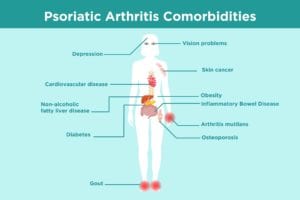

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of inflammatory arthritis known for affecting the skin (causing psoriasis) and the joints (causing arthritis pain and swelling). In psoriatic arthritis, your body’s immune system mistakenly sets off uncontrolled inflammation and attacks your own tissues. The immune system typically uses inflammation to fight disease or heal an injury. It doesn’t shut off, though, when you have psoriatic arthritis. Instead, the inflammation attacks healthy skin, nails, and joint tissues, causing pain and damage.

Main psoriatic arthritis symptoms include psoriasis plaques on the skin; joint pain and stiffness; swollen fingers and toes; foot pain; and lower back pain. Psoriatic arthritis can present very differently from person to person. Some patients have more skin involvement; others more joint involvement. Regardless, psoriatic arthritis is a “systemic” disease, which means it can affect your entire body and increase your risk for seemingly unrelated diseases like heart disease, diabetes, depression, and more.

In addition to clearing the skin, easing joint pain, and preventing future joint damage, a mainstay of psoriatic arthritis treatment is trying to prevent these systemic complications.

Once you read through this list of psoriatic arthritis complications, you should bring up any questions or concerns you have with your doctor. You may need to create a health care team of different specialists — such as a cardiologist along with your rheumatologist or dermatologist — or facilitate better communication between them to ensure you’re getting optimal care for your psoriatic arthritis and its comorbidities.

Common Psoriatic Arthritis Comorbidities

Psoriatic Arthritis and Cardiovascular Disease

For reasons scientists are still studying, there is a strong connection between heart disease risk and psoriatic arthritis. For example, a 2016 study in the journal Arthritis Care & Research determined that people with PsA were 43 percent more likely than average to develop cardiovascular disease. People with psoriatic arthritis also had a 22 percent greater risk of cerebrovascular disease, which can cause stroke.

Psoriatic arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis can impact your entire body, including your cardiovascular system. Blood vessels harden and become damaged, known as atherosclerosis, which increases the risk for heart attacks and strokes. Other PsA comorbidities, including diabetes and obesity, further raise the risk of cardiovascular issues.

When it comes to psoriatic arthritis comorbidities, “the main conversation we have [with patients] is about cardiovascular risk,” says Samar Gupta, MD, associate professor at the Michigan Medicine Rheumatology Clinic at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He specializes in psoriatic arthritis and rheumatology. “We see cardiovascular disease the most in people who aren’t treated.”

Know the warning signs of a heart attack. Signs include shortness of breath, pain in the upper body, extreme fatigue, and discomfort or pain in the chest. Warning signs of a stroke include difficult speaking, slackness on one side of the face, and arm weakness (usually on one side).

You can reduce your risk of heart disease and stroke by focusing on risk factors you can control. Talk to your doctor about your blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar, and what kind of heart disease screening tests you should get.

Look at healthy lifestyle changes you can make, such as eating a healthier, anti-inflammatory diet, getting regular exercise, and quitting smoking. In psoriatic arthritis in particular, losing weight is an important PsA management tool.

“For people who are very overweight, the [PsA] drugs don’t work as well,” says Kevin McKown, MD, a rheumatologist at University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, Wisconsin. “You can help reduce your cardiovascular risks with the right diet and weight loss.”

As for PsA treatment and how it impacts heart disease risk, doctors still don’t know a lot. It stands to reason that treating inflammation in psoriatic arthritis would help to lower heart disease risk, but more research is needed in order to prove this is the case. You should also be cautious about taking medications that may increase heart disease risk, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Psoriatic Arthritis and Obesity

Obesity is a known risk factor for developing psoriatic arthritis. A study published in the Archives of Dermatology found that being obese before age 18 increases the risk of psoriatic arthritis and leads to the earlier onset of disease symptoms.

Obesity also impacts the management of psoriatic arthritis. A study in the Annals of Rheumatic Disease found that obese people with psoriatic arthritis were 48 percent less likely than their normal-weight counterparts to have minimal disease activity (measured by pain, tender joints, and other factors) after a year. Excess weight can interfere with the effectiveness of drugs that are often used to treat psoriatic arthritis. Adalimumab (Humira), for example, is given at a single, fixed dose, regardless of a patient’s weight. A study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology found that obese people with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis don’t get as much relief from symptoms when using anti-TNF biologic drugs like adalimumab (Humira) compared to patients at a healthy weight.

