If you’re from a certain area, you know at least a little about Lyme disease. It’s the reason your parents made you cover up any time you’d be remotely close to a wooded area and checked you religiously for ticks upon your return home.

Lyme disease is an infectious disease spread by certain ticks in certain parts of the United States and Europe. Early on, it can cause flu-like symptoms and a telltale bull’s-eye rash. But if Lyme disease isn’t caught and treated with antibiotics promptly, the infection can eventually spread through the body. The most common late-stage symptoms include joint swelling and pain, a condition known as Lyme arthritis.

Historically, about 60 percent of people with undiagnosed, untreated Lyme disease would develop Lyme arthritis, according to a study in the journal Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Lyme arthritis, however, shouldn’t be confused with chronic Lyme. As its name implies, chronic Lyme is a condition that doesn’t go away with one course of antibiotics. It’s controversial in the medical world, partly because some patients are diagnosed with chronic Lyme when lab tests don’t show evidence of an infection. Some doctors insist that chronic Lyme patients’ symptoms fade when they stay on antibiotics; others argue that it’s a different disease entirely and that long-term antibiotics will only create more side effects.

Late-stage Lyme, on the other hand, is curable Lyme disease that’s progressed and lead to complications such as arthritis.

Lyme Arthritis Causes

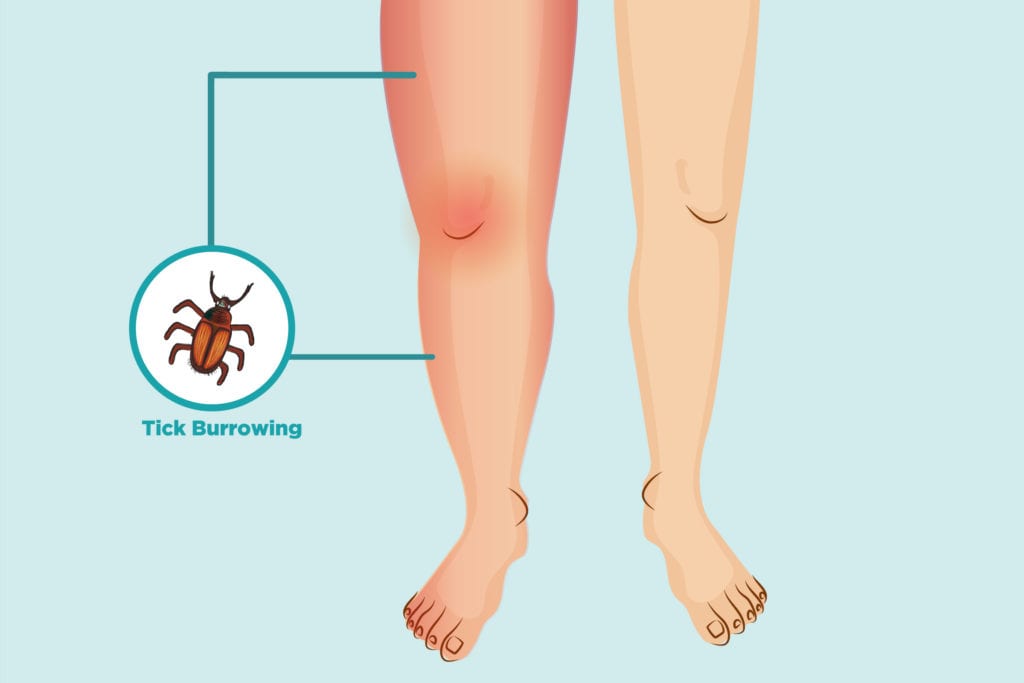

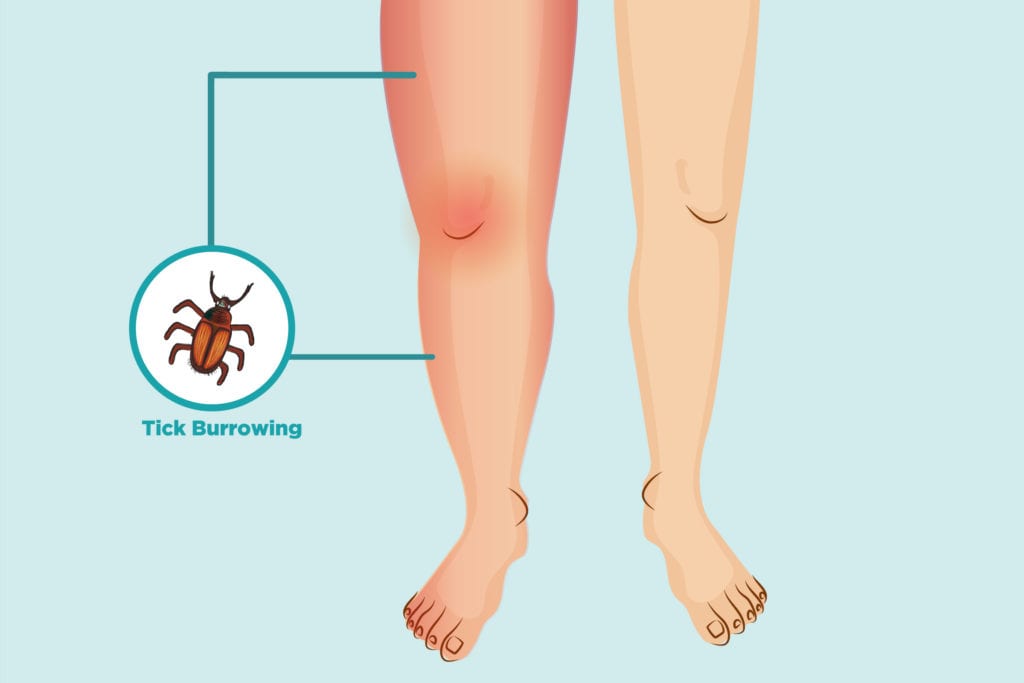

Lyme arthritis is caused by Lyme disease. Lyme disease occurs when deer ticks in parts of North America and Europe that carry Borrelia burgdorferibacteria infect humans. Once the bacteria have invaded, they can spread around and infect other parts of the body — including the joints.

