Exercise is a mainstay part of managing arthritis. This is true whether you have osteoarthritis, a kind of wear-and-tear on your joints, or inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid or psoriatic, which occurs because your immune system is attacking your joints and causing systemic inflammation.

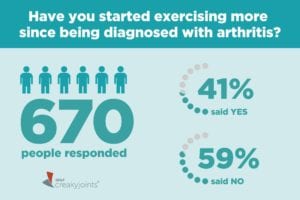

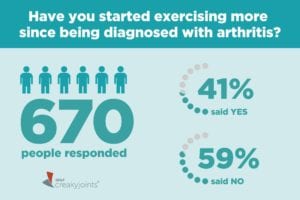

But a majority of arthritis patients said they have not increased the amount they exercise since being diagnosed, according to the results of our latest ArthritisPower Community Poll. We asked people if they’ve started exercising more after being diagnosed with arthritis; out of 640 respondents, 59 percent said no. Only 41 percent said yes.

Now, there are many reasons people with different kinds of arthritis may avoid exercising or increasing their physical activity levels, but it’s important to debunk and clarify a myth behind one of the big ones: the belief that exercise can exacerbate or worsen your disease.

“One of the biggest misconceptions about arthritis and exercise is people think, ‘Well, it’s not good for me,’” says exercise physiologist Lynn Millar, PT, PhD, FACSM, department chair of physical therapy at Winston-Salem State University. “I like to harp on the fact that exercise is one of the key treatments for arthritis. It will not make it worse. It will make it better.”

That’s not to say you should completely ignore your arthritis pain, stiffness, fatigue, and other symptoms and “power through” — having arthritis means you’ll have to think more carefully about the kinds of exercises you do, as well as the duration and intensity of your workouts.

But the most important thing is understanding that exercise, even if it’s very gentle and low-key, should be part of your arthritis treatment along with the medications you take to manage your disease.

The Science of Exercise Benefits for Arthritis

Research shows that exercise can help ease joint pain and stiffness, increase bone density and muscle strength, boost energy levels, improve mood and help combat depression and anxiety, promote better sleep, and reduce the risk of comorbid conditions like heart disease. And different kinds of exercise offer different degrees of these benefits. These are the four main types of exercise that the American College of Rheumatology recommends including in a regular fitness routine:

1. Flexibility exercises include range-of-motion (ROM) and stretching exercises. These help to maintain or improve the flexibility in affected joints and surrounding muscles. This contributes to better posture, reduced risk of injuries, and improved function. “A range of motion exercise means aiming to get the normal amount of movement you should have within a joint,” says Chris Gagliardi, an American Council of Exercise (ACE) certified personal trainer and ACE Resource Center manager. Think circling your ankles in clockwise and counterclockwise circles or bending and straightening your knee while sitting in a chair.

2. Strengthening exercises work muscles a bit harder, which provide greater joint support. Strong muscles also help reduce bone loss related to inactivity, some forms of inflammatory arthritis, and the use of certain medications, such as corticosteroids. This can include using free weights, a weight machine, or elastic bands. “As we lose muscle strength that means, biomechanically, there’s more stress going to the joint,” says Millar. “Muscles help absorb force and stress. If you lose muscle strength, then that force and stress is not being spread out and more of it goes to the joint.”

3. Aerobic exercises use the large muscles of the body in a repetitive and rhythmic manner (think walking, cycling, or swimming). This improves heart, lung, and muscle function. Aerobic exercise is especially important in helping you maintain a healthy weight and reducing your risk of heart disease.

4. Body awareness exercises include activities to improve posture, balance, joint position sense (proprioception), coordination, and relaxation. Yoga and tai chi are good examples.

Not exercising when you have arthritis can create a vicious cycle, explains Millar, who herself has osteoarthritis in her left knee and foot, both hands, and her right elbow. “Yes, it hurts, but the more you rest, the more out of condition you get, and then the more it hurts,” she says. “Not moving your joints can make the progression of arthritis worse.”

When Exercise Is a Problem

Many people with arthritis know exercise is good for them — and they want to be more physically active than they’re able to be. Tien Sydnor-Campbell, 48, knows this firsthand.

In high school she was a competitive swimmer and rode her bike 22 miles round-trip to work; she kept up with biking and swimming recreationally throughout her adulthood. In fact, Sydnor-Campbell was training for a triathlon in her late thirties when she first noticed a series of strange and seemingly unrelated symptoms — jaw pain, pain that caused her knees to lock, flares of pain in her wrists — that ultimately led to her being diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at age 40.