Exactly how excess weight affects psoriatic arthritis and vice versa is still being studied. Researchers know that fat tissue releases inflammation-causing proteins (cytokines), which are also involved in the inflammation process in psoriatic arthritis. What’s more, when you carry around extra weight, you weigh down joints. Losing weight or maintaining a healthy weight can take pressure off your knees and back.

Once you lose weight, you’re likely to have more success with medications like conventional disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologics. Weight loss can improve your overall health and even increase your chance of going into psoriatic arthritis remission. Dr. Gupta says that each pound of weight loss can reduce the load on your knees by four pounds.

If you’re currently overweight, following a Mediterranean-style diet (fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and fish) may help you slim down and, in turn, possibly improve your psoriatic arthritis symptoms. Regular exercise can help maintain your weight and control your psoriatic arthritis. Read more about how to follow a healthy psoriatic arthritis diet.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Diabetes

People with psoriatic arthritis are known to have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which is a metabolic disease that happens when you can’t use the hormone insulin properly and your blood sugar levels become elevated. A review of studies in JAMA Dermatology found that psoriatic arthritis increases the risk of type 2 diabetes by 53 percent.

“It’s not entirely clear why the two conditions are often found in the same people,” says Daniel Solomon, MD, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine, at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. “It may be that the systemic inflammation of psoriatic arthritis also causes diabetes. However, it’s more likely that some of the risk factors for both diabetes and psoriatic arthritis are shared, such as genetics, obesity, and other metabolic factors.”

Talk to your rheumatologist or primary care provider if you have increased thirst, hunger, blurred vision, or fatigue, which are symptoms of type 2 diabetes.

Your primary care doctor should be monitoring your blood sugar to make sure you don’t have diabetes or prediabetes. Your doctor may check your fasting blood sugar at regular visits or do a blood test called A1C, which looks at your average blood sugar levels over the past three months. The higher your A1C level, the poorer your blood sugar control and the higher your risk of diabetes complications.

Two of the best ways to prevent type 2 diabetes if you’re at an increased risk due to psoriatic arthritis is to get regular physical activity and lose weight if you need to do so. Cardiovascular exercises and strength training help move sugar out of your bloodstream. Losing weight can help improve psoriatic arthritis symptoms, prevent diabetes in the first place, or help you achieve better control of your diabetes if you’re already diagnosed.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Gout

A different kind of inflammation-driven arthritis, gout is caused by the buildup of uric acid (a normal waste product in your body) in the blood. When uric acid levels are elevated in the blood, they can accumulate in a joint and cause an inflammatory response. That often triggers severe pain and swelling.

Psoriatic arthritis and gout are connected because uric acid is thought to be a product of rapid skin cell turnover and inflammation that occurs in PsA. A study published in the journal Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases found a connection between high uric acid levels and psoriasis, and suggested a strong connection with psoriatic arthritis. For men and women with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, the risk of developing gout was nearly five times more than study participants without psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.

“The link is thought to be related to skin inflammation and release of uric acid from high turnover of skin cells,” says Dr. Solomon. Obesity also plays a role, since it’s a risk factor for both gout and psoriatic arthritis, says Dr. McKown.

Proper treatment of gout is crucial to prevent long-term joint damage and serious gout comorbidities. Lowering uric acid levels with medication can prevent gout flares and the long-term complications that go with them. Medications called xanthine oxidase inhibitors limit the amount of uric acid your body produces. These include allopurinol (Zyloprim and Aloprim) and febuxostat (Uloric). Another class of drugs called uricosurics help your kidneys remove uric acid from the body. These include probenecid (Probalan) and lesinurad (Zurampic). An infused drug called pegloticase (Krystexxa) can help the body eliminate uric acid in people whose gout hasn’t been controlled with other medication.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis, which causes bones to become thin, weak, and prone to fractures, and psoriatic arthritis are closely linked. A study in the Journal of Dermatology found a high prevalence of osteopenia, an early form of osteoporosis, in people with psoriatic disease. When researchers looked for signs of osteoporosis and osteopenia in 43 psoriatic arthritis patients, 60 percent of patients had osteopenia and 18 percent had osteoporosis.

