, one in each hand.”

- “With COVID-19, I’ve definitely been a lot less active. And towards the beginning of it also a lot more stress-eating with everything going on. So it wasn’t a great combination. And I did have a flare-up of my arthritis in August that was probably the worst I’ve had in years. And I think that was a combination of bad habits, stress, everything. It lasted a couple of weeks. I could not get out of bed for a couple of weeks.”

Why These Findings Are Important for You

Everyone is dealing with their own unique set of pandemic-related challenges, including many that are directly related to having a chronic rheumatic health condition. But it’s helpful to identify common issues that emerge across patient communities in order to provide better resources and more targeted care.

Dr. Wells hopes that these patient perspectives allow rheumatologists and other health care providers to better understand what patients are really going through and, in turn, create an ongoing dialogue about mental health as well as health disparities. “We knew everybody was really stressed and overwhelmed,” says Dr. Wells, “but we didn’t know what went into that. And [now] we are able to see it in the rheumatology literature.”

Data like this could encourage providers to ask patients about their mental health, for instance.

The study findings are relevant beyond the pandemic, as they can help individuals better understand how to manage their physical and mental health during times of extreme stress, says Dr. Wells.

Found This Study Interesting? Get Involved

If you are diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, or another rheumatic or musculoskeletal condition, we encourage you to participate in future studies by joining CreakyJoints’ patient research registry, ArthritisPower. ArthritisPower is the first-ever patient-led, patient-centered research registry for joint, bone, and inflammatory skin conditions. Learn more and sign up here.

Wells C, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life of patients with rheumatic conditions: a qualitative analysis of perceived risk and decision-making [abstract]. Arthritis and Rheumatology. November 2021. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-the-quality-of-life-of-patients-with-rheumatic-conditions-a-qualitative-analysis-of-perceived-risk-and-decision-making.