Sydnor-Campbell still tried to go to the gym right after she was diagnosed, but her pain levels were high. Those early days at the gym did not go well. She struggled with one activity after another — couldn’t use the usual weight machines she did for arm exercises, even when she dropped the amount of weight from 20 pounds down to five. Same issue when she tried a machine to work the quadricep muscles in her legs. The last straw was when she found herself struggling to even wriggle into her bathing suit, let alone swim her usual laps in the pool. She felt too weak to lift her arms over her head.

“This cannot be happening. You’re going to take swimming away from me, really?” she recalls thinking. “Being physically unable do something I really want to do was a position I’d never found myself in my entire life. I still mourn my athletic ability.”

In the eight years Sydnor-Campbell has been living with RA, her relationship with exercise has changed dramatically. She’s had to scale way back and adjust to a new reality. Sometimes a short walk around her block, or an outing to food shop at the local grocery store, is about all her body can physically handle, and that’s OK. “Any chance I can now, when I feel like I can walk, I walk. If I don’t feel like I can walk much, I don’t. My body keeps reminding me that I’m not who I was, while in my head I still am.”

A Few Smart Exercise Rules for Arthritis

Sydnor-Campbell is following one of the cardinal rules of exercising with arthritis: don’t overdo it when you’re having a flare. According to the American Council on Exercise, “individuals with rheumatoid arthritis should not exercise during periods of inflammation, and regular rest periods should be stressed during exercise sessions. However, gentle [range-of-motion] exercises are appropriate during these conditions.”

Here are more basic rules to keep in mind:

Time your exercise around when you feel your best.

If you have a lot of stiffness in the morning, for example, you might not be able to go to the gym or do an exercise video, but you could do low-impact range-of-motion (ROM) stretches, even while you’re seated on your bed. If you’re prone to fatigue, doing a few short bursts of activity (think: 10-minute walks) could help break up the day and provide a much-needed energy boost. If you have difficulty sleeping at night, avoid exercising too close to bedtime.

Wear good athletic shoes with shock absorption and support for your feet.

“If you’ve got poor shoes, that’s transmitting more force through your joints,” says Millar. If you can’t remember the last time you got new workout sneakers, it’s time for a new pair.

Ask for help.

If your arthritis symptoms don’t feel well controlled, it’s a good idea to see a physical therapist or exercise physiologist with experience treating people with arthritis. Even if you’re used to exercising, it’s a good idea to ask a trainer to double-check your form and make sure you’re not doing any strength training exercises incorrectly. “If you continue to do a movement with improper form, it could have more wear-and-tear on your body than if you had proper alignment,” says Gagliardi.

Anything is better than nothing.

Sometimes exercise can feel like an all-or-nothing mentality: If I can’t do an hour at the gym, why bother at all? That kind of thinking is particularly toxic for people with arthritis, because more often than not, a long or intense workout session isn’t appropriate. “Really, any amount of activity you get beyond resting offers improvements,” says Galardi. “Maybe you can only tolerate five minutes at a time and then need to stop or rest. Doing that a few times throughout the day can add up.”

Know the difference between discomfort and pain.

It’s normal to be uncomfortable after exercising, especially if your body isn’t used to it, but you shouldn’t feel like you’re in pain. “If pain is greater two hours after exercise than it was before, reduce the length and intensity of your next session,” advises the American College of Sports Medicine.

Millar had to stop jogging for more than a month when arthritis flared up in her knee. That first week, she could walk only every other day. “I’m never going to be down to a zero pain with my knees when I go out to exercise,” she says. “But I don’t want it to start feeling worse. I have to be listening to my body and paying attention. Part of it is knowing and telling yourself, ‘You can’t just sit still.’ Back off a little, but don’t stop completely.”

Sydnor-Campbell has found a mantra that’s helped her cope with her new normal: Be gentle with yourself. “Don’t get frustrated. You know what this is. You know what you have. It might not always be like this, and there is hope,” she says. “I keep telling myself this over and over.”

Keep Reading

- The New 2018 Exercise Guidelines in 4 Words: “Move More, Sit Less”

- 12 Healthy Habits for Inflammatory Arthritis Worth Adding to Your Daily Routine

- 8 Daily Arthritis Hand Exercises that Can Soothe Your Pain