Several possible explanations are behind the link between psoriatic arthritis and osteoporosis. One is inflammation caused by psoriatic disease. Several inflammatory proteins (cytokines) involved in psoriatic disease are also involved in osteoporosis. Corticosteroid medications used to control inflammation in PsA have bone thinning as a known side effect. Also, joint pain and stiffness in psoriatic arthritis may lead to physical inactivity, which can cause bones to weaken.

You may be at risk for osteoporosis and not know it. Because osteoporosis is often asymptomatic (it rarely causes symptoms until a fracture occurs), talk to your health care provider about how often to get bone density scans, which can help determine if you have osteoporosis before you experience a fracture. Some health care providers may recommend that people with psoriatic arthritis or who have other known risk factors for osteoporosis get bone density scans earlier or more frequently than what is recommended for the general population.

Prevent bone loss by doing weight-bearing exercises as well as taking calcium, vitamin D, or osteoporosis medications (if your doctor recommends them) to slow bone loss or help rebuild bone.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Depression

Mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety are common in people with arthritis in general, but those with psoriatic arthritis may have a particularly high risk. Research presented at the 2018 meeting of the American College of Rheumatology found that patients with PsA were more likely to report higher levels of depression than those with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). A study published in the Journal of Rheumatology found that people with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis were found to experience higher rates of anxiety and depression than those with psoriasis alone.

Psoriatic arthritis can seriously impact patients’ quality of life. Psoriasis skin plaques can affect your appearance and self-esteem. Chronic pain, fatigue, and reduced mobility can make socializing difficult and increase loneliness and isolation. All of this can cause emotional distress and contribute to depression.

Inflammation itself may play a role in the connection between psoriatic arthritis and depression. The same processes that trigger inflammation in psoriatic disease may create brain changes that impact your emotional state. For example, research in the journal Nature Reviews Immunology found that raised levels of inflammatory cytokines may also contribute to depression. The cytokines may reduce the availability of chemical messengers including serotonin (which regulates mood), dopamine (which plays a role in pleasure), and norepinephrine (which regulates emotions). Low levels of any of these chemical messengers can contribute to depression.

Symptoms of depression include loss of interest in activities you once enjoyed; persistent helplessness, hopelessness, or sadness; sleep pattern changes; difficulty concentrating; and withdrawing from your circle of friends.

If you have depression, it’s important to explore the ways you can treat it, including taking antidepressant medication. Not treating your depression can also affect your ability to manage your psoriatic arthritis, creating a vicious cycle of feeling unwell.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory diseases of the gut tend to co-occur in psoriatic arthritis. With inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the body mistakes healthy tissue for a foreign invader and attacks it. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis affect the walls and tissues of the intestines.

A review of studies in the journal JAMA Dermatology found that of the nearly 6 million people included in the review, psoriatic arthritis was linked to a 1.7-fold increased risk of ulcerative colitis and a 2.5-fold increased risk of Crohn’s disease. It may the case that people with IBD and psoriatic arthritis have similar genetic mutations that lead to the onset of both diseases. One possible explanation is that there is a change in gut bacteria that leads to inflammation that affects both the GI tract and the joints in the spine and elsewhere in the body.

Symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease include blood in your stool, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and cramping. Symptoms can be mild to severe and come and go with periods of flares.

The same biologic medications, such as TNF inhibitors, can be used to treat both psoriatic arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. If you have inflammatory bowel disease, a gastroenterologist can work with you and your rheumatologist on a treatment plan. In addition to medication, they may suggest tweaks to your diet, such as limiting dairy; eating low-fat foods (avoid butter, creamy sauces, and fried foods); and restricting high-fiber foods, depending on your condition.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Skin Cancer

There appears to be an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer, compared with other kinds of cancer, among psoriatic arthritis patients, according to a study on more than 43,000 patients with psoriatic arthritis published in the journal Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism. More research is needed to understand whether the disease itself is responsible for the risk increase, or whether medications used to treat PsA are affecting cancer risk.

In that study, for example, researchers found that biologic drugs used to treat PsA did not seem to affect cancer risk, but conventional disease-modifying drugs, such as methotrexate, did appear to have an increased relative risk. But the finding is far from conclusive. The researchers acknowledged that the studies that found this result had small numbers of patients and didn’t have adequate controls, “leaving it open to interpretation whether cancer risk is associated with the therapeutic agent or with the disease itself. No clear conclusion can be drawn regarding whether conventional DMARD use may increase cancer risk.”