When that happens, the joints (particularly large ones like the knee) become swollen and painful. Typically, by the time the late-stage symptoms like Lyme arthritis show up, the early-stage signs of Lyme disease (like fever and rash) have gone away.

Lyme Arthritis Symptoms

By the time late-stage Lyme disease has developed into arthritis symptoms, the pain feels different from those early flu-like symptoms.

“The early stages of Lyme disease are more consistent with a viral infection where you just kind of hurt all over. Maybe some achiness in the joints and general discomfort, but it’s more generalized and there’s not associated swelling,” Laura Lewandowski, MD, clinical fellow with the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases’ Systemic Autoimmunity Branch.

Here are some traits that distinguish late-stage Lyme arthritis from other types of arthritis:

1. Lyme arthritis is not symmetric on both sides. This is unlike many types of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

2. Lyme arthritis usually causes pain in only a few joints. It usually causes pain in fewer than five joints at a time — sometimes even in just one joint. Lyme arthritis most often affects the knees and ankle, but it can affect other joints too.

3. Lyme arthritis pain isn’t constant. It also usually isn’t enough to keep a person from walking, says Dr. Lewandowski.

4. Lyme arthritis pain could look more painful than it feels. “People can get a very swollen knee, but that, paradoxically, is not very painful,” says Shing Law, BM, BCh, board-certified academic rheumatologist and clinical research fellow in rheumatology at the University of Oxford.

However, the symptoms of Lyme arthritis can mimic other types of arthritis, which can make it tricky to diagnose, especially if the patient never found a tick or has reason to suspect they have Lyme disease.

Lyme Disease vs. Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Lyme arthritis is most common in 7- to 10-year-olds, so it tends to be confused with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), a type of inflammatory arthritis that affects young children, says Dr. Lewandowski. If a child lives outside the areas where Lyme is common — New England, the Mid-Atlantic, Wisconsin, and Minnesota — it’s more than likely JIA, not a tick-borne disease.

To answer the JIA vs. Lyme arthritis question, doctors can test patients for signs of Lyme disease. The first step is to test for antibodies with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test. If that comes back positive, a doctor will likely order something called a Western blot test, which will show certain darkened bands if there are antibodies fighting a Borrelia burgdorferi infection.

Lyme False Negatives and False Positives

The tests have been criticized by some for showing false negatives (when a test says you don’t have Lyme disease when you actually do) during the early stages of Lyme. But “at the point where Lyme arthritis comes along, those tests should definitely be positive,” says Dr. Lewandowski.

False positive Lyme test results can also throw a wrench into a Lyme arthritis diagnosis. This is when the test says you have Lyme disease but you actually don’t.

In patients who have infectious mononucleosis (mono) or test positive for an antibody called rheumatoid factor (RF), those other conditions could cross-react with the Western blot test and make it look like you have Lyme when it’s actually something else, according to a study in Pediatric Rheumatology. RF is associated with rheumatoid arthritis, so there’s a chance that rheumatoid arthritis could be the real root of the joint pain.

However, rheumatoid arthritis tends to be symmetric, but Lyme arthritis rarely is, which could be a sign that it isn’t Lyme after all.

If antibiotics for Lyme treatment don’t seem to be working, a doctor can test fluids from the knee for signs of Lyme, says Dr. Law. A negative test would indicate the Lyme has cleared out and something else is causing the pain.

In rare instances, the initial Lyme infection can trigger a separate autoimmune condition, adds Dr. Lewandowski. In that case, the antibiotics should be dropped in favor of a new treatment plan such as anti-inflammatory drugs.

Lyme Arthritis Treatment

Compared to chronic Lyme — a controversial condition that doctors debate whether antibiotics help — Lyme arthritis treatment plans are more straightforward. For late-stage Lyme, doctors will prescribe a 28-day course of an antibiotic such as doxycycline or amoxicillin. It’s a longer course than would be prescribed if the Lyme were caught early, but the extra time should be enough to get rid of all Lyme disease symptoms, including joint pain.

If there was still joint swelling after those four weeks, another 28-day treatment would be prescribed, possibly through IV. The joint pain from Lyme arthritis will subside as the infection clears, though patients can use OTC meds like ibuprofen to ease the pain in the meantime, says Dr. Lewandowski. In the rare cases where the joint pain does persist after two months of antibiotics, there’s evidence that disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or surgery could resolve the arthritis for good.

A symptom of late-stage Lyme disease, Lyme arthritis shouldn’t linger after proper treatment. If symptoms persist, find a doctor who will work with you to find the root of your joint pain, says Dr. Lewandowski. “It’s important to find a care provider you trust, who can be an ally with you and work with you to understand what your symptoms are and how to best manage them,” she says.

Keep Reading

Subscribe to CreakyJoints

Get the latest arthritis news in your inbox. Sign up for CreakyJoints and hear about the latest research updates and medical news that could affect you.