That said, it’s better to be safe than sorry when it comes to skin cancer screening. Patients with psoriatic arthritis should be aware of the potential for an increased risk of skin cancer and see a dermatologist annually for a regular skin check. This allows your doctor to monitor and remove any troublesome moles at the earliest possible stage.

Skin cancer symptoms include a scaly, sore, or peeling spot that won’t go away or keeps recurring in the same spot, says Caren Campbell, MD, a dermatologist who practices in San Francisco. Also look for a new bump that bleeds, hurts, or doesn’t resolve; a changing or new mole with irregular borders or multiple colors; or a mole that doesn’t look like your others.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) occurs when fat accumulates in liver cells and the deposits aren’t the result of alcohol abuse. Having any inflammatory arthritis appears to increase your chances of developing NAFLD, but psoriatic arthritis has the strongest link.

No one knows exactly why, there are a few possible explanations. Other metabolic diseases including type 2 diabetes and obesity are common in both PsA and NAFLD. Underlying inflammation may be a factor, as can taking arthritis medications that affect the liver, such as methotrexate. For example, a 2017 study in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology found that people with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis were at increased risk for liver disease, including NAFLD, whether or not they were taking systemic therapy, such as methotrexate. The risk was even higher for those who were.

Fatty liver disease has few symptoms during the early stages; when symptoms such as an enlarged liver, abdominal pain, or jaundice show up, that means the disease has already become advanced. This is why it’s important for doctors to regularly monitor your liver function (through blood tests) to watch for signs of liver damage. Weight loss and exercise are two of the best ways to prevent or reverse non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Being at risk of NAFLD may also affect which medications your doctor prescribes to ensure it doesn’t have any negative impact on the liver.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Vision Problems

The eye disease uveitis, or inflammation of the uvea, the middle layer of your eye, is common among people with psoriatic arthritis.

Uveitis symptoms include redness, eye swelling, eye pain, watery eyes, blurred and impaired vision, and sensitivity to light. It’s usually present in only one eye at a time. It typically comes on suddenly and becomes severe quickly. The condition can lead to cataracts, glaucoma, or even vision loss if left untreated. Uveitis happens in PsA because systemic inflammation can affect the eye, says Dr. Solomon. “The family of arthritis spondyloarthritis — which includes ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis — all have increased risk of uveitis,” says Dr. McKown. “It’s not really understood why but it’s a hallmark of these diseases that people get.”

Steroid eye drops often are an effective treatment to help lower the inflammation in your eye. If the drops don’t work, you may be given corticosteroid pills or steroid eye injections. While uveitis is being treated, you can also wear dark glasses so that bright lights don’t bother you.

Recurrent bouts of uveitis may mean you need a PsA treatment change, such as escalating to a biologic drug.

When you have PsA, it’s important to visit an ophthalmologist at least annually to get your eyes checked. See an eye doctor promptly if you develop any unusual vision changes or eye symptoms.

Psoriatic Arthritis and Arthritis Mutilans

Arthritis mutilans is a severe, destructive form of arthritis that is most commonly seen in people with psoriatic arthritis. The rare condition damages and destroys joints and bones. Normally, bones can break down and rebuild. But when you have arthritis mutilans, the bones can’t rebuild. Instead, the soft tissues of the bones collapse. Arthritis mutilans can impact the fingers, hands, wrists, and feet.

Thanks to effective treatment for psoriatic arthritis, arthritis mutilans is rare today, says Dr. Gupta. It’s most likely to develop in people with psoriatic arthritis who haven’t received any treatment.

If you do develop arthritis mutilans, early treatment can help prevent further bone loss. While bone tissue can’t be restored fully, treating arthritis mutilans can help slow bone destruction.

Arthritis mutilans treatment most often includes DMARDs such as methotrexate, a TNF inhibitor, or both. A paper published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology described three patients with psoriatic arthritis mutilans who were followed up for two years. They were treated with etanercept (Enbrel), a TNF-alpha targeting agent that is used to treat psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. The patients had significant joint and skin improvement with this therapy, though they still had lasting deformities from years of this progressive